Our model for describing Revelation and Mark 13 is fundamentally flawed.

Around this time of year, Catholics get exposed to the apocalyptic and eschatology. For instance, this Sunday, many Catholics will hear about the apocalyptic preacher, John the Baptist. They will be told how John prepared the way for the Messiah, someone expected to arrive in the Last Days for everyone, not only for Israelites. Last Sunday’s Gospel was Mark 13, the so-called “Synoptic Apocalypse,” an expression we debunked in my last post.

Eschatology means the study of the last things. Does the Bible do that? “Last things” is a vague expression. Last things about what? Whose “last things”?

Model Definitions

Biblically, “apocalyptic” refers to a genre of revelatory literature worked into a narrative. John J. Collins explains that in apocalyptic literature, “revelation is mediated by an otherworldly being to a human recipient, disclosing a transcendent reality that is both temporal, insofar as it envisages eschatological salvation, and spatial, insofar as it involved another, supernatural world” (see his “Apocalypse: The Morphology of a Genre”).

Excellent definition, Collins. The only problem is that biblical people were clueless about all that stuff. Thus they didn’t know “other worlds” and anything “otherworldly.” And they couldn’t distinguish “supernatural” from “natural.” Also, they weren’t aware of any “transcendent realities,” “eschatological salvation,” or future as we understand time. So if you can look past those tiny problems, then I guess you have a great model by which to read Mark 13 and Revelation.

NOT. Watch the video to get why.

Adequate Terms?

When using terms like “apocalyptic” and “eschatology” to describe first-century realities and literature, we should ask how adequate are these terms? By this, I mean, how respectful are our mental scenarios and models concerning New Testament people and writings? Are they up to the task of describing things accurately and provide for us a bridge of understanding? Or do they instead distort matters and cause misunderstanding?

Even though it looks a lot like the Greek apocalypsis (emic—see below), our term apocalyptic (failed etic—see below), as used in today’s theological schemas, is inadequate at describing first-century scenarios. Therefore it fails to explain what’s going on in Mark 13 and the book of Revelation. We need better terms—like “astral prophecy.”

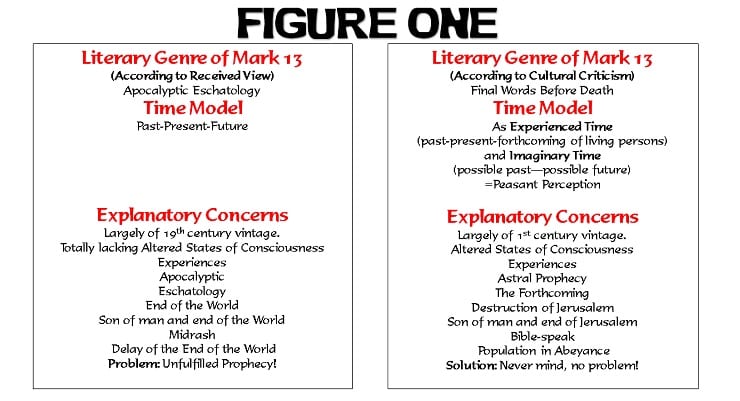

Check out this chart. It contrasts the received view of Mark 13 with a culturally-informed model.

Making the Model: Etic VS Emic

Back in Eastertide, we talked about the relationship between two exceptional terms, emic (e.g., “I was in spirit…”) and etic (e.g., “fell into a trance”). These useful words were introduced by anthropologist K. L. Pike. They help us escape from believing we have achieved immaculate perception in reading biblical documents.

Native speakers, whether John the Seer (Revelation 1:9) or Jesus or “Mark” (Mark 13), take their own social system for granted. Therefore, they use language, presuming that everyone interacting with them understands “how the world works” as they do. Consequently, when describing events and behavior, they do so from their own native point of view. This is called emic description (from phonemic). Mark 13, Revelation, and the entire New Testament is a treasury of emic data.

Consider 21st-century Western Christians, all outsiders to the ancient Mediterranean cultural world of the Bible, reading Mark 13 or Revelation. What should they do? Invariably, they will develop some model of how the world works that they imagine, including both the world of the observer (theirs) and the world of the observed.

Hopefully, they will do it in some articulate, non-impressionistic, and independently-verifiable fashion when they do. Accomplishing this creates an adequate model for understanding the ancient document in question, one that will provide them with etic descriptions (from phonetic).

The Right Model

Whether they know it or not, every Western Bible reader produces a model, making etic descriptions. The question is: are these descriptions adequate, or are they flawed?

Paraphrasing Dr. Bruce Malina, to articulate the emic in the etic is to bridge cultures so as to effectively comprehend the biblical text in question. This happens because your model helps you respectfully read. Consequently, you overcome a “hermeneutical gap” between the New Testament world and our 21st-century Western society. Understanding results.

When it comes to “apocalyptic” and “eschatology,” the $1 million question remains: Is our etic adequate? Is our etic honest or dishonest to the emic?

“Apocalyptic” and “eschatology,” despite their popularity among scholars, simply reflect a failed model. Hence, these terms cannot respectfully convey the emic of Mark 13 and the book called Revelation. Ultimately, they belong to a flawed etic.

A Helpful Etic

What would be a healthy etic that establishes a bridge of understanding? In Mark 13, we see prescient (via an altered state of consciousness) final words of an Israelite facing death (Jesus) given in astral prophecy “biblespeak.” Hence, with this healthy etic description, we have laid out a bridge of understanding. Now, we can grasp what’s going on.

As you should be able to see, emic and etic present two different viewpoints to understand human behavior. While our etic view is necessarily outside the system, we attempt to navigate, biblical characters’ and authors’ emic view is native to the system we observe. In other words, their descriptions are congenial to the social structure of the ancient Mediterranean. But their emic model is strange and foreign to us! Therefore, unless we make a happy marriage between emic and etic, forget understanding the Gospels or any other Scripture.

Any Bible reader from our 21st-century Western world attempts cross-cultural communication every sing time they pick up a Bible to read. Just the same, we have to read the Scriptures first from our own cultural world. This is because no other beginning is possible. It follows why comparative anthropological disciplines are essential to Scripture study. In other words, without culturally-informed historical-critical tools and models, you might as well try to read the Bible blindfolded.

German Baggage

What happens whenever we neglect this comparative approach? This results in us polluting our Bible-reading. Ultimately, this will distort the Scriptures.

The 19th-century Germans who came up with the etic terms “apocalyptic” and “eschatology” to read Mark 13 and Revelation produced a failed etic. Because of their baggage, we attempt to read these works through murky waters.

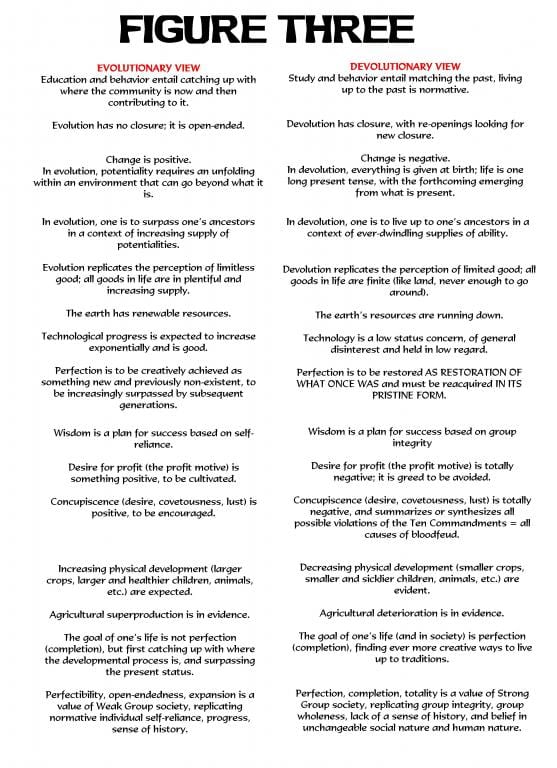

The watershed event of the Industrial Revolution gave the German theologians, as it did our culture today, a story of ongoing progress. Things keep getting better in a never-ending ascension toward the newer, brighter tomorrow. Since we all got sold on this continuous betterment evolutionary idea, it impacts our perception of reality. We’d be kidding ourselves if we thought this baggage didn’t color our Scripture-reading.

Evolution VS Devolution

But look at the chart here. First-century people were not like 19th-century German theologians or us Western Christians living today. As Malina and John Pilch show, they believed in devolution. Both society and the cosmos were running down.

The story accepted by everyone was that people everywhere were becoming weaker and more wicked (Jubilees 23:13-15; Matthew 24:5-12; 2 Timothy 3:1-5; 2 Esdras 6:24; and 2 Baruch 48:32-38). This devolutionary perspective can be found in later prominent Church writers, such as Cyprian (To Demetrius 3, 20, 23) and Ambrose (Death as Good 10.46). This belongs to a very different model than that used by many Western theologians.

Better Model, Better Descriptions

How do the etic descriptions “apocalyptic” and “eschatology” fare against the ancient Mediterranean devolution perspective? They fail to bridge the gap. Therefore, Malina and Pilch provide a culturally-informed etic description—”kakoterology” (= worse-ology). This is up to the task of bridging understanding between our culture and the ancients’.

And what about describing our 21st-century Western worldview of ongoing evolution and progress? Malina and Pilch suggest we would be more honest to use “kreittology” or “kreissology” (meaning better-ology) to describe the way we view things.

Finally, Malina points out something fascinating concerning Mark 13, Revelation, and the entirety of the New Testament. Malina explains that although prevalent everywhere in the ancient Mediterranean, New Testament writings fail to highlight the common devolutionary perspective.

Instead, very true to standard present-oriented peasant views, these documents concentrate on what is about to transpire, what is coming up “next” or “soon.” Therefore, Malina and Pilch provide the superior etic descriptions “proximatology” or “nextology” to really understand what’s going on in Mark 13 and Revelation.