A student of the way asked master Yunmen, “What did Shakyamuni Buddha preach throughout the length of his life?” To which Yunmen replied, “One teaching in response.”

Blue Cliff Record, Case Fourteen

My koan teacher’s teacher, the renowned lay master Robert Aitken commented on this simple koan that it perfectly represented the teaching of the “first age.”

Recalling that I find myself contemplating the idea of the three ages, and what it might mean. The Buddha taught that all things made of parts will come apart. And, so, of course that must include the teachings of Buddhism. In the Pali texts there are hints of what this can mean. Probably the most notable instance is the story of how when Ananda prevailed upon the Buddha to ordain women into the monastic sangha. In the Anguttara Nikaya, he declares the Order and the teachings would have lasted a thousand years, but now it will only last five hundred.

Worth noting. And, there are many byways that little line can take us toward. They can be worthy. But, they can also be distracting. And, here there is a deeper point we’re seeking. The one that can guide us through the morass of our hearts.

It is the Mahayana that runs with the idea of the teachings and their hearing running some course. And with that the idea of ages of rising, continuing, and declining. The whole mess. It even reminds me of my own life. Birth. Living. Dying. In some systems each age lasting five hundred years, in others a thousand. However, in all these schemes we find ourselves in the last, the age of decline. Mofa in Chinese and Mappa in Japanese. The age of degeneration.

Here. Now. Our age is that last age. Me, again, looking hard at turning seventy, I get the decline, and the facing of some end.

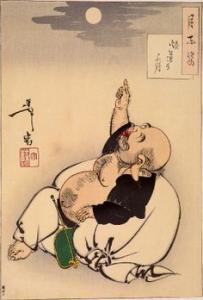

In the Pure Land schools this age is one where our practices and efforts will inevitably be of no avail. We simply cannot do it on our own. Their solution is to call upon the Buddha Amida, whose ancient vow is to take all who call upon him to the Pure Land, where it will be possible to awaken to our full liberation.

In the Zen, and particularly Soto, we are told:

“Dōgen and Keizan put no stock in theories that denied the value of traditional modes of Buddhist monastic practice, but neither did they entirely reject the notion of three stages in the evolution of the dharma. One eko text in which the ‘age of the end of the dharma’ is mentioned suggests that, in the present degenerate age, it is Dōgen and Keizan whom ordinary beings (including their descendants in the Soto lineage) should rely on. Another eko text appeals to the arhats to ‘turn the age of the end of the dharma (mappō 末法) into the age of the true dharma (shōbō 正法).'”

I find it interesting in this account from the Soto school, how we are still called to put trust in another. Maybe not Amida. But, perhaps Dogen or Keizan, the founders of the Soto way in Japan. Which, I find calls to my heart case 45 in the Gateless Gate, “Wuzu said, ‘Shakyamuni and Maitreya are servants of another. Dear one, tell me, who is that other?”

Now, what does it mean to surrender? In the Buddhist way we speak often of “self-power” and “other-power” as the two perspectives. But, what if they are each of them not quite the truth What saves when there is no possibility of being saved by one’s own effort? What saves when the only possible thing is to take matters in our own hands, to open our own hearts, to turn that light inward?

Then, who is that other Wuzu calls us to? Or, to put it another way, what is that one teaching in response?

And, with that, what is the teaching of the last age? You know. This one.

When we surrender our idea of gain and loss, when we let go of our ideas of control and anarchy, then what? Where is the healing of our heart in this moment? In this time? In this place?

I’m sure you know.