Thomas Merton, Catholic Trappist monk, memoirist, essayist, activist, and mystic, died on this day in 1968.

He was participating at an interfaith monastic conference in Bangkok, Thailand. It appears he touched a faulty floor fan and it sparked a heart attack. By coincidence it was the twenty-seventh anniversary of his entrance into Gethsemane Abbey, a rural Trappists monastery not far outside of Louisville, Kentucky.

And. Today is the fiftieth anniversary of his death. To my mind, to my heart, a worthy moment to reflect on this remarkable man and his ministry.

Thomas Merton is probably most widely known as the author of the best selling spiritual memoir Seven Storey Mountain. However this book was followed by many others, and ironically, the cloistered Merton ended up enthralling two generations of spiritual seekers. And counting…

Also, his influence would extend well beyond his church. In 1937, early on in the formation of his spiritual life, and well before his anchoring his quest within Catholic monasticism, he read Aldous Huxley’s Ends and Means. This led to a life-long interest in Eastern religions, particularly Islamic Sufism, Hinduism, and Buddhism. He would not only read in these traditions but he engaged in long correspondences with practitioners, monastics, teachers, priests, and scholars in these traditions.

The Wikipedia article on Merton tells us he “was perhaps most interested in—and, of all of the Eastern traditions, wrote the most about—Zen. Having studied the Desert Fathers and other Christian mystics as part of his monastic vocation, Merton had a deep understanding of what it was those men sought and experienced in their seeking. He found many parallels between the language of these Christian mystics and the language of Zen philosophy.”

This would prove very important to me. Continuing the article, “In 1959, Merton began a dialogue with D. T. Suzuki which was published in Merton’s Zen and the Birds of Appetite as “Wisdom in Emptiness”. This dialogue began with the completion of Merton’s The Wisdom of the Desert. Merton sent a copy to Suzuki with the hope that he would comment on Merton’s view that the Desert Fathers and the early Zen masters had similar experiences.

“Nearly ten years later, when Zen and the Birds of Appetite was published, Merton wrote in his postface that “any attempt to handle Zen in theological language is bound to miss the point”, calling his final statements “an example of how not to approach Zen.” Merton struggled to reconcile the Western and Christian impulse to catalog and put into words every experience with the ideas of Christian apophatic theology and the unspeakable nature of the Zen experience.”

Because of this broad and sympathetic interest in the world’s mystical traditions and especially his take on Zen, and with that the enormous popularity of his writings, some would opine that his death was not accidental. I personally do not find that particularly plausible. But, it is repeated, and needs to be noted, if only in passing.

As I noted Thomas Merton touched many questing hearts. And, he certainly put a permanent mark on my spiritual life. I’ve read much of his ovure, and consider him among the foremost of those teachers I’ve had who I knew only through their writings.

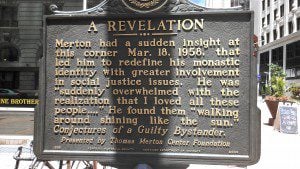

In 2013 the Unitarian Universalist General Assembly was held in Louisville. For me it was something of a Merton pilgrimage. First, downtown there’s a marker, the only state sanctioned marker I’ve ever encountered that notes someone’s spiritual awakening, in my spirituality, kensho. Merton’s full account speaks to the moment that transformed his heart, and in its flowering influenced so many, including, again, me.

“In Louisville, at the corner of Fourth and Walnut, in the center of the shopping district, I was suddenly overwhelmed with the realization that I loved all those people, that they were mine and I theirs, that we could not be alien to one another even though we were total strangers.

“It was like waking from a dream of separateness, of spurious self-isolation in a special world, the world of renunciation and supposed holiness. The whole illusion of a separate holy existence is a dream.…This sense of liberation from an illusory difference was such a relief and such a joy to me that I almost laughed out loud. And I suppose my happiness could have taken form in the words: ‘Thank God, thank God that I am like other men, that I am only a man among others.’

“It is a glorious destiny to be a member of the human race, though it is a race dedicated to many absurdities and one which makes many terrible mistakes: …A member of the human race! To think that such a commonplace realization should suddenly seem like news that one holds the winning ticket in a cosmic sweepstake. And if only everybody could realize this! But it cannot be explained.

“There is no way of telling people that they are all walking around shining like the sun. They are not ‘they’ but my own self. There are no strangers! Then it was as if I suddenly saw the secret beauty of their hearts, the depths of their hearts where neither sin nor desire nor self-knowledge can reach, the core of their reality. If only they could all see themselves as they really are. If only we could see each other that way all the time. There would be no more war, no more hatred, no more cruelty, no more greed…I suppose the big problem would be that we would fall down and worship each other.”

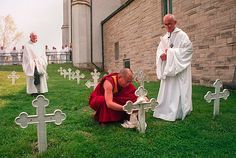

He proceeded to live his life out of that moment. An example for us all. Later during that week in Louisville my colleague and friend Erik Wikstrom and I drove out to the monastery, where we laid flowers on Fr Merton’s grave. He deserves to be remembered.

His teachings were multiple, and I especially felt informed by his versions of the Daoist master Zhuang Zhou. And while not agreeing with everything he said, I loved Zen and the Birds of Appetite and Mystics and Zen Masters. But for me the most important of his teachings are presented within the small book The Wisdom of the Desert.

The curation was carefully designed to emphasize those areas of possible compatibility with Zen Buddhism. Later reading more comprehensive collections such as Benedicta Ward’s magisterial Apophthegmata Patrum, the Sayings of the Desert Fathers, or even Helen Waddell’s more introductory The Desert Fathers, reveals a fascinating, wildly diverse, and even compelling version of an ascetic Christianity.

And, yes, within that wildness there are moments that look quite “Zen.” Merton, from his unique perspective as a deeply committed Christian monastic, but also one with a genuine opening of the heart that was not capturable by a single tradition, he could present a Zen-like take on this ancient ascetics and give a text book of the spiritual life for us today. Maybe, in fact, something a bit more than Zen-like.

For instance, in Father Merton’s version.

Some elders once came to Abbot Anthony, and there was with them also Abbot Joseph. Wishing to test them, Abbot Anthony brought the conversation around to the Holy Scriptures. And he began from the youngest to ask them the meaning of this or that text. Each one replied as best he could, but Abbot Anthony said to them: You have not got it yet. After them all he asked Abbot Joseph: What about you? What do you say this text means? Abbot Joseph replied: I know not! Then Abbot Anthony said: Truly Abbot Joseph alone has found the way, for he replies that he knows not.

In addition to the questions of curation, I am also aware of the dangers of seeking meaning for one’s own spiritual way in the utterances of someone on another way. But, my goodness, sometimes. Sometimes.

When asked what is Zen, the Korean Zen master Seung Sahn said, “Only don’t know.” This is the great secret of Zen spirituality. And, frankly, the secret gateway for us all. And so we find this message collected as case twenty in the Book of Serenity.

Dizang asked Fayen, “Where are you going?” Fayen replied, “I am wandering about aimlessly.” Dizang asked, “So, what do you think of this wandering about?” Fayan said, “I don’t know.” Dizang replied, “Not knowing is most intimate.”

It doesn’t really matter for our purposes who the players in this story are, although I find it interesting that they’re real historical people. Still, we can, and I believe it very helpful, to think of them as the part of our minds that believes it is in control and the part that knows better. “How are you doing?” I can ask myself. “Oh, wandering about,” I might reply. Particularly, right now. Interestingly, some versions of the text say “wandering about on pilgrimage.” Others, however, say “wandering about aimlessly.” These days, wrapped in not knowing, I prefer the second. Then pushed to respond to how I feel about this, I really, really understand that line “I don’t know.”

And, Christians get it. (Yes, not all Christians. The same can be said about many Buddhists…) We got it in that saying from the Desert Fathers. And, here’s something important. Thomas Merton wasn’t inventing anything. He was just pointing. So, as a passing example here’s another Christian text that also points in this direction. The more common version for the title is the Cloud of Unknowing. It could just as easily, just as accurately be titled the Cloud of Not Knowing.

Not knowing. Only don’t know. The cloud of unknowing.

In my own experience, it means that while I like to plan and analyze, sometimes, sometimes in the most important places, I have to surrender my dreams of control, and let what is, be. For me it means shifting a bit, and letting my body guide me, rather more than my head. Right now, living within the bow, within the not knowing, I discover things.

So, I just cannot say how important Thomas Merton was for me as I’ve walked my own spiritual path. There is no doubt in my heart that the leading current for me is Zen Buddhism, and more specifically within the Soto school of Zen as articulated most clearly by Eihei Dogen and the Soto reformed Zen koan curriculum system of spiritual training begun by Daiun Sogaku Harada. But, finding the currents of truth within my natal spiritual tradition has also been a life long interest. Christianity and Buddhism. Each currents of my life. And, nowhere else, have I found it all brought together as helpfully, as healthfully, as in Thomas Merton’s teachings.

He presents us with a field of dreams. The dreams of our not knowing. My dreams hint at things, and I need to notice. My body’s aches and joys tell me things, and I need to notice. Chance encounters and fragments of conversation take on new and luminescent qualities, and I need to notice. Here the water bubbling up out of the well reveals itself, flowing freely, informing, nurturing, opening new ways. It’s something glorious, as well, of course, as unsettling, and occasionally even frightening.

Not knowing. Only don’t know. That cloud of unknowing. Just as Thomas Merton taught.

This not knowing is most intimate. Beyond East and West. Found both in East and West. It reveals who I really am, it loosens my sense of boundaries, shakes off stories of control and certainty, and, and in all that; reveals a wide and wild world as my true home.

Just as Thomas Merton taught. His life and the many blessings of that life deserves celebrating. I’m so glad to know those lovely people in the American Episcopal church observe today formally as a feast in his honor.

And, today, on the fiftieth anniversary of that feast, I pray prays of gratitude.