ALL BEINGS, ONE BODY:

A TRUE HISTORY

OF UNITARIAN UNIVERSALISM

A Sermon

delivered at the

First Unitarian Church of Los Angeles

On the 24th of February, 2019

24 February 2019

I’m pretty sure the first time that Unitarian Universalism floated to consciousness for me was pushing on forty years ago when I was working at Wahrenbrock’s Book House in San Diego. It was one of those great bookstores of what is becoming a bygone age. It stocked mostly used and antiquarian books. Me, among other things, I was charged with tending to the used religions and metaphysics section. It included a really substantial collection of pamphlet literature, much from the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

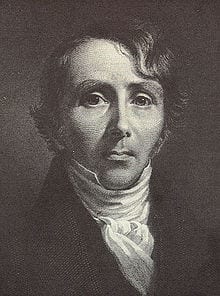

I recall a day sorting through those pamphlets. One denounced Kaiser Wilhelm II as the antichrist with prodigious scriptural citations. Another revealed the pyramids were originally built just outside of Dublin but were later moved through a conspiracy between the Romans and, of course, the British. And, that’s when I stumbled upon a pamphlet whose cover read simply “On Unitarian Christianity.” The author was listed as William Ellery Channing. It was published in Boston, Massachusetts.

I took it home and read it. Now many years later I re-read it, and frankly, I don’t know what I found quite so compelling. But, compelling it was. It was a sermon delivered in 1819 in Baltimore on the occasion of the ordination of Jared Sparks (who would one day become president of Harvard College). The preacher was, as I noted, the Reverend William Ellery Channing. He was the most prominent of the liberal and rationalist wing of the Congregational churches in New England.

Inspired by the spirit of the Enlightenment these liberals had publicly denied much of the then dominant Calvinist orthodoxy, insisting there was nothing inherently evil about our human condition. And, critically, they saw Jesus as a prophet whose life and teachings were the important thing, not his death. This did not go over well with that Calvinist majority. Looking for the worst epithet they could hurl at the liberals they dug up the word Unitarian.

That 1819 sermon was when the leader of the liberal wing said, okay, we kind of like it. Yes. We are Unitarians. This would be one of a dozen incidents that took place in the first quarter of the Nineteenth century, which taken together would birth the institutions that would become the American Unitarian Association, the Universalist Church of America, and in good time our Unitarian Universalist Association.

Me, just out of several years in a Zen Buddhist monastery and looking for a path of integration between those experiences and my birth-right Christianity this sounded like just the thing. That very next Sunday I attended a local UU church service for the first time. I promptly fell asleep during the sermon.

Somewhat cautioned by that experience, but not daunted, I began to study the liberal religious tradition. Attending church services. Talking. Reading. More talking. And, gradually I found, yes, while it is filled with people who don’t always live up to its ideals, that also meant there was a place for me – as I was. As I am. There was, there is, a place for a large range of people. Today there are rationalist atheists who claim Unitarian Universalism, Christians who are UUs, Jews who are UUs, Buddhist UUs, Hindu UUs, pagan UUs – well, the list goes on. And on.

The diversity among us is so broad it can sometimes seem there is no center at all. But, this isn’t so. As the UU divine Herbert Hitchen was wont to say, “Unitarian Universalism is an alternative religion, not an alternative to religion.” Some might debate that point. And, yes, we can be, and sometimes are an alternative to religion. But to leave it there is to miss something. Ours is a way that is broad and inclusive and allows lots and lots of flavors. But, at the same time, it is something which has distinctive features, a sometimes smoldering, sometime burning coal at our heart.

My charge today is to lay out what that might be. I’ve found the best way to approach this is historically. So, I’m going to briefly speak to the mythic origins of our tradition, the stories we like to tell about ourselves. Then, really, really, fast cover some of the historical aspects, that means institutional parts. Because, and this is an axiom of our way: we are what we do.

And then finally I’ll talk a little about that alternative religion which emerged out of this history. I should be able to address this without damage to the deeper points within, oh, two and a half hours. Okay, three. However, as I appear to have ten or twelve-minutes left, let’s see what I can do…

We arise out of Christianity, and in some ways remain so, if at the very edge of that tradition. Therefore, among the early Chrisgian theologians we claim a few such as Arius who challenged trinitarianism and Origin who posited an ultimate reconciliation with God that excluded no one, not even the devil. These are our mythic ancestors.

The straight line that would shape those who would create the communities from which we derive takes inspiration in a handful of reformation thinkers. We love the proto-scientists. So, Galileo and Giordano Bruno are part of our pantheon. We absolutely adore Michael Servetus, a Spanish physician who in the middle of the Sixteenth century vividly mocked not only trinitarianism but the pope. That he would eventually be burned at the stake by John Calvin gives us together with Bruno, a martyr.

From that fruitful period our most important and in some ways direct ancestor would be an Italian Renaissance thinker Fausto Sozzini, in Latin Faustus Socinus. He took that more than bold step to proclaim that Jesus, while perhaps the greatest of men, was just that, a human being. The spiritual tradition named for him Socinianism proclaims the complete humanity of Jesus. Here myth and history begin to join.

Socinus fled Italy, and is the most important of the theologians who would develop the Polish Brethren in the 16thand 17thcenturies. People inspired by him established a printing press at Racow, from which Europe would be flooded with pamphlets and books, most notably a Unitarian Catechism. We’ll return to that. Socinus would also be the principal thinker helping to form the Unitarian church in Transylvania.

Here we get several of the most important figures of our mythic history. The first of these is Francis David. He was an astonishingly fruitful thinker. Beginning as a Catholic priest, he converted to Lutheranism, becoming the Lutheran bishop in Transylvania. Then he became a Calvinist, and before long become their bishop. And, finally, through a passage from anti-trinitarianism, with some assistance from Socinus, to something more like what we understand as Unitarianism. He would first serve as court preacher to King John Sigismund, and then as the founding bishop of the Hungarian speaking Unitarian church. The second of these most important figures is the king himself. John Sigismund followed a near identical spiritual journey from Catholicism to Lutheranism to Calvinism. And, then, meeting David joined him in the advancement of a Unitarian church. He would go on to proclaim one of the earliest legal calls for religious tolerance, and usher in a brief spiritual and intellectual flowering that would only end with his untimely and highly suspicious death in 1571.

Their Unitarian church, however, would survive. It continues to this day in two divisions, one in Romanian Transylvania and the other in Hungary. There would over the years be slight connections between that church and the later English-speaking movement from which we descend.

This noted, and treasured, for the most part the emergent and for our purposes historic movement that would become English speaking Unitarianism, Universalism, and finally Unitarian Universalism would be for the most part be a phenomenon of the European Enlightenment.

The Enlightenment is the seedbed from which our actual church organizations would emerge in England and North America. In the Eighteenth and very early Nineteenth centuries in England an anti-trinitarian current ran deep within the English churches, both established and dissident. John Biddle is generally believed to have translated the first English language version of the Racovian Catechism, our most important link to Continental Unitarianism. (We UUs are always suckers for salvation by bibliography.) And he suffered for it. Mary Wollstonecraft stands as an example of unitarian thinkers within that fruitful period. The list is pretty long. And, well, we have about five minutes left.

But it was the Anglican priest Theophilus Lindsey who in April, 1774, conducted a public service attended by many of London’s social and intellectual elites. They included the scientist and Presbyterian minister Joseph Priestly and the colonial American representative to the court, Benjamin Franklin. In that service Lindsey took off the white robe of a priest and put on the black robe of the academy, think full on Enlightenment rationalism, and preached the first sermon in what would become the English Unitarian church.

Later escaping a mob that burned his laboratory and chapel, Joseph Priestly would come to America and establish the first church in this country to call itself Unitarian. Although, as we know from the anecdote about William Ellery Channing, Unitarianism had already established itself as an alternative to the harsh Calvinism of New England’s Congregationalism. A rolling schism would take place over the first decades of the Nineteenth century, a signal marker of which was Channing’s sermon in Baltimore.

Which takes us full circle to my fateful encounter with that pamphlet. But it is absolutely not the end of the matter for what would become Unitarian Universalism. First, it is critical to note the whole Universalist current. During the Enlightenment period as Unitarians began to emerge, so did Universalists. The Unitarians were largely from the upper classes and concerned with the ethical life. The Universalists were workers, farmers, small merchants who saw that God was love. Their lives turned on knowing ever more deeply what that love really is. The Unitarians soon embraced Universalism, and the Universalists Unitarianism. But they remained divided by that greatest of chasms, class.

Next come the Transcendentalists. While for most of America Transcendentalism is our first great native American literary flowering, it was in fact a heated theological debate among the second-generation Unitarians. Nearly all the leaders of the movement were Unitarians, including Margaret Fuller, Elizabeth Palmer Peabody, Henry David Thoreau, as well as the ministers Ralph Waldo Emerson, Amos Bronson Alcott, Fredric Henry Hedge, and the immortal Theodore Parker.

They proclaimed a new vision in which nature was the true holy scripture and human intuition the holy spirit. In some ways a natural enough next step for those who accepted the natural world and all that might mean. We are what we do. Intriguingly, they also read the sacred scriptures of the world’s religions which were just becoming available. And these two things, a bias to naturalism and respect for the human mind, together with a broad and sympathetic engagement with the world’s religions would dramatically change the trajectory of both Unitarianism and Universalism.

Then, I’m sorry, there’s way too much territory to cover here. Some of it very much worth digging into. But, not now. Jumping ahead, by the end of the nineteenth century influenced by evolutionary theory and other scientific advances, another perspective began to emerge. A total naturalism with an increasing confidence in the ability of the human mind to sort out what needed sorting out. When the Humanist Manifesto was published in 1933 many of the signers of the manifesto were Unitarian and Universalist clergy.

While several of the leading figures in Unitarian and Universalist humanism, such as Curtis Reese, John Dietrich, and Charles Potter could best be understood as naturalistic mystics, the nontheistic stance quickly hardened for many into a pretty fervent anti-theism. This anti-religious religious humanism would come to mark the movement as the American Unitarian Association and the Universalist Church in America consolidated in 1961 to form the Unitarian Universalist Association.

A broadly rationalist and anti-theist humanism would become the dominant current in UU thinking for most of the balance of the twentieth century. And, for a time it flourished. In the decades following the Second World War the fellowship movement, lay-led founding of congregations spread the UU alternative religious stance across the continent.

By the end of the twentieth century new currents began to arise within the movement. I like to cite the 1988 interviews with Joseph Campbell conducted by Bill Moyers called the Power of Myth as a convenient marker for this next great shift. If you hold it as a metaphor, the shift was from a broadly Freudian spirituality, toward a broadly Jungian approach. Again. Please don’t hold me to this literally. It was a shift toward something we might call a new spirituality. And it is where we are today.

During this time two groups in particular began to emerge, neo-pagans and Buddhists. Each in their own way would flavor the shape of our Association. Where this will lead, it is impossible to say. Today, while we look and act like Protestants, if usually not Christians, our dominant perspectives remain humanism, now flavored with a broad and generous reclamation of Western spiritual language, inclined toward the earth-centered forms, and by a continuing interest in Buddhist meditation and sometimes even Buddhist philosophy. The big chunks. There are many others. Some of our very interesting thinkers identify as Hindu, and many as Christian. I like to characterize us as through our own peculiar evolution has having become a home-grown form of Daoism – a naturalistic and rationalist spirituality. With, and this is really important, no requirement one must hold one particular perspective over another. We always have escape clauses to our spiritual assertions. It is the creative tension between our respect for the individual and our sense we are all of us intertwined.

I would be remiss to not mention our ongoing concerns with social justice. Driven by our intuition of an interdependent web binding us and the world together, our spirituality today is located for many in the work of justice.

Our first challenge was slavery, which we met with mixed effect. Few of our spiritual ancestors owned slaves, but many owned the ships they were transported on. Challenged from thundering pulpits like that of Theodore Parker we eventually came mostly to stand against that evil. We didn’t see African American clergy until the Baptist minister William Jackson crossed over to us in 1860. Egbert Ethelred Brown began the modern era of African American service among us in 1912. Since then a small but steadily growing number of clergy of color have joined our ranks. Racial reconciliation remains a challenge for us.

Our second great challenge was the rights of women and I think it connected with LGBTQ concerns. And we have a somewhat better history in that regard. The first regularly ordained woman in a generally recognized denomination was Margaret Fuller ordained a Universalist minister in 1863. Today fully half of our clergy are women. The first openly gay minister to come out was James Stoll in 1969. In 2002 Sean Dennison was the first openly transgender minister to be called to serve a congregation, our church in Salt Lake City.

Today we face the disaster of climate change as a spiritual issue. Many of us are focused on immigration and immigrant rights. And internally for us the dismantling of unconscious white supremacist structures. Our insight into interdependence as a core spiritual assertion turns out to be a call to a revolution of the heart.

To summarize. We have two great currents that have informed who we would become that were articulated in the early Nineteenth century by Unitarians as “salvation by character,” that is we are what we do. A harsh and at the same time compelling message. The other is the Universalist “love over creed,” rephrased by the contemporary African American Unitarian theologian Thandeka as “love beyond belief.” Here I think we find the great intuition we call the Seventh Principle. We are each of us connected. No one is saved unless all are. Interdependence. Radical interdependence.

And from that a challenge. The alternative religion. Our Unitarian Universalism brings a message of healing, and of hope for each and every person and this lovely small planet spinning through the great night. We are all in this together. As one family. All connected.

All beings, one body.

Amen.