As many of my friends are probably more aware of than they care, I am currently working on a book on Zen meditation with particular reference to the Zen koan. (For Wisdom Publications, the working title is Learning the Language of Dragons, thank you for asking…) Anyway, as part of my researches I’ve been rummaging around the web looking for odds and ends on the subject.

And that’s how I stumbled upon something I wrote about a decade ago. The brief rumination was based on having recently read Steven Heine’s Opening a Mountain: Koans of the Zen Masters. I must admit details of that book have faded in my mind with time, but I seem to have liked it. I acknowledged how Heine is a first rate scholar, and he is, who at the same time loves koan literature while appearing to be profoundly disinterested in koans as they are used within formal Zen training.

What I really liked was how this allowed him to approach koans from left field and as a result often offering up something of genuine value to all of us including those who do use koans as a central part of our spiritual discipline. I need to go back and reread the book.

However for this brief meditation, it was one thing in particular that caught my attention at the time. Early on in the book while reflecting on the origins of koans, Heine wrote, “Furthermore, there is a medieval genre of detective story literature based on tales of intricate, suspenseful legal investigations that is also known by the term ‘kung-an.’ Most people in modern China who are aware of the term recognize it as referring to this literary genre, and the significance of kung-an/koan for Zen is less well known.”

I was quite taken with this, particularly as a fan of the mystery genre. And, I still am. While it is true that koans emerge within medieval China inspired by numerous sources, my favorite is the scholar practitioner Victor Sogen Hori’s hypothesis their principal origin is likely from Buddhist monks observing a Daoist drinking game where one person would compose a line of poetry and the next person was expected to appropriately match it. So, it’s unlikely the mystery genre was a major current.

Still, tantalizingly, the term koan (gongan or kung-an depending on one’s preferred transliteration of the Chinese) is the same word used for Chinese medieval mysteries. But they probably both derive from the fact the term is a term of law; a koan is a “public case” as in a court case.

That said. There’s quite a body of medieval Chinese mysteries. Who would have thunk?

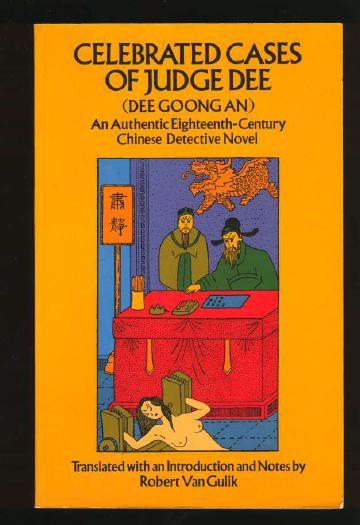

A Dutch diplomat by the name of Robert Van Gulik took an interest in the subject and translated one of the stories, the Dee Goong An, which is still in print as The Celebrated Cases of Judge Dee based upon a historical Judge Dee. Van Gulik then went on to write a number of his own, most still in print from the University of Chicago Press.

Mystery blogger Peter Rozovsky explains that the stories take place in the Tang, but were written much later in the Eighteenth century. He then adds in how it was a genre and there are other examples, such as Magistrate Pao, a series of stories about a Song dynasty figure, and like Judge Dee based in a historical person, but fiction. Leon Comber’s The Strange Cases of Magistrate Pao: Chinese Tales of Crime and Detection is a collection of six of the stories about him.

At Wikipedia there’s an article on Chinese crime fiction, with a section on Song & Ming periods (tenth through seventeenth centuries) detective fiction. “In the Song dynasty, the growth of commerce and urban society created a demand for many new forms of popular entertainment. The gong’an genre, translated as crimecase fiction, were among the new types of vernacular fiction that developed from the Song to the Ming periods. Written in colloquial rather than literary Chinese, they nearly always featured district magistrates or judges in the higher courts. The plots usually begin with a description of the crime (often including much realistic detail of contemporary life) and culminate in the exposure of the deed and the punishment of the guilty. Sometimes two solutions to a mystery are posited, but the correct solution is reached through a brilliant judge.

“The most celebrated hero of such tales was Judge Bao Zheng, or ‘Dragon Plan Bao,’ who was originally based on a historical person. Featuring in hundreds of stories, Bao became the archetype of the incorruptible official in a society in which miscarriages of justice in favor of the rich and powerful were all too common. Not all crime stories have happy endings, and some were evidently written with the aim of exposing the brutal methods of corrupt judges who—often after accepting bribes—extracted false confessions by torture and condemned innocent people to death.

“In some tales, the crimes are exposed with the aid of supernatural forces, but others display features common in Western crime fiction. For example, in one tale the dimwitted investigator is upstaged by the patient and methodical investigation of his junior.”

Wikipdia actually offers a bit longer, although still brief, tantalizingly brief article on the genre. Might be worth checking out.