“What is REAL?” asked the Rabbit one day, when they were lying side by side near the nursery fender, before Nana came to tidy the room. “Does it mean having things that buzz inside you and a stick-out handle?”

“Real isn’t how you are made,” said the Skin Horse. “It’s a thing that happens to you. When a child loves you for a long, long time, not just to play with, but Really loves you, then you become Real.”

“Does it hurt?” asked the Rabbit.

“Sometimes,” said the Skin Horse, for he was always truthful. “When you are Real you don’t mind being hurt.”

“Does it happen all at once, like being wound up,” he asked, “or bit by bit?”

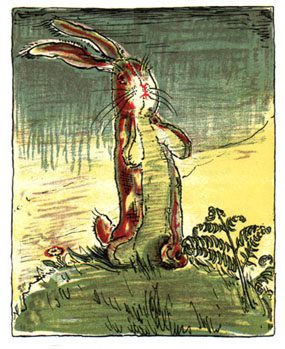

“It doesn’t happen all at once,” said the Skin Horse. “You become. It takes a long time. That’s why it doesn’t happen often to people who break easily, or have sharp edges, or who have to be carefully kept. Generally, by the time you are Real, most of your hair has been loved off, and your eyes drop out and you get all loose in the joints and very shabby. But these things don’t matter at all, because once you are Real you can’t be ugly, except to people who don’t understand.”

Velveteen Rabbit: Or, How Toys Become Real

by Margery Williams

This past Sunday I had the pleasure of preaching at the Universalist Unitarian Church of Santa Paula. I love the church, a small historic Universalist congregation founded shortly before the beginning of the twentieth century, making it by California standards a historic congregation. Their current minister, the Reverend Maddie Sifantus is an old friend as well as a colleague.

I preached on the idea of “growing a soul.” It’s based in my sense that we don’t have souls. Certainly not souls as something that lives in us like a passenger on some bus, but which is ultimately unaffected by the trials and pains of our lives and will simply step away from this mortal husk at death. But rather that soul is something that grows within the very mess that is our lives.

Maddie chose the concluding passage from Margery Williams children’s book the Velveteen Rabbit as a reading to lead into the sermon. It’s that passage I lead this reflection with. I was mildly embarrassed to see it pretty much summarized my own reflection, but presented much better and closer to the point for which I was reaching.

Margery Winifred Williams was an Anglo-American author best recalled as an award winning writer of children’s books. Her father was a British barrister, classical scholar, and journalist. He died when she was seven. Margery’s mother returned to America with Margery and her sister. My cursory search for biographical details says nothing about her mother, who must have had a hard time raising two children on her own. And I wonder about what that hard time meant for the girl who would become the author.

Still, in the limited biographical materials I found online, it is her father who seemed to haunt her. She credits his love of literature and his untimely death as profound markers for her. Margery’s first novel, the Late Returning was published when she was seventeen. She would go on to marry an Italian national and rare book dealer Francesco Bianco. They had two children, Cecco and Pamela, who grow up to be an artist & illustrator. It seems their lives were peripatetic, the family traveled and settled for varying amounts of time in England, Italy, and the United States, Margery Williams Bianco died in 1944.

I could find next to nothing about Margery having any formal religious background. Although she does credit the poet Walter John de la Mare as her “spiritual mentor.” Again a cursory search finds little about formal religious influences on de la Mare. His obituary published by the Glasgow Herald hints at the substance of his spirituality, saying de la Mare’s “poetry and prose have a kinship with mystical literature in being unconditioned by historical time and his verse in particular belongs to that rare and timeless strain in literature that includes some of Shakespeare’s songs, the poetry of Vaughn and Traherne, Blake’s Songs of Innocence and Experience and Coleridge’s Kubla Khan.”

Okay. A passion for the imaginal life, the dream worlds. But it is always also marked by the realities of life, especially change, especially death. So, within it all I’m finding Williams’ vision a sort of a spirituality of magical realism, where the earthly life and dream meet.

Works for me.

Then, as I look at that brief passage that was read ahead of my sermon and shared as the preface to this small reflection I find a sort of koan. Koan: a matter to be made clear. A statement about reality bound together with an invitation.

So. Like with a koan throwing the backstory away. And then just looking at the words as they present…

“What is real?” is a first question for anyone who dreams. We clearly live in multiple worlds. But, which, if any, is true? Life. Hurt. Loss. Death. Love. These words arise from the heart of our existence. And the human quest becomes one of digging into these various worlds of perception and interpretation, seeking an encounter that might bring the worlds together, might lead to some great reconciliation of heart and world.

But, immediately, with the very next draw of breath we’re invited to look a bit deeper than the surface of things. Although, I’ve been warned, we’ve been warned by our teachers on the great Zen way that the surface of things is it, too. But, we do need different eyes the eyes of imagination and of dream. We need the eyes that really are open.

Here we find the call to full engagement. We are not invited to turn away. The dream realms, the real ones, the dreams that speak truth, do not take us to some far away land. Rather we must engage the world as a child playing with us. We must engage the world, this world, the one that plays rough, that pulls and tears and, and, well, and loves us. Love here is attention. Love here is presence.

And it is hard. And it takes times.

And things happen. On the Zen way we may be graced with insights small and large. Often they happen. They genuinely are graces. And. The real part is the living into. And it takes time.

Being and time are one thing. A lot of things are this one thing.

Those of us who are impatient about this project are going to be hurt. Well, we’re all going to be hurt. Hurt comes with the territory. Hurt is a big part of the territory. But the invitation is into each day and each moment, and then to let them pile upon each other, for as long as they do. Graces come, but they are not shortcuts taking us away from the project.

So, the hurt and the joy, they become facets of a same truth. Here the discoveries of the heart and the life we live are found as one thing. Here, the sadnesses of our lives and the consolations of our lives are each of them facets of a single life.

Dreams…

And Margery, well she sings to us, all of us, wherever we are. Young and excited and fearful: she opens the way. Dreams. Or, perhaps, we have grown old, as the joints hurt, as the hair thins or is lost, as our eyesight, the part that is solely the eye of the flesh, begins to fail. Here, too, she calls us to how we find ourselves the repository of a world of dreams.

The world becomes real. And so do we. The dream sings…

All one thing.

All our joy.

The project of the real…