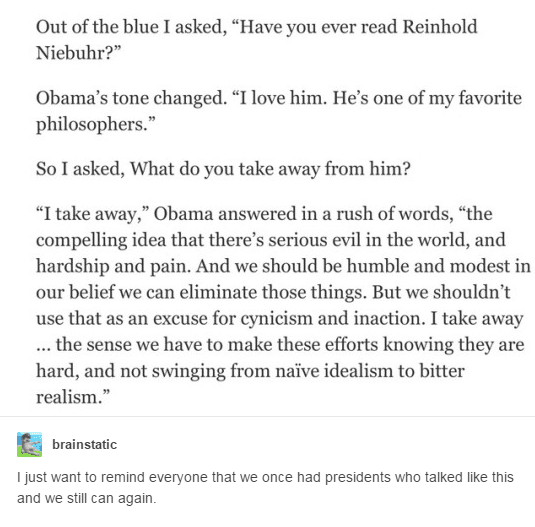

The attached image appeared in my Facebook feed yesterday.

I captured it and then googled “Reinhold Niebuhr” and “Barack Obama.” That produced almost 29,000 hits. The first google page led off with a New York Times article titled “Obama the Theologian.” It dated from 2015. The next up was from 2010 when CNN ran an article titled “How Obama’s favorite theologian shaped his first year in office.”

The upshot is that, yes, the former president was pretty deep into Niebuhr. And, yes, with that it is awfully easy to think of the current occupant in the White House and the range of his reflections about life and our place within the world. But, I find my mind and heart after a moment with that thought of the White House, goes in other directions.

I find myself thinking of Niebuhr and whether his Christian Realism might be helpful for those of us concerned with the public face of Buddhism, of how as Buddhists we engage this world.

Reinhold Niebuhr was an American Christian theologian and a public intellectual who died in 1971. He was at Union Theological in Manhattan, one of the premier Protestant seminaries, for some thirty years. He was the author of several very important books including Moral Man and Immoral Society and The Nature and Destiny of Man. At Wikipedia I learned Nature and Destiny was acknowledged by Modern Library as one of the 20 most significant nonfiction books of the last century.

Niebuhr also was one of the teachers of Masao Abe the Buddhist scholar and one of my principal teachers. Although I can’t think of anything directly about Niebuhr that Abe Sensei offered. The Christian influence was more that other great American Christian Paul Tillich. That said, I suspect some of the Christian theologian’s views must have seeped into the Buddhist teacher’s heart.

Niebuhr’s “Christian Realism” was essentially Niebuhr’s critique of the Social Gospel birthed in response to the horrors of the Second World War. Christian Realism is many things, but at its heart it is a scathing analysis of the idea of human perfectibility. And with that point some on the American political right have embraced aspects of his analysis, if interestingly doing so while ignoring his equally strong call to social engagement and particularly his care for the poor and disenfranchised. Of course the critical thing as I see Niebuhr, is that he was not talking about walking away from the world of responsibility, but rather, provided profound cautions about how we can, and who might prove to be the problem.

Today Niebuhr is probably best known as the author of the original of what has come to called the Serenity Prayer. But, as compelling as that contribution is, he offers a complex engagement with the great mess that is our communal life. For me it is that question of our limited state, what he would call “fallen,” and at the same time our need to be engaged.

Arthur Schlesinger Jr was tasked to write Niebuhr’s obituary for the New York Times. As cited in Wikipedia Schlesinger wrote Niebuhr “emphasis on sin startled my generation, brought up on optimistic convictions of human innocence and perfectibility. But nothing had prepared us for Hitler and Stalin, the Holocaust, concentration camps and gulags. Human nature was evidently as capable of depravity as of virtue…

“Traditionally, the idea of the frailty of man led to the demand for obedience to ordained authority. But Niebuhr rejected that ancient conservative argument. Ordained authority, he showed, is all the more subject to the temptations of self-interest, self-deception and self-righteousness. Power must be balanced by power.”

In a provocative article at the Atlantic, Paul Elie described Niebuhr’s political stance as a “liberal with limits.” He quotes Niebuhr and I think points to the conundrum of our lives. “To love our enemies cannot mean that we must connive with their injustice. It does mean that beyond all moral distinctions of history we must know ourselves one with our enemies not only in the bonds of common humanity but also in the bonds of common guilt by which that humanity has become corrupted.”

I think about our times. I think about our hearts. I witness the confusion of goals and means that runs a poison through the hearts of pretty much the full range of political activists from right to left. I think about my own engagement with the world, my frustrations, my passions, my own confusions of means and ends.

Reinhold Niebuhr’s theological stance is quite a bit different than mine. But I think he has in fact put a finger on the problem. We are all of us in some very real ways broken. I don’t see it as most of my Christian friends would put it. But we are incomplete. Or, to put it another way, using that old Buddhist image we are woven out of those demons that constellate as grasping, and aversion, and endlessly arising certainties. And, so we, of necessity as that lovely old line in the Christian scriptures puts it, see through a glass darkly.

However, and here I am not secure enough with my understanding of Niebuhr to reach for a commonality, for me the awakened world, Nirvana, the Pure Land, if you will, Heaven, the Realm of God, our completeness, is also exactly here, right here, in this place, in this moment. This is axiomatic to the Zen Buddhist way. It is what I understand right down to the molecules dancing in my body. This very place is it. This place. No other. This place.

Our task in this life, both spiritually, and as people living our ordinary lives, is to see both things. We must see the contingent, the partial, the incomplete as absolutely true, and as who we are, and as an inescapable fact. What Niebuhr adds into that mix is to acknowledge this incompleteness is also a statement that we see the world and ourselves in a contaminated way. Our capacity for evil is always with us. It never, ever, goes away. And, this isn’t about just “them,” some other, it is absolutely also, me.

And, and. We must see how everything is perfect just as it is. This place is the Pure Land.

Which in my tradition comes together with that lovely addendum to that assertion about how everything is perfect as it is attributed to the Zen missionary Shunryu Suzuki, who says that and then adds in, “And we all can use some improvement.”

Actually a world of improvement. And that’s where it really gets messy. That’s where we find we need for power to meet power. That’s where we find Engaged Buddhism arising. And that’s where each of us is challenged in every encounter. Perhaps we could call it Buddhist Realism.

It certainly is the conundrum. And, it absolutely doesn’t have to turn out well. The possibility of failure is always there, and often has the odds in its favor.

However. Maybe this conundrum can become the koan, the pointing and invitation described in Zen.

And, maybe, as with that mystery of ends and means, it turns out it is all found in the doing.

Just this. Only this.