Originally published here. Where does parody end and self-exoticization begin? At what point does the Arab woman artist, stepping into the so-often imagined space of “The Harem” risk pandering to an audience that seems to have a never-ending appetite for remediations of Orientalist artwork? Lebanese photographer Rania Matar’s wonderful and insightful A Girl in Her Room series (capturing teenage girls in their most sacred space, the bedroom) includes some photographs that are clearly posed to mimic familiar odalisque imagery:

Was the subject asked to pose this way? Is the audience being invited to share a joke with the subject, or at the expense of the subject? Or is it simply playful? Photographing girls from the Middle East and girls from the US, Matar says that she “became fascinated with the similar issues girls at that age face, regardless of culture, religion and background.”

I was discovering a person on the cusp on becoming an adult, but desperately holding on to the child she barely outgrew…Posters of rock stars, political leaders or top models were displayed above a bed covered with stuffed animals…photos, clothes everywhere, chaotic jumbles of pink and black make-up and just stuff, seemed to give a sense of security and warmth to the room

This description of chaotic jumble and abundance is visible many of the images from the US – and in some of the images from the Middle East. But what about the stripped down rooms of the refugee camps?

And where in this girl-becoming-woman does the odalisque pose come in? And how should we read the image of the girl holding the pink scarf up to cover everything but her kohl-lined eyes?

And where in this girl-becoming-woman does the odalisque pose come in? And how should we read the image of the girl holding the pink scarf up to cover everything but her kohl-lined eyes?

According to popular belief, all Arab women can be divided into twocategories. Either they are shadowy nonentities, swathed in black from head to foot, or they are belly dancers – seductive, provocative, and privy to exotic secrets of lovemaking. The two images, of course, are finally identical, adding up to a statement that all Arab women are, in one sense or another, men’s instruments or slaves.

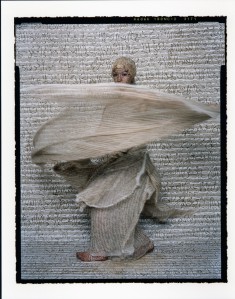

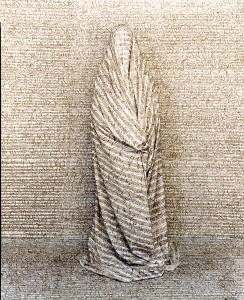

Arab women artists who explore the veil must deal with these two images – as Moroccan Lalla Essaydi’s work does with her veil-dancers and her fully covered women.

Essaydi has produced some sumptous, beautiful images that reproduce the harem and that draw you in to this imagined private women’s world – but to say what? In a Jadaliyya interview of Essaydi, the artist responds to this question directly, arguing that she is “not “reproducing” the “exotic” and “mysterious” depictions of Arab women from Orientalist harem art” but “deconstructing these paintings by using the same stereotypes one finds in these paintings.”

The inclusion of calligraphy in many of Essaydi’s works allows the artist to intervene directly; as she puts it, “the interplay between graphic symbolism and literal meaning, as well as the European assumption that the written holds the best access to reality, are constantly questioned.”

Essaydi’s interventions in the harem discourse recall Assia Djebar’s ‘interventions’ in Femmes d’Algers dans leur appartement, (“Women of Algiers in Their Apartment”). In this text, Djebar analyses (and according to some, appreciates) the paintings of Delacroix and Picasso, and their works (both entitled “Femmes d’Alger dans leur appartement”).

Much has been written about Djebar’s work, and how “Djebar takes the (supposedly) historical portrayal of Delacroix’s harem of women, and pushes it forward through the struggle for independence and into the post-independence era” – whereby the harem is stripped from its seductive icolography to the restricted space of prisons and mental asylums.

Yawm min al-ayyam we just decided: Enough is enough / A unique opportunity, the Retrospective brought us all together / I looked across the gallery at Red Culottes and gave the signal / She passed it on to Woman in Veil and we kicked / through canvas / Most of us have very good legs – lower body strength, / you know / The Persian model needed help, but it wasn’t her, / it was the way she was drawn.

I forgot to be your every orientalist dream, genie in a bottle, belly dancer, harem girl, soft spoken arab woman

For me, the most powerful remediations of the harem are ones that connect the iconography of the harem-girl to broader struggles: Suheir Hammad does this: not your harem girl geisha doll banana picker pom pom girl pum pum shorts coffee maker town whore belly dancer private dancer la malinche venus hottentot laundry girl So does Pauline Kaldas, in her poem “Exotic” (1994):

Some will say, come on, this was all a long time ago. Mattisse and Delacroix and even Picasso – this is old news. Get over it. But type veil and harem into google images today and you will come up with a never-ending proliferation of harem girl halloween and belly dancer costumes (likewise, geisha girls costumes are prevalent). Should Arab women artists ignore this and seek their material elsewhere, or should they continue to risk and (sometimes fall into) pandering and self-exoticisation, as they work to answer and alter these images?