Teitaro Suzuki died on this day in 1966. He was 95 years old and at that time widely acknowledged for his critical part in the migration of Japanese style Zen Buddhism to the West. One could fairly say we here in the West use the Japanese term “Zen” for that tradition which birthed in China and is known there as “Chan” and which traveled in addition to Korea, where it is called “Son” and Vietnam where it is called “Thien” because Suzuki said “Zen.”

His prolific and in many ways inviting approach to the spiritual tradition with an emphasis on its a-historical qualities and the experience of awakening arrived at a perfect moment. It is not possible to understate his importance at the foundations of our Western and particularly our English speaking Zen.

Teitaro Suzuki was born on the 18th of October, in 1870 in Kanazawa, in Ishikawa Prefecture, Japan, into a Samurai family. His father, like his father, and then his father before, was a physician. However, despite generations of success in worldly terms Suzuki’s father’s death when he was a child plunged the family into poverty.

The burning questions of life, partially for him arising out of seeing the apparent random vagaries of life drove him into a deep spiritual quest. While he was raised within the Jodo Shinshu tradition Tetario began to look beyond that tradition, reading and speaking with people, particularly drawn to Christianity and eventually to Zen.

Young Teitaro was not able to afford to enter university. So after High School he became a school teacher. A few years later with the help of an older brother, he was able to enter the University of Tokyo studying classical Buddhist languages while at the same time beginning to sit at Engakuji Rinzai Zen temple.

He became the student of the master there, Imakita Kosen, under whom he had his first experiences of kensho. He also received his Buddhist name, Daisetsu, which means “great humility.” Although in later years he would say it actually meant “great clumsy.” When Kosen Roshi died Suzuki continued with the rosh’s principal heir, Soen Shaku.

Later, when Soyen Shaku, Kosen Roshi’s successor as the master of Engakuji was in America for the World Parliament of Religions he became friends with the publisher and scholar Paul Carus. Carus asked the roshi if he would stay and help him with translating and publishing Zen Buddhist texts into English. Soen Roshi declined, but recommended his lay student Daisetsu Teitaro Suzuki.

With that Suzuki moved to Illinois and into the Carus household. There he assisted in translating the Dao de Ching, not a Buddhist text, but foundational to understanding East Asian spiritualities. And then they began work on what would become Outlines of Mahayana Buddhism. Also while there Suzuki met, fell in love with, and married Beatrice Erskine Lane.

The couple returned to Japan where Suzuki took up a professorship at Otani University. At that time he also met Shinichi Hisamatsu and became connected, although never formally with the Kyoto School of Buddhist philosophers. Suzuki would teach in Japan and the united States for the rest of his life, and for a number of years later in his career as a visiting professor at Columbia.

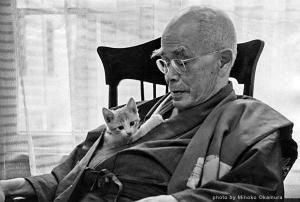

D. T. Suzuki, as he was best known, would travel widely, lecturing across North America and Europe. And most importantly, perhaps, he wrote. Eventually, over a hundred books. Much of these efforts focused on Zen.

His circle of influence included the Catholic monk, peace activist and mystic, Thomas Merton, psychologists like Eric Fromm, Karen Horney, and most notably Carl Jung, musicians like John Cage, poets like Gary Snyder and Alan Ginsberg, and, perhaps most importantly Alan Watts. Watts own books on Zen were essentially popularizations of Suzuki’s work. And they were very popular. Through them if washed through Watts’ idiosyncratic, Suzuki’s Zen perspectives reached the general educated English speaking readership like an atomic bomb.

There are many reasons to criticize D. T. Suzuki, some of them even deserved. There are serious allegations about Suzuki’s support of Japanese imperialism. Others say the allegations lack sufficient nuance, and in some situations in fact misrepresent what Suzuki actually said. I am more inclined to this later view. However there is a shadow hanging over the old teacher, which cannot be ignored.

And, then there’s his presentation of Zen. Here is a significant issue for us with cascades that play out to this day. Alan Watts’ popular expositions of Zen, which were the first widely distributed interpretation of Zen, while founded upon Suzuki’s work was wildly idiosyncratic. That’s not really Suzuki’s responsibility.

But the prolific Suzuki did bring some problems of his own in his presentations, which were pretty much all that any English speaker had access to for several years. And he presented a not fully historical, but rather a romanticized version of the Zen dharma. Subsequent scholars and teachers have had to work with, against, and around this. Although in some ways his resonances with Idealism, German and English Romanticism and particularly American Transcendentalism probably made Zen accessible in ways that would otherwise not be so. And which allowed Alan Watts his own distortions.

All this said in our contemporary categorizations D. T.Suzuki can probably best be categorized as a modernist Buddhist.

These criticisms noted, his scholarship was impeccable, and his contributions remain solid. And, to put it baldly, if there were no D. T. Suzuki, Zen in the West even vaguely as we experience it, would not exist.

It is said that D. T. Suzuki’s last words were “Don’t worry. Thank you! Thank you!”

Yes. Thank you! And. Endless bows.