Yes, I wonder about that question too. 🙂

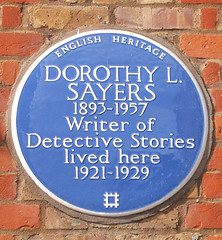

One of the most famous musings on the subject was written by Dorothy L. Sayers–better known to many of us as the author of the Lord Peter Wimsey series of detective novels–over seventy years ago, in 1942. She wrote in a different time and place–wartime Britain, full of deprivations and ration coupons, before today’s era of interconnected technologies and ever-changing vocational landscapes. But her words still echo down the decades:

If we do not deal with this question now, while we have time to think about it, then the whirligig of wasteful production and wasteful consumption will start again and will again end in war. And the driving power of labor will be thrusting to turn the wheels, because it is to the financial interest of labor to keep the whirligig going faster and faster till the inevitable catastrophe comes.

And, so that those wheels may turn, the consumer – that is, you and I, including the workers, who are consumers also – will again be urged to consume and waste; and unless we change our attitude – or rather unless we keep hold of the new attitude forced upon us by the logic of war – we shall again be bamboozled by our vanity, indolence, and greed into keeping the squirrel cage of wasteful economy turning. We could – you and I – bring the whole fantastic economy of profitable waste down to the ground overnight, without legislation and without revolution, merely by refusing to cooperate with it. I say,

we could – as a matter of fact, we have; or rather, it has been done for us. If we do not want to rise up again after the war, we can prevent it – simply by preserving the wartime habit of valuing work instead of money. The point is: do we want to?….Whatever we do, we shall be faced with grave difficulties. That cannot be disguised. But it will make a great difference to the result if we are genuinely aiming at a real change in economic thinking. And by that I mean a radical change from top to bottom – a new system; not a mere adjustment of the old system to favor a different set of people.

The habit of thinking about work as something one does to make money is so ingrained in us that we can scarcely imagine what a revolutionary change it would be to think about it instead in terms of the work done. To do so would mean taking the attitude of mind we reserve for our unpaid work – our hobbies, our leisure interests, the things we make and do for pleasure – and making that the standard of all our judgments about things and people. We should ask of an enterprise, not “will it pay?” but “is it good?”; of a man, not “what does he make?” but “what is his work worth?”; of goods, not “Can we induce people to buy them?” but “are they useful things well made?”; of employment, not “how much a week?” but “will it exercise my faculties to the utmost?” And shareholders in – let us say – brewing companies, would astonish the directorate by arising at shareholders’ meeting and demanding to know, not merely where the profits go or what dividends are to be paid, not even merely whether the workers’ wages are sufficient and the conditions of labor satisfactory, but loudly and with a proper sense of personal responsibility: “What goes into the beer?”

****

…. I am persuaded that the reason why the Churches are in so much difficulty about giving a lead in the economic sphere is because they are trying to fit a Christian standard of economic to a wholly false and pagan understanding of work.

What is the Christian understanding of work? …. I should like to put before you two or three propositions arising out of the doctrinal position which I stated at the beginning: namely, that work is the natural exercise and function of man – the creature who is made in the image of his Creator. You will find that any of them if given in effect everyday practice, is so revolutionary ( as compared with the habits of thinking into which we have fallen), as to make all political revolutions look like conformity.

The first, stated quite briefly, is that work is not, primarily, a thing one does to live, but the thing one lives to do. It is, or it should be, the full expression of the worker’s faculties, the thing in which he finds spiritual, mental and bodily satisfaction, and the medium in which he offers himself to God.

Now the consequences of this are not merely that the work should be performed under decent living and working conditions. That is a point we have begun to grasp, and it a perfectly sound point. But we have tended to concentrate on it to the exclusion of other considerations far more revolutionary. ….

This first proposition chiefly concerns the worker as such. My second proposition directly concerns Christians as such, and it is this. It is the business of the Church to recognize that the secular vocation, as such, is sacred. Christian people, and particularly perhaps the Christian clergy, must get it firmly into their heads that when

a man or woman is called to a particular job of secular work, that is as true a vocation as though he or she were called to specifically religious work. The Church must concern Herself not only with such questions as the just price and proper working conditions: She must concern Herself with seeing that work itself is such as a human

being can perform without degradation – that no one is required by economic or any other considerations to devote himself to work that is contemptible, soul destroying, or harmful. It is not right for Her to acquiesce in the notion that a man’s life is divided into the time he spends on his work and the time he spends in serving God. He must be able to serve God in his work, and the work itself must be accepted and respected as the medium of divine creation.In nothing has the Church so lost Her hold on reality as in Her failure to understand and respect the secular vocation. She has allowed work and religion to become separate departments, and is astonished to find that, as result, the secular work of the world is turned to purely selfish and destructive ends, and that the greater part of the world’s intelligent workers have become irreligious, or at least, uninterested in religion.

But is it astonishing? How can any one remain interested in a religion which seems to have no concern with nine-tenths of his life? The Church’s approach to an intelligent carpenter is usually confined to exhorting him not to be drunk and disorderly in his leisure hours, and to come to church on Sundays. What the Church should be telling him is this: that the very first demand that his religion makes upon him is that he should make good tables.

Church by all means, and decent forms of amusement, certainly – but what use is all that if in the very center of his life and occupation he is insulting God with bad carpentry? No crooked table legs or ill-fitting drawers ever, I dare swear, came out of the carpenter’s shop at Nazareth. Nor, if they did, could anyone believe that they were made by the same hand that made Heaven and earth. No piety in the worker will compensate for work that is not true to itself; for any work that is untrue to its own technique is a living lie.

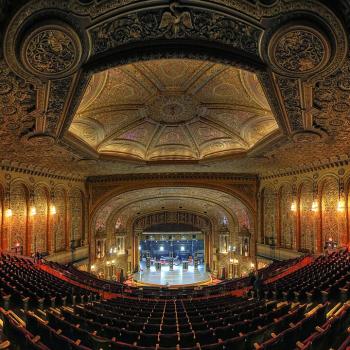

Yet in Her own buildings, in Her own ecclesiastical art and music, in Her hymns and prayers, in Her sermons and in Her little books of devotion, the Church will tolerate or permit a pious intention to excuse so ugly, so pretentious, so tawdry and twaddling, so insincere and insipid, so bad as to shock and horrify any decent draftsman.

And why? Simply because She has lost all sense of the fact that the living and eternal truth is expressed in work only so far as that work is true in itself, to itself, to the standards of its own technique. She has forgotten that the secular vocation is sacred. Forgotten that a building must be good architecture before it can be a good church;

that a painting must be well painted before it can be a good sacred picture; that work must be good work before it can call itself God’s work.Let the Church remember this: that every maker and worker is called to serve God in his profession or trade – not outside it. The Apostles complained rightly when they said it was not meet they should leave the word of God and serve tables; their vocation was to preach the word. But the person whose vocation it is to prepare the

meals beautifully might with equal justice protest: It is not meet for us to leave the service of our tables to preach the word.****

This brings me to my third proposition; and this may sound to you the most revolutionary of all. It is this: the worker’s first duty is to serve the work. The popular catchphrase of today is that it is everybody’s duty to serve the community, but there is a catch in it. It is the old catch about the two great commandments. “Love God – and your neighbor: on those two commandments hang all the Law and the Prophets.”

The catch in it, which nowadays the world has largely forgotten, is that the second commandment depends upon the first, and that without the first, it is a delusion and a snare. Much of our present trouble and disillusionment have come from putting the second commandment before the first…..

The only true way of serving the community is to be truly in sympathy with the community, to be oneself part of the community and then to serve the work without giving the community another thought. Then the work will endure, because it will be true to itself. It is the work that serves the community; the business of the worker is to serve the work.

You can read the entire essay here. What do you think? Do you agree with Sayers’ three propositions? Do you think they are still relevant today? Let us know! (And stay tuned for an occasional feature of great thoughts on work and vocation from great Christians in this space.)

You can read the entire essay here. What do you think? Do you agree with Sayers’ three propositions? Do you think they are still relevant today? Let us know! (And stay tuned for an occasional feature of great thoughts on work and vocation from great Christians in this space.)

Images: “God and Mammon” by Gilly Walker, “Table and Bench” by Kate Gardiner, “Dorothy L. Sayers” by Christian Lüts