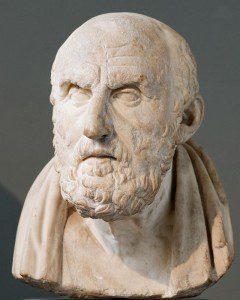

One of those things I love about Facebook are those little factoids that one can pick up. Of course you always have to be careful. So, for instance, there is a meme going around my circles right now with a picture of the Stoic philosopher Chrysippus and the caption declaring he died laughing at his own joke.

One has to dig around a bit, but I did. And as it turns out there are actually two stories about how the great Stoic (often thought of as the second founder of the school) died. One is boring, he drank too much undiluted wine, fell into a stupor and passed away. The other claims he saw a donkey eating some figs and quipped “Now give that donkey some wine to wash down the figs.” Then, as the meme goes, he fell into a fit of laughter at his own joke, and, well, died. As to the humor of the quip, I guess you had to be there.

Through the near random associations of snapping synapses, this made me think of the way humor fits into Zen. And I renewed my web search.

I found a bunch of lists of jokes, most often leading off with the one about the Buddhist going to the hot dog vendor and asking to “make me one with everything.” It must be funny because people are always telling it to me. And, I do try hard to smile when they do.

Of course studies of humor are famously not themselves very funny. Dr Freud’s study leaps to mind. Although I did find a pretty good article by Andrew Whitehead, “She Who Laughs Loudest: A Meditation on Zen Humor.” While he would never get through a dokusan (Zen interview) with his analysis, as a reflection on what’s going on, I found it pretty good.

And Mr Whitehead offered some points I was unaware of. As it turns out those Indian Buddhists who analyzed pretty much everything (I believe in their quest for salvation by finding the perfect list) had a list of the six kinds of laughter.

“sita: a faint, almost imperceptible smile manifest in the subtleties of facial expression and countenance alone;

hasita: a smile involving a slight movement of the lips, and barely revealing the tips of the teeth;

vihasita: a broad smile accompanied by a modicum of laughter;

upahasita: accentuated laughter, louder in volume, associated with movements of the head, shoulders, and arms;

apahasita: loud laughter that brings tears; and

atihasita: the most boisterous, uproarious laughter attended by movements of the entire body (e.g., doubling over in raucous guffawing, convulsions, hysterics, “rolling in the aisles,” etc.).”

Now, Andrew Whitehead quickly notes this sort of thing is alien to Zen. But. And. In fact we do inherit as a founding story Mahakashapa’s faint smile at the Buddha’s twirling a flower, which fits as the first of the Indian list, and I guess we could even call it Zen’s great inside joke.

Actually Zen’s spiritual humor tends to be a bit more slapstick. For instance in the great shaggy dog koan about master Baizhang Huaihai and a fox spirit, it concludes in the evening when the old master told his assembly the story of his meeting the spirit and what happened, which turned on questions of causality and freedom.

His senior student Huangbo stood up and said, “Sir, what if the old abbot had given the right answer every time? What would have happened then?” Baizhang smiled, perhaps like Mahakashapa, and fingering his teacher’s stick said, “Come here Huangbo, and I’ll tell you.”

Here’s a dangerous moment, if a somewhat different danger than between the fox and Baizhang, to encounter a Zen teacher with a stick in his or her hand.

Huangbo would become another of the teachers who created what we call Zen. According to traditional sources he was a giant of a man, standing nearly seven feet tall, while his teacher was barely five feet, short even for those days. When the younger monk walked up to his teacher, just before coming face to face and just out of reach from his teacher’s stick, Huangbo reached out and slapped the old abbot.

And the old abbot laughed, and laughed, and declared “They say the barbarian has a red beard, but here’s a red bearded barbarian.”

There’s a joke. Okay, slapstick, sort of, but still its another of Zen’s inside jokes.

And that’s the real question. What’s the inside joke?

What’s the real deal?

Well, there’s a novel by David James Duncan called The River Why. I think the concluding chapter says it as well as I’ve heard it. So, for your benefit, here it is. Oh, one thing to help with it. There are a lot of fishing images in the novel.

There was an old Taoist who lived in a village in ancient China, named Master Hu. Hu loved God and God loved Hu, and whatever God did was fine with Hu, and whatever Hu did was fine with God. They were friends. They were such good friends that they kidded around. Hu would do stuff to God like call him “The Great Clod.”

That’s how he kidded. That was fine with God. God would turn around and do stuff to Hu like give him warts on his face, wens on his head, arthritis in his hands, a hunch in his back, canker sores in his mouth and gout in his feet. That’s how He kidded. That God. What a kidder! But it was fine with Hu.

Master Hu grew lumpy as a toad; he grew crooked as cherry wood; he became a human pretzel. “You Clod!” he’d shout at God, laughing. That was fine with God. He’d send Hu a right leg ten inches shorter than the left to show He was listening. And Hu would laugh some more and walk around in little circles, showing off his short leg, saying to the villagers, “Haha! See how the Great Clod listens! How lumpy and crookedy and ugly He is making me! He makes me laugh and laugh! That’s what a Friend is for!” And the people of the village would look at him and wag their heads: sure enough, old Hu looked like an owl’s nest; he looked like a swamp; he looked like something the dog rolled in. And he winked at his people and looked up at God and shouted, “Hey Clod! What next?” And splot! Out popped a fresh wart.

The people wagged their heads till their tongues wagged too. They said, “Poor Master Hu has gone crazy.” And maybe he had. Maybe God sent down craziness along with the warts and wens and hunch and gout. What did Hu care? It was fine with him. He loved God and God loved Hu, and Hu was the crookedest, ugliest, happiest old man in all the empire till the day he whispered,

Hey Clod! What now?

and God took his line in hand and drew him right into Himself. That was fine with Hu. That’s what a Friend is for.

The secret is in that line. Perhaps its a fishing line. Perhaps it is the blood red thread we run into in a couple of Zen’s koans.

Another hint. Don’t cling too tightly to that thread, that line. That said, held lightly like a good fisherman, it does reveal the joke. Actually the punchline is revealed everywhere and in everything.

And if you get it, there’s at least a smile, and maybe, on occasion, even some rolling down laughter.

You’re welcome. After all, what’s a friend for?

And, okay, if that’s not clear, perhaps Ellen can help, at least a little.

You’re welcome.

After all, what’s a friend for?