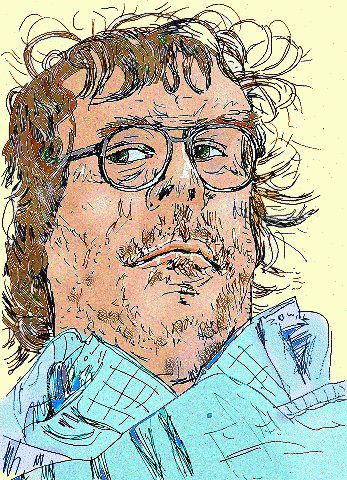

One of the things I’ve loved about the advent of social media is how we can come to have relationships with people across the globe. For me among these one of my favorites is Adrian John Worsfold. He lives in England, a country I’ve only visited once, but thanks to Facebook, I’ve come to know him, anyway. His doctorate is in Sociology. As what I’d call a participant observer, Dr Worsfold brings a keen and searching eye to that phenomenon dear to my heart known as “liberal religion.” Mostly his interests focus on the phenomenon in the British Islands. However, it turns out he also has an MA, the dissertation for which was an analysis of liberal religion on this side of the pond, specifically its largest institutional expression, Unitarian Universalism.

It is titled Plurality in Proximity: The Gospel of Unitarian Universalism for Contemporary Culture. Dr Worsfold’s summary of this study goes like this.

When Ernst Troeltsch created the typology of Mysticism he was then thinking of individualism and voluntarism as a Christian category incorporating the Reformation, the Renaissance and modernity. A form of faith and organisation that meets this typology well is creedless Unitarian Universalism. Its highly diverse plurality in proximity suggests a social gospel for how the world might incorporate difference.

This study observes how four broad belief types or general narratives have formed in contemporary Unitarian Universalism on both sides of the Atlantic. These are liberal Christianity, religious Humanism, neo-Paganism and Eastern faith. There is also pluralism. Each divides on the basis of loyalty to the narrative or the denomination. One debate is whether they can give rise to a “metatheology’ or if this is excluded. Another question is how successfully Unitarian Universalism promotes plurality.

Much theology applies itself to plurality but assumes Christian content. The nature of Unitarian Universalism demands that Christianity cannot be so privileged. This requires the methodology of both drawing on relevant approaches to theology and then applying them in an extended and perhaps unusual manner. Sociology of religion helps. A sub-theme throughout is whether, in a post-Christian culture, Christian theology is for the seminary alone and whether a broader basis of theology is possible.

If, like me, you find this intriguing, then click here to read it in full.