The Origin of Religion

A Sermon

Delivered at the

Unitarian Universalist Church of Fullerton

on the

10th February, 2019

James Ishmael Ford

A couple of years ago I was in Connecticut to co-lead a Zen retreat. As the retreat ended one of my co-leaders, Mary Gates, who is both a fully authorized Zen teacher and an Episcopal priest excused herself. Mary explained she had to say mass for the small congregation she served as vicar. Being me, I asked if I could tag along.

The service was held in a tiny stone chapel in West Cornwall. The town is a Norman Rockwell image of old New England. It even has a covered bridge. The chapel, well, built in New England or picked up and moved from some bucolic English countryside, it was picture perfect. There were eighteen of us in that little chapel, and we pretty much filled it.

The service itself was Prayer Book Rite II with all that means for those familiar with the history of Episcopalian religious services. For me as a progressive it’s filled with awkward masculine by preference language and as a Buddhist with a full-on dualistic God out there and you and me, down here theology. Not my cup of tea. And.

First, there were the people. I can’t read hearts with any clarity, certainly not by outward appearances. But it felt the full range of who we are as we come to church on intimate display Young people maybe there on their own, maybe just to make family happy. Older people, some quite elderly, where the actions of the pews came from decades of practice. Maybe done out of rote, but it looked more like well-traveled paths toward something. I’ll return to that. And a fair number in between, some probably happy to have a service that ends early in the morning. Others, well, hard to say. A large basket of life. Although it sure felt most everyone was fully present as they were. Sadness. Hope. Longing. Joy. You know, the human things. The things that we call religious, or, perhaps, today we might rather say spiritual.

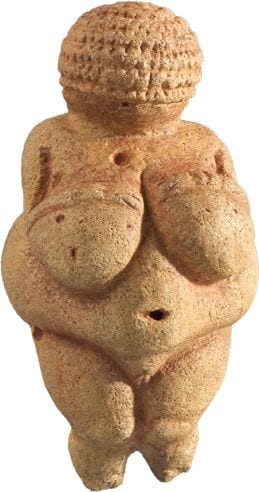

Let’s stick with religion for a bit. Today I find myself concerned with the origins, or maybe it’s the origin of religion. What is the font from which it springs? Or, what tributaries gather to make it what it is? Admittedly, to try to understand what it is, or what our most distant ancestors religious or spiritual views were, are, frankly, more than elusive. What happened, what folk thought before writing, what five thousand years ago, a tad more, can only be inferred by rapidly fading collections of artifacts as we trace back to mother Africa. But they are compelling. Like that Venus of Willendorf figurine, maybe thirty thousand years old. It evokes feelings. And thoughts flow from looking at it, like Pentecost fires. But beyond that atavistic feeling of ancient recollection, what?

I think of those ancient artifacts, and others, haunting evidences like ancient, ancient mountain trails used by our Neanderthal cousins as well as our direct ancestors. Trails that wind through mountains in ways that seem to include at some disadvantage to efficiency but allow enhanced views of distant beauty. There is a cave in Span with what appears to be a 40,000 years-old grave for a Neanderthal toddler. The grave site is surrounded by animal horns, including bison and red deer. Similar sites for homo sapiens with what appear to be intentional burials including grave goods and evidences of layers of flowers poured over the body that seem to range back at least fifty and maybe even a hundred thousand years.

This said as far back as we know with any certainty, religion and culture are profoundly entangled. Any attempt at pulling specifically religious perspectives out of the cultural matrix seems to date no later than during the European Reformation. And no one has ever succeeded in fully untangling religion from the rest of the mess of human lives in specific cultural contexts. In fact, from my perspective, one of the less pleasant aspects of religion is assuring cultural conformity. It sure seems true that religions have always been tied up with the transmission of culture, reinforcing the various ways in which people identify themselves and, critically, separate themselves from others. That us and them thing has from ancient times been religiously reinforced.

Much of what shapes what we usually think of as religion birthed at several places on the Eurasian continent in what is now called the Axial Age. It’s a term coined by the philosopher Karl Jaspers for a culturally fruitful time roughly between the eighth and third centuries before our common era. Jaspers identified the religions that birthed in Greece, Judea, Persia, India, and China all fulfilled that culturally reinforcing, essentially conservative and conserving task within their differing cultures.

Although, critically, with the birth of Buddhism, then a bit later Christianity, and lastly Islam, we find missionary religions. They no doubt carry with them cultural elements from their places of origin. Lots. But they mostly bring certain “big ideas” at their heart that are meant to be shared with the whole world. And with that the absolute connection between religion and given cultures would no longer be quite the same.

That partial untangling has allowed us to notice religion as something not necessarily part of preserving a specific culture. And it has opened the possibility for us to look at that part of what it means to be human that we call religious or spiritual. And, it turns out, from the beginning it’s been a mess. Speculation on what this might be from some sense of a universal energy, to ancestor worship, to scapegoats and sacrifices, to averting natural disasters, to guaranteeing the planet doesn’t simply spin into eternal darkness, to begin a list. The list of things that seem important in religions is very long. And, it doesn’t really add up. Frankly, I’ve found the Twentieth century Unitarian Universalist minister and theologian Forrest Church’s observation most helpful. “Religion is our human response to the dual reality of being alive and (knowing we will) die.”

I suggest when people speak of being spiritual but not religious, they are continuing our uniquely modern, or, maybe that’s post-modern, or, I have trouble keeping up with these things, perhaps it’s a post-post-modern stance of relentless untangling and examining of the parts in hope of understanding the whole. In this case they, okay, we are generally trying to jettison those aspects of religion concerned with preserving and transmitting culture, and most of all those unsavory parts defining who is in and who is out of the group. With that what we call spirituality emerges as a hopefully “purer” distillation at the heart of that matter. Although what that might be remains far from clear.

One can certainly question the degree to which we can extract ourselves from culture. Me, I suspect not a whole lot. But, like the scholar and religious historian Karen Armstrong suggests, I also believe we may indeed be in a new Axial Age, for me starting with the European Enlightenment enriched by a comparative religious sense, particularly arising out of our modern interreligious dialogue. It’s something where things have been taken apart sufficiently, and, surprisingly a new whole is emerging. Something totally unexpected. Like a new dawn, a world perspective. If you will a universalism. Not quite like the earliest forms of universalism, extending heaven to all. But, equally, maybe more deserving of the word universal. Of course, it is contending with those older views. And, in this moment, I certainly wouldn’t put money on what view will prevail. Personally, I can’t put money on our species surviving for a whole lot longer.

Still. Also. Out of all this, my personal stab at defining religion: Religion is that part of culture where our hopes and fears regarding life and death are expressed through stories and symbolic actions. And, I think the spiritual at the heart of it, the secret truth that floats through all religions, that universalist current sometimes held up, sometimes scorned and suppressed, but always present is a knowing that within all our diversity there is some mysterious unity. And, frankly, I think it is our only hope for survival as a species.

If there is a universalism emerging within a new Axial, it is this. Each thing as it arises, you, me, a rock, a star is precious and beautiful. And. It, that you, that me, that star arises out of a profoundly connected web of relationships. That web itself is simply the relationship of things, coming together, holding for a moment, falling away. But each thing as it presents is the universe itself. And, we human beings, blessed beyond all reason, get to notice this.

So, back to that mass in that little Episcopal chapel in West Cornwall, Connecticut, on the eastern side of the North American continent, on a small planet spinning around a middling star at the edge of one of a million million galaxies. As the service worked its way through the story of Jesus and his disciples gathered at their meal. Finally, the consecrated bread and wine were offered to all who were present. Me, I’ve been to many Episcopal services over the years. Episcopalians are without a doubt my favorite Christians. But, I never take communion. As lovely as that tradition is, I always felt just enough of a separation that partaking in that most intimate part of the service never felt appropriate. Not respectful. Not right.

This time was different. Maybe in some degree it was my relationship with the priest. But that hardly would be enough. Something else happened in that little stone chapel. I saw. I noticed. The whole universe was present. All the angels of Western faith and all the devas of the East were present and circling around that little altar that somehow became the navel of the cosmos. And without thinking about it, without worry about theology or proper decorum, without any concern but a longing to come ever closer to the moment of creation, I stepped into that small circle. And I received communion.

This is not the only time I’ve had such a sense of invitation. I can offer a number of examples. But, I’m a Zen teacher. So, when we retired and Jan and I returned home to Southern California a mutual friend made sure I met a local Japanese Zen priest, the Reverend Gyokei Yokoyama. He leads a Japanese-American congregation in Long Beach where he conducts services and preaches sermons and tends to the pastoral needs of the people he serves. As I noted mostly Japanese Americans. In addition to his ministerial duties he leads a Zen meditation group several mornings a week. Sadly, few in the congregation are interested in meditation. And his little group are mostly converts, mostly in the moment at least of European descent.

And. While I am responsible for my own Zen group, I love going to the morning sits he leads. I love it for a couple of reasons. One, I’m not in charge. I get to, as we say in the Zen way, just sit. And over these past couple of years I’ve come to love that early morning schedule. The way the light comes up from the darkness as we begin, the mix of smells, particularly the slight hint of mildew mixed with sandalwood incense that instantly returns me to my youth sitting at the old Berkeley Zendo where I first began my practice many, many years ago. It is delicious.

But, the main reason I’m doing this is that I have committed myself to trying to relearn the sacramental functions of a Soto Zen priest. I first learned them pushing on fifty years ago. But after my time in the monastery I ended up practicing with a koan teacher who was not a priest, and well, that part of my Zen life more or less fell away. In my dotage I’m on a path of integration and a part of that is more fully understanding the priestly part of my path.

I’ve found this in some ways just relearning to bow. Never a bad thing. Not a bad thing for any of us. And, so, Wednesday and Friday mornings, I at least figuratively put on the black robe of a novice priest, sit a bit, and then try to master the liturgical ropes presented by a kind and generous teacher.

One day, not long ago, I found myself standing near the altar as the sensei approached the altar. The form is closely prescribed. Every motion has a thousand years of practice behind it, within it, as it. He walked up with his hands folded at his chest, as he stepped to the altar itself, he put his hands together palm to palm. He picked up a waiting stick of incense and held it to his forehead, bowing slightly.

And, I realized in that moment as Gyokei offered that incense for the world it was the same moment as when Mary held up the chalice in an offering for the world. The truth has always been there.

Hidden in plain sight.

You want to know the origin of religion?

“To see a World in a Grain of Sand/And a Heaven in a Wild Flower/Hold Infinity in the palm of your hand.”

Just notice. Just be present. Just this. Just this.

The origin of religion.

Amen.