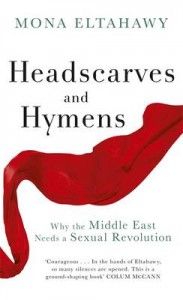

We will soon have a full review of Mona Eltahawy’s Headscarves and Hymens: Why the Middle East Needs a Sexual Revolution. In the meantime, here is a discussion on the book by three of our writers.

Sya: What’s up with books about “the Middle East and North Africa” that are about female genitals, one way or another?

Tasnim: The title reminded me of Shereen El Feki’s Sex and the Citadel. Having read both books, I feel Sex and the Citadel (reviewed here by Sya) was much better than Headscarves and Hymens for a variety of reasons – from Feki’s professional background in reproductive health to her historical contextualization of cultural attitudes about sex in the region. However, both titles go for the bold I’m-tackling-taboos-and-I-know-it attitude. With Feki’s book, the flair came from the wordplay; with Mona’s, it is the alliteration. As with Eltahawy’s now infamous 2012 Foreign policy article “Why do they hate us?” (with its painted on naked niqabi), which MMW reviewed in two parts,there’s a lot to wade through before we even get started on the content.

Of course, that sensationalist stuff is what is meant to grab the reader – so maybe we shouldn’t judge books by their covers. Or their titles. Or bristle at the flowing red across white that makes the parallel obvious (just in case the alliteration didn’t make it clear for you).

Shireen: I must confess that I started reading this book with a lot of bias. I had read very few reviews of the book, and if western journalists who were rooting for Mona weren’t fans of her book, there was no way I was going to be. I am not a fan of Ms. Eltahawy’s work. I find that some of her anti-niqab positions (which she refers to in the book on pages 60-75, and defends her position) on Muslim women’s dress reductive and unhelpful to the greater Muslimah community. But I attempted to put aside read her latest work without grinding my teeth excessively or hijabdesking.

Tasnim: So, what were your main issues with the book?

Sya: Eltahawy insists on blaming complex problems in “the Arab world” (i.e. from Morocco to Saudi Arabia) on the “toxic mix of culture and religion.” But blaming everything from street harassment to female genital mutilation (FGM) on “culture” is a dead-end argument: Why do Muslim/Islamist/Arab men harass women? Because they hate us. Why do they hate us (the headline of Eltahawy’s 2012 article and also the title of her first chapter)? Because they’re Muslim/Islamist/Arab, that’s why. This doesn’t help readers to understand the causes of these social phenomena.

Shireen: One particular review states that Eltahawy’s claims are “irrefutable”. I laughed.

Mona Eltawahy’s book was poised to be a manifesto of sorts. But a manifesto needs to backed up with empirical data, studies, reports or… something.

Her book is filled with personal anecdotes, and although her lived experience is legitimate, it is her story and not a call for a sexual revolution for every Muslim woman. And Ms. Eltahawy certainly does not speak for millions of women.

Tasnim: To be fair though, Eltahawy responds to this charge that she doesn’t speak for all Muslim women repeatedly, acknowledging that of course she doesn’t and that everyone has a voice. But she has pointed out that she feels responsible, as someone whose voice is heard more than many other Arab women, to use that platform she has to speak up about the misogyny in Arab culture. And I think that is not something we should just dismiss – the call for self-criticism, to step up and speak up, is something valuable.

In the context of acknowledging her own privilege and therefore her responsibility to speak up, it makes sense that she should use her own story to illustrate her argument for a social and sexual revolution in the Arab world.

Sya: Her personal experiences growing up in Jeddah and Cairo do give more insight into the motivations behind her political beliefs and her activism.

Shireen: Yes, and her experiences of being molested while performing hajj are upsetting to read and also similar to what many women face. It is horrible indeed. And she does tackle what are unfortunately all-too-common stereotypical tropes about Muslim women and clothing. Her reference to an incident in which she was lectured in Cairo metro by an aggressive face-veiling woman about a woman being a “wrapped candy” needing covering (p. 34) sounds more like she read some of MMW’s critiques of these messages.

The problem is, she uses misogynists’ comments and situations to back up her points in a selective manner throughout her book. Which is fine for a personal history but not when declaring that the book calls for action and outage on a societal level. Is the action and outrage to be selective as well? Is Mona attempting to incite rage from her female Muslim readers by providing them with a half-baked pseudo-manifesto? Muslim women reading this book are a lot smarter than that.

Tasnim: I agree; a more contextually grounded analysis of the problems would have been a better way to fulfil that responsibility Eltahawy has taken on – not in order to make the case for revolution (I think we all agree that change needs to happen) but to tackle the more difficult questions of what that revolution entails and how it is to be achieved. I think the balance between the anecdotes and personal stories on the one hand and the analysis and empirical data on the other is a little skewed.

Shireen: At one point, she references hijab as awkward or out-of-place even during her experience at Hajj as a teenager: “I looked like a nun in my white pilgrimage clothing” (p. 50). Or, um, she looked like every other Muslim at the Kaa’ba performing a required pillar of faith.

Sya: I think Eltahawy’s culture blaming is especially unimaginative because she does address issues of military and police brutality, and other forms of state-sanctioned misogyny.

Tasnim: You mentioned that she blamed the problems facing women in the Arab world on a “toxic mix of culture and religion.” Which begs the question: what about the political situation? How does that influence what is happening?

Shireen: Here’s a good example of glossing over anything that doesn’t fit the narrative: Mona insists that women in Cairo suffer abuse because they do not veil. But a mainstream women’s advocacy group in Egypt says that 99% of Egyptian women have faced constant street harassment and abuse – regardless of what they wear. One would assume that an activist so engulfed in the Arab Spring in Egypt would acknowledge this known fact – and not simply advocate for a specific group of women who are victimized. It is only much later in the book that she acknowledges this as she discusses the experiences of activists at Tahrir Square during the Arab Spring.

Tasnim: Ironically, her argument that unveiled Egyptian women are targeted ties in with the patently false argument that if all Egyptian women veiled they would be seen as pious and therefore immune. That’s not to say that unveiled women are not more subject to abuse – it’s just to say that sometimes the question To Veil or Not to Veil shouldn’t be the first question we ask.

Sya: Eltahawy clearly states that she supports niqab bans in Europe, seeing it as a fight against a misogynist ideology. But what about the larger questions of what these bans say about citizenship and belonging?

Shireen: What Mona Eltahawy simply doesn’t understand is while she thinks she is advocating for women against a patriarchal culture and system, when she fights against Muslim women in Western countries choosing to wear niqab, she is in fact propelling that same system. Eltahawy occasionally quotes Audre Lorde and other radical and amazing feminists, although she seems to do this only selectively – in siding with the niqab ban she demonstrates that she does not accept the maxim “the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.” She would do well also to heed the wise words of Arundhati Roy:

“When, as happened recently in France, an attempt is made to coerce women out of the burqa rather than creating a situation in which a woman can choose what she wishes to do, it’s not about liberating her, but about unclothing her. It becomes an act of humiliation and cultural imperialism. It’s not about the burqa. It’s about the coercion. Coercing a woman out of a burqa is as bad as coercing her into one.”

Tasnim: That is a great quote, Shireen, and I absolutely agree. I think this is the problem with the rhetoric of “if it upsets you, that’s even better” – Eltahawy has taken to saying that she has deliberately placed herself on the fringe to “balance out” the extremists and to allow more space for those in between. Marginalizing herself as a radical Arab feminist in the limelight, as it were. And I do appreciate the need for that and applaud her refusal to compromise and go softly-softly on egregious crimes like FGM and forced marriage. I am in no way a cultural relativist. But I think there is a fine line between the valuable work of provocation and inadvertently reflecting paternalistic Eurocentric attitudes – or pushing the line so far that you become a sideshow, speaking to an admiring audience at festivals far removed from the context of the struggle. There is a tension there that the book doesn’t resolve.

Sya: The book is full of tensions and contradictions, especially with regards to her stance on hijab and niqab. For example:

“I would never connect a woman’s outfit with any unwanted physical contact or verbal abuse, but our conservative societies do” (p. 77)

and

“…the full veil, which covered her face, which I consider an erasure of her identity” (p. 67)

So which one is it? Do Muslim women have the choice to create their own destiny, or do we still need other women to save us?