Hugo Enomiya-Lassalle was born into a Huguenot family on the 11th of November, 1898 in Gut Externbrock, in Westphalia.

He experienced the horrors of trench warfare during the Great War. By the time he was twenty-one he had become a Catholic and entered the Jesuit Order.

Ten years later he was assigned as a professor of German at the Jesuit Sophia University in Tokyo.

Enomiya-Lassalle looked beyond his academic position and began working with the desperately poor and in 1931 founded the Jochi Settlement. He struggled to get as many services to the people as he could, ranging from medical and legal services, to education. He even began a program to help educate social workers.

In 1935 Enomiya-Lassalle was assigned as mission superior for the Japanese Province for the Order. Four years later he moved to Hiroshima where a novitiate had just been established. There he had the new buildings constructed in the Japanese style. He also maintained a connection to ordinary people, serving as a parish priest. And there he also began to study Zen, first as an academic subject.

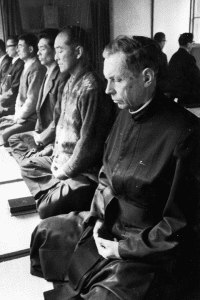

In 1943 Fr Hugo Enomiya-Lassalle sat his first sesshin.

He was present in 1945 in Hiroshima at the explosion of the Atomic bomb and was seriously hurt. In the years following he focused a considerable amount of energy establishing a church in Hiroshima dedicated to world peace. He succeeded in the project, eventually seeing the dedication of the Memorial Cathedral for World Peace in August, 1954. Among the delegates were members of the Imperial family.

Now free of what he saw as a moral obligation he turned his attention to Zen. In 1956, now fifty-eight years old, Enomiya-Lassalle formally became a student of Daiun Sogaku Harada Roshi. In addition to a regular practice he attended regular sesshin at Hosshinji.

In 1960 he wrote a book Zen: Way to Enlightenment. It was immediately censored. He traveled to Rome with the bishop of Hiroshima and with the support of several theologians, principally Johann Baptist Metz, he was able to resume his work of bringing Zen to Christians. At first he hoped to form communities of Christian Zen practitioners, but resistance from the Catholic hierarchy was such that he decided to abandon that project.

After Harada Roshi’s death he continued studying Zen, first with Harada’s successor at Hossinji, Sessui Harada Roshi. Then with another of Harada’s successors, Hakuun Yasutani Roshi. During these years he systematically worked his way through the Soto adaptation of the traditional Hakuin Takujo koan curriculum. He found the right alignment with Yasutani Roshi’s principal heir, Koun Yamada Roshi. In 1979 Hugo Enomiya-Lassalle received formal sanction as a teacher from Yamada Roshi, who was the head of a new independent Zen organization, Sanbo Kyodan (now Sanbo Zen) that Yasutani Roshi had founded to focus on training lay practitioners.

I personally wondered what it was that allowed this Catholic priest to practice Zen and even eventually to become a teacher without converting to Buddhism in some formal way.

Hugo Enomiya-Lassalle’s mystical theology, which allowed him to practice Zen and to integrate his experiences with Catholic Christianity appears to have first been informed by the French Jesuit Joseph Marechal, who developed a theory of “natural mysticism.” He also found commonality with others attempting to bridge the gaps between practicing religions like Raimon Panikkar, Henri Le Saux, and Bede Griffiths.

But principally he steeped himself in the guidance of Medieval Christian mystics like Jan van Ruusbroec and Richard Rolle. But, he seems to have been most influenced by the writings of the Twelfth Century Japanese Zen master, Eihei Dogen. A delicious feast of the world’s mystical traditions. And, perhaps, a course in natural mysticism…

It nourished him. And, through him, many others.

Hugo Enoyma-Lassalle Roshi died on the 7th of July, 1990, in Munster, in Germany. His ashes are interred at the Peace Cathedral in Hiroshima.

Me, I find this an important date. This is a moment when we can honor that liminal space where religions touch, a place that opens us up, the place that transform us – and, most of all, those people who have walked into that place.

And, of course, of course, who call to us from that place, inviting us to the great possibility of our human condition.

Many bows to the blessed Hugo and all the saints who have made the great leap beyond form and emptiness, and who have found the wise heart.

Bows.