A community basketball team in Cedar-Riverside Minneapolis, consisting of young Somali girls, made the news recently. These players did not gain attention from media outlets for bashing stereotypes or fighting against the Islamic oppressive patriarchy. They were lauded and positively represented for creating a solution to challenges they faced with their basketball uniforms. Their long skirts and flowy hijabs were not optimal for the courts.

So, the girls partnered with the College of Design at the University of Minnesota and created uniforms that would suit their personal and religious preferences. This successful collaboration was widely covered and the majority of the reports were pleasantly surprising and unlike any I had ever seen before; nuanced, positive and accurate.

It is not often that I am satisfied or relieved with the coverage of media and sports media regarding a story about Muslim women or girls. In my experience, their reporting is often simplistic, lazy and misinformed. Sometimes, media use narratives of Muslim girls to provide disingenuous ‘feel-good’ stories to the public. I wrote about the story of Samah, a High School soccer player from Colorado, whose team decided to wear hijabs to support her when a referee would not let her play. I was not satisfied with the constant coverage of this incident. I was actually frustrated at the way the story was joyfully hurled across the Internet by media outlets who couldn’t ask basic questions about the efficiency or effectiveness of the team’s actions.

I was beginning to wonder why so many different outlets ranging from MTV to Newsweek, would be interested in this particular tale. It is a simple tale of the ingenuity of GIRLS (Girls Initiative in Recreation and Leisurely Sports)- an organization that advocates for the empowerment of girls through sport. GIRLS was founded by Fatimah Hussein, a Somali-American woman, and for her to reach national attention on a project that combined community support with diversity and empowerment through sport is unprecedented.

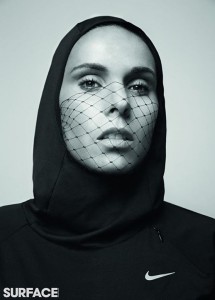

Under Fatimah’s guidance, the athletes showcased their ideas and creations at a fashion show to unveil (no pun intended) the tunics, brightly-coloured leggings and hijabs, in a variety of breathable fabrics. The story was covered by the Toronto Sun, a newspaper not widely recognized for having sympathies towards Muslim women and their choice of clothing. The emphasis in the story was that the young basketball players had created the functional and fun uniforms to accommodate their needs. They were not designed by white saviours. They were not the subject of a campaign to save the young, impressionable Muslimahs. In fact, many of the accounts of this project illustrated the capabilities and creativity of the girls.

The stories reflected the ease and intelligence with which the young girls expressed their intentions and happiness.

Does this mean there might be a change when reporting about Muslim women and their hijabs? Does this mean we can look forward to consistent reporting about contributions to the sports communities by young Muslim women? I’m not a pessimist but I wouldn’t bet my burkini on it- yet.

This is not the first time people have written on hijab and sports. In fact, the modest clothing industry is currently booming- as I discussed in a previous MMW post. There are a lot of projects and campaigns that feature women advocating or designing hijabs to include and inspire young Muslim women to get involved and commit to a healthy lifestyle.

One of the projects I am familiar personally familiar with is that of Lake Avenue Middle School in Hamilton, Ontario. The project is supported by teaching staff and raised money to add hijabs to athletic uniforms in order to create kits that could be worn by hijab-wearing girls. The Hamilton Spectator picked up the story. From the publicity of the news story, other members of the wider community decided to also donate and support the project.

In this case, the media served as an ally by amplifying the story and reiterating the need and importance of including Muslim girls in sports and various activities.

While media can be the source of reductive reporting and frustrations, they can also be of benefit to help lift up important stories and cases that require support.

While we continue to ensure that media’s representation of Muslim women isn’t shallow and reductive, it is nice to see that some stories are generating interest and attention. Moreover, they are being communicated in a manner that isn’t offensive or unhelpful.

The emphasis on the basketball team not requiring saving, but using the tools and collaborating with partners to find a suitable solution to a challenge is actually a win for all.

To reinforce the narrative that Muslim women and women of colour can find solutions and take on challenges with the proper support is the best, and most accurate way to publicize any possible story.

In my opinion, slam dunk for the coverage and for the basketball team.