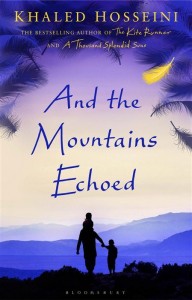

Like Khaled Hosseini’s two earlier novels, The Kite Runner (2003) and A Thousand Splendid Suns (2007), which spent a combined total of 171 weeks on the bestseller list, his latest novel, And the Mountains Echoed has received wide acclaim, and has been described as “heartbreaking,” “emotionally resonant,” and the writer’s “most ambitious work yet.”

While reading, I often felt that I wanted the novel to have a smaller cast, only because some of the characters struck me as so much more interesting than others: for example, the story of the children’s stepmother Parwana and her disabled twin sister Massoma, or the Afghan-American cousins Idris and Timur who return to visit war-ravaged Kabul, where the used car salesman Timur makes deals while the doctor Idris finds it difficult to cope with the burden of guilt he feels at the sight of suffering he has been spared from. I wanted to read more about them – and less about some of the others. The chapter narrated by the Greek doctor Markos in a long flashback, which tells of his friendship with Thalia, a girl disfigured after being bitten by a dog, seems to be inserted solely to explain why Markos chose to be a plastic surgeon and make his way to Afghanistan. It’s a well-written section of the book, but seems to be included for not entirely justifiable reasons, simply adding further complexity to the already complex, multi-stranded plot.

This part of the novel unfolds on the Greek island of Tinos, while other parts of the novel are set in Paris and San Francisco, ranging far beyond the small village of Shadbagh, where the novel opens. Hosseini himself has described the novel as more global and “less Afghan centric“ than his previous books. Although the characters are all impacted by the events in Afghanistan, the history of the country is less central to this novel, which is more about family, love between siblings, and childhood. The title of the novel is an indication of this, a twist on a line from a William Blake poem, called “Nurse’s Song (Innocence).” Hosseini describes being inspired by the line “And all the hills echoed,” after listening to Allen Ginsberg singing the poem.

But despite this book being less “Afghan-centric” than his previous works, one of the focuses of the reviews has been “what it means to be an Afghan woman.” The novel does feature a number of Afghan women characters from Parwana and Masooma, to the two women named Pari, and most particularly, Nila Wahdati, a complicated character seen in one review as one of the writer’s “most compelling creations,” and a character Hosseini describes as arising from the memories he has of the parties his parents threw in the Kabul of the 70s:

“There would be really striking women in short skirts. Beautiful, very outspoken, temperamental, endlessly – in my young mind – interesting. Drinking freely, smoking. Nila is a creation from my memory of that kind of woman from that time and that place.”

For many reviewers, there seems to be a disjuncture between this image of a woman who belongs a particular time and place (the Westernizing middle class in Kabul in the 70s) and the words “Afghan woman.” The disjuncture is for me no more apparent than in this article, which has an image of women visiting a record store in Kabul in the 1950s or early 60’s but goes on to connect the French-Afghan middle-class-privileged Nila Wahdati to the folk literature of the landai, two-line folk poems that are often cast in the voice of women. The writer of the article does strive valiantly to connect the two by referring to “the centuries-long, ongoing struggle of Afghanistan’s female poets, who have enjoyed eras of flourishing freedom of expression and endured eras of forced secrecy.” But thiscomes off more as an attempt to find some “authenticity,” some real Afghan roots for this “modern” character who doesn’t fit the set parameters of “Afghan woman.”

As Andrea Mitchell, interviewing the writer, noted of the character:

“She’s very surprising to people who have a conception of Afghan women and how…repressed they’ve been legally, and politically and physically because she is such a modern woman.”

Earlier in the interview, Mitchell speaks of the fragility of the legal rights women have won in Afghanistan, and Hosseini is careful to point out that “things for women in Afghanistan have improved in pockets,” and that there are many rural areas where very little has changed since the days of the Taliban government, although in the urban centres there have been strides in the direction of women’s equality. The differences of urbanization and class distinctions that Hosseini hints at, however, are flattened by Mitchell’s rather remarkable final question: “if you had been a girl of your generation would you have had the education and the opportunities?”

Underlying the question is the assumption that that there can only be one possible life for an Afghan woman of a particular generation, a statement that sweepingly negates all distinctions of class, ethnicity, profession, geography.

Unlike many of the reviewers of this novel, I enjoyed reading And the Mountains Echoed far more than The Kite Runner. I found it less contrived, more compelling, and full of a sense of warmth and understanding for many of the characters, especially the morally ambiguous, very flawed ones. This is a novel that some (not me) may find a little too saccharine and sentimental in places, but that does “move people,” as Hosseini says he wanted it to. I suspect it won’t, however (despite the “modern” Nila Wahdati), do much to move people’s preconceptions about what an “Afghan woman” is or can be. But perhaps that is too much to ask of a novel.