Raising Lazarus from the dead points to something crucial and way beyond the salvation of only one dead man and his two sisters.

Raising Lazarus was the final public action of Jesus—at least according to the unknown, anonymous author we call “John” in his theologically constructed narrative. So then, according to Johannine thought, the very last public thing Jesus did was restore life to a beloved friend. This final sign spoke volumes to the Johannine Jesus group. Consequently, the story granted to them an awareness about reversals, life springing from the grave, joy of reunification emerging from the separation death brings.

Here again is a shorthand overview of the story and its significance:

Raising Positive and Negative Shame

Although unseen by many 21st century Western Bible readers, concerns for honor and shame very much on display everywhere in Scripture. And they most definitely are at work in this Gospel story. Therefore, cultural insights from John Pilch and other Context Group scholars are of great assistance here.

Despite sounding strange to American ears, in the Mediterranean world of the Bible, having shame is good! Having a sense of shame (i.e., concern for group honor) signifies that you are civilized and that you are committed to your community and its needs. To have shame means to not be shameless—therefore, shame in this sense is positive. It indicates your emotions are under control, you won’t blow your top and derail social relations into a blood feud (“game over” in the Middle East).

But in the cultural world of the Scriptures, being shamed is terrible. To be dishonored (or shamed) is a deadly circumstance. Life at all levels of civilized society disintegrates when people are shamed. Shame in this negative sense happens when others refuse to acknowledge or deny someone’s honor claim. For instance, a Middle Eastern family is shamed when, throwing a wedding, their neighbors and friends fail to help provide more wine when it runs out (sound familiar, John 2:1-12). Another example would be when your beloved friends don’t show up at your time of need, or afterward, at your burial—that’s awfully shameful.

To Be Shamed is Worse than Death!

Lazarus rotting in his tomb is shamed, dishonored—this Beloved Disciple (don’t think John son of Zebedee) is abandoned by Jesus and his fellow followers in his darkest hour? And he is not the only one needing salvation from the shame of death! His sisters Mary and Martha equally need salvation from the sanction of shame. Apparently with no surviving parents, these Judaean sisters, with brother dead, just lost any voice they could have and their social security besides!

Raising Up a Well Known Johannine Story

It is interesting that the author we call “John” expected his audience to be familiar with this story. Read carefully John 11:2—

Mary was the one who had anointed the Lord with perfumed oil and dried his feet with her hair; it was her brother Lazarus who was ill.

See? It’s as if the audience would respond, “O yeah! Mary of Bethany! But that’s just it: we haven’t yet reached the story where Mary shines (John 12:1-7). And notice how, just as with Mary, no introductions are provided for either her sister Martha or Lazarus (after God and Jesus, the most important character in this Gospel—John 1:35-40; 11:3-5; 13:23-25; 18:15-16; 19:25-27; 20:2-10; 21:7; 21:20-24). This indicates that the audience knows their stories already, and well. As with every Gospel story, what we are getting here is an updated telling of what is already, by the time of the composition of “John,” an old familiar story.

So many times “John” presupposes that his audience is quite familiar with the story of Jesus. Clearly the document we call “John” was not written for outsiders who are unfamiliar with Jesus. Instead, like all the New Testament documents, this Gospel was written for insiders well-associated with the tradition. Consequently, any idea that this community would write out copies of “John” to hand out to strangers on the street is ludicrous.

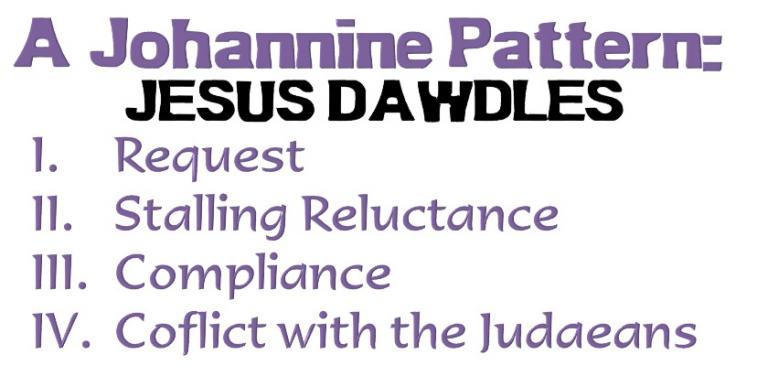

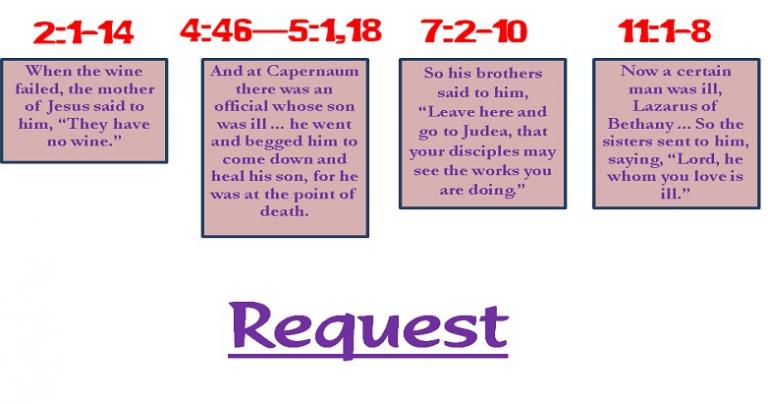

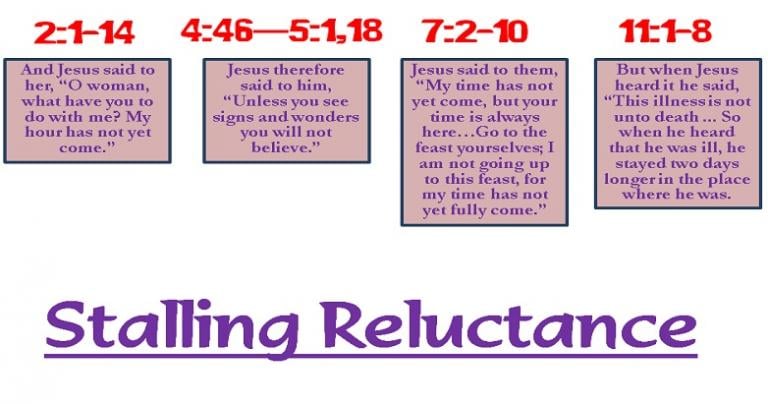

Raising the Uncomfortable Topic—Johannine Jesus Dawdles!

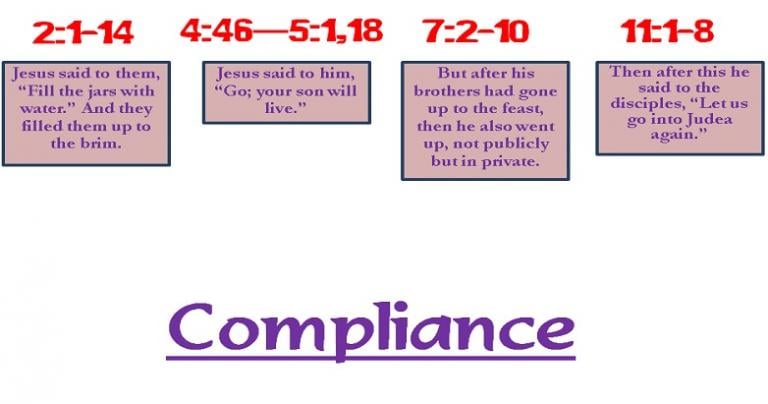

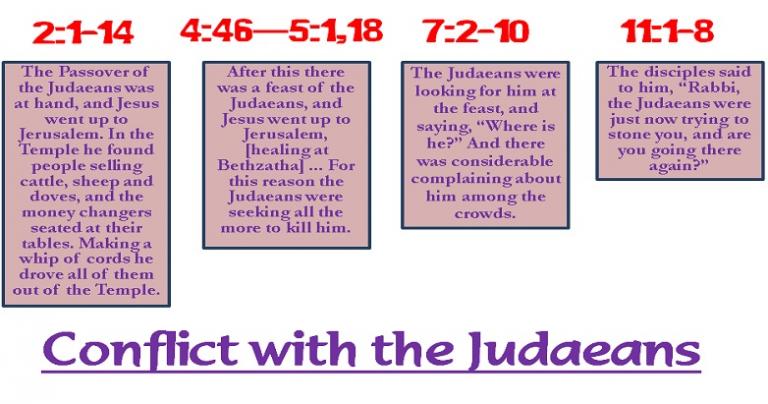

The Johannine Jesus tends to waste time while people get desperate. He dawdles. This leads to a repeated pattern in the Fourth Gospel. Here we see the pattern again. It starts with a request (John 11:1-3), then comes a mindboggling reluctance and dawdling from Jesus (11:4-6), and finally, he complies and helps (11:7-8). Check out the pattern below:

Again things are desperately bad for the two women who appear unmarried, Mary and Martha. Lazarus, likely an unmarried younger man (possibly a teenager? See video “How Healthy was Jesus?” below), likely their younger sibling, was probably their only male support. That the folk healer Jesus dawdles when his most attached disciples and sisters suffer greatly, and even miss the funeral, would seem like a slap of shame. Therefore, it would feel like being spit on. Is that testiness in Martha’s voice (John 11:21)?

Boy the Johannine Jesus sure seems to take his sweet time arriving at this tiny village on the southeastern slope on the Mount of Olives!

Just as the Johannine Jesus spoke with the Samaritan Woman contrasting ordinary well water with living water (John 4:7-15), so now he speaks with the Bethany sisters contrasting ordinary life with living life. But does Jesus have deep attachment for this family or not? If so, why the seemingly careless, nonchalant delay?

Raising Reasons for Stalling

According to Context Scholars Richard Rohrbaugh and Bruce Malina, “John” provides three reasons for Jesus’ dawdling in his narrative. First, it showcases Jesus is able to defeat death after three days—that’s why he arrives on the fourth day, John 11:17, 39. Second, Israelite symbolism associates the third day with the saving God’s glory or honor being manifested (Genesis 22:1-4; Exodus 19:10-11; Jonah 2:1). Third, as with every other New Testament interpretation of Jesus, the Johannine Jesus is all about honoring the Patron God of Israel.

But the Johannine Jesus gains honor also. Indeed, Rohrbaugh and Malina remind us that Jesus’ three days in the grave is anticipated by his three-day delay in rescuing Lazarus and his sisters from shameful death. The honor or glory of the Patron, God, is shared by the Son, or broker, even if only in a derivative way. The honor of God is a central theme of the Fourth Gospel (John 1:14).

Raising Understanding Among the Dimwitted Disciples

With the best and most attached disciple dead in his tomb, the others are helplessly bewildered as to why Jesus would endanger the whole movement by going back to Judea (John 11:7-16). They mention that the Judaeans were just trying to stone Jesus a little while back (cf. John 10:33, 39), and now Jesus is all gung-ho to return (John 11:8)?

Rohrbaugh and Malina remind us that before it acquired two thousand years of theological freight, “blasphemy” meant shaming someone by speech. For Jesus, the peasant artisan, to claim to be “Son of God”—whether meaning shamanic folk healer/holy man or something greater (cf. John 1:1-18)—was considered blasphemy by Judaean elites.

Suicide Mission?

Could Jesus be planning a suicide mission? Middle Eastern faction leaders have been known to do that from time to time. The Middle Eastern disciple Thomas Didymus, probably a teenager, thinks so, and like a typical Mediterranean macho male says as much (John 11:16). Think of a young impressionable Middle Eastern male going on a suicide mission when you read these verses. Yet again these youngsters miss the mark.

Notice how Jesus calls Lazarus “our friend” (John 11:11)? Rohrbaugh and Malina explain that the Johannine Jesus extends this special relationship to all his innermost circle of followers (cf. John 15:14-17). Unlike the Synoptic Gospels, in “John” there was a disciple named Lazarus who sat in the innermost circle of Jesus followers. “Friend” in this Mediterranean social context means intense loyalty shared among social equals. In the Fourth Gospel, the Beloved Disciple Lazarus is ranked the most insider of all insiders. And he is the greatest among followers also, at least until the appended chapter 21 (vv. 15-23).

Raising All Sorts of Problems

The unknown, anonymous author we call “John” stresses how close the story is from the most loathed location as far as the Johannine antisociety was concerned—the Temple-city, Jerusalem (John 11:18). Death-imagery is lathered on thick by “John.” For an ancient Israelite funeral, you could never have too many mourners. The more impressive the gathering of mourners meant the greater the family’s honor.

Unlike the United States where death is seen puncticular, happening at the exact moment of brain-death, death was interpreted as a year-long process by ancient Israel. In this fiercely gender-divided world, men and women would process to the grave site separately, and after, return home separately. Then the women would commence with a thirty-day period of mourning. To do this, they would mourn seated on the floor.

Recalling Symbolism

Last time, we gave a shorthand explanation of the deep meaning behind the exchange of Jesus and Martha and how Martha was a rich symbol for the Johannine Jesus group. It is somewhat odd that Martha, a grieving woman and likely the younger sister, exits her village Bethany to meet Jesus outside (John 11:20-31). At first, her words betray that she is not yet a full insider with Jesus (John 11:24)—she confesses as would an Israelite of the sect of scribal Pharisaism. But soon she changes, joining Jesus’ core group (John 11:27). She eventually comes to understand the Johannine anti-language and its group loyalty.

Why is the Johannine Jesus himself “the resurrection and the life” (John 11:25-26)? It is because whosoever lives currently (sometime ca. 100 CE) inside the Johannine Jesus group and believes that Jesus is God’s Sky Vault Man broker will never die. The Literal Sense of the antilanguage expression “believe into Jesus” (John 3:16) means to forever interpersonally bond with the Johannine ingroup and antisociety. Thus, John 11:25-27 articulates a central motivation to stick with the Johannine community.

Raising Mary and the Subject of Emotions

In the following story (John 12:1-8), Mary of Bethany seems to be able to dispose her family’s wealth with ease. Scholars Rohrbaugh and Malina think this therefore indicates that Mary is the elder sister. Initially she remains in the house like the older sister would accompanied with other female mourners (John 11:31). But eventually, like her younger sister, Mary also ventures outside their village to meet Jesus (John 11:32-34). Why?

Like the younger Martha, Mary also acknowledges Jesus as an Israelite shamanic folk healer (John 11:32), but nothing more (John 1:1-18). It might seem, to Western eyes anyway, that she is displeased (and perhaps pissed off?) at Jesus the dawdler. We might speculate along these lines reasonably at least because of her public display. See how Mary drops to the ground before him in an outburst? This could be respectfully interpreted as cunning. Could she be reminding onlookers of Jesus’ failure to arrive on time? Women to this day are the intelligentsia of Middle Eastern villages.

However, whenever a Western exegete (say like Francis Moloney or N. T. Wright) or theologian comments on the emotional reaction of Jesus here, or any other character’s emotions, take it with a grain of salt. Unfortunately, Western readers, even brilliant, learned scholars like these two, are infected by spurious familiarity and the fallacy of “Immaculate Perception” (“there can be no doubt…” as Wright over-confidently says of Jesus weeping, John 11:35). Cultural anthropologists repeat to deaf ears that the only thing transcultural about human emotion is the sensory experience. Besides that? ZILCH.

So what if an emotional expression by some Mediterranean biblical character looks similar to something we introspective Western 21st century people experience? Guaranteed these expressions are markedly different, and all the sentimental desire in the world to force-fit “Jesus wept” (John 11:35) and why Jesus was “perturbed” (John 11:33, 38) into your ethnocentric, culturally-congenial box simply cannot correspond with reality. As far as their ethnocentric, psychological and introspective understandings of Jesus’ emotions here are concerned, Wright is wrong and Moloney is baloney.

Raising a Respectful Reading of Emotions

If we should read the text with cultural sensitivity as Rohrbaugh, Malina, and their Context Group friends highly recommend, it could very well be that Jesus was “perturbed” or “deeply disturbed” means that Jesus displayed indignation and chagrin. Why? Perhaps because he was publicly embarrassed by when Mary publicly challenged him (John 11:32).

Consider all the mourners are present. Consider her entourage accompanying her. And consider Jesus’ company of his other disciples. Will he treat them as callously and carelessly as he did Lazarus and his sisters? This is humiliating. Embarrassing!

It is culturally plausible, in any case, that Mary’s display would provoke questions from the onlookers (John 11:37). How could this dawdler be a true friend? Here is Jesus irritated and uninvolved, surrounded by many weepers. It’s likely what’s being described here is the Johannine Jesus getting indignant.

Raising Lazarus

Great tension mounts due to Jesus having dawdled around (John 11:6, 17) and the extreme displeasure of the mourners (John 11:32, 37). Will Jesus rescue Lazarus (and the sisters)? That’s ultimately why he journeyed back to Judea, to Bethany (John 11:11).

Taking away the stone (John 11:39, 41) and removing the bandages (John 11:44) from the Beloved Disciple (John 11:36) the very symbol of the Johannine Jesus group, is an outward display of God’s honor (John 11:40). It also publicly demonstrates that Jesus is indeed God’s broker, the Sky Vault Man or bridge between sky vault and “the world” (John 1:50-51). Because of this, many Judaeans believe into Jesus (John 11:45)—thus detaching themselves from “the world” (i.e., the dominant Israelite society) by embedding themselves into the Johannine antisociety.

Conclusion

As explained in the video from Sunday’s post, all this would be very encouraging to a grieving Johannine Jesus group living decades later. Despite the resurrection of King Jesus, believers kept dying. But this updated story reminded Johannine believers that “believing into Jesus” demands trust in never dying (John 12:26). Such interpersonal relationship with Jesus the Sky Vault Man inside the Johannine Jesus group was recognized as truly undying. Belong to the Johannine Jesus group and you will see the glory of God.

Through the experience of this ancient Jesus group, Jesus the Word of God speaks to us all today. Even in the darkness of uncertainty of pandemics and economic disasters, our bond with the Lord is undying.