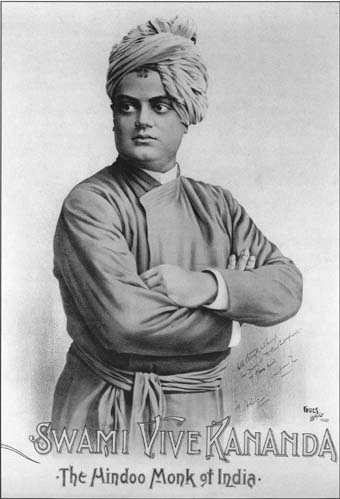

I consider Swami Vivkeananda one of those signal figures in the dawning of our modern era of world religious encounter.

This was true for me personally, where an exploration of Vedanta, Sri Ramaakrishna, and his great disciple Swami Vivekananda were my first tentative exploration beyond Christianity…

The Swami was born in Calcutta on this day, the 12th of January, in 1863, as Narendranath Datta. His was a professional family, his father an attorney.

From childhood religion was Narrendranath’s great obsession. As an undergraduate he studied religion and philosophy, both Eastern and Western. He then became interested in the Hindu reform movement the Brahmo Samaj, joining a breakaway branch, the Sadharan Brahmo Samaj.

He also met Sri Ramakrishna. For a time Narendranath remained more interested in the Western (and Unitarian and Transcendentalist) influenced Braho Samaj, but followng his father’s death, he gradually gravitated to Ramakrishna and his ecstatic spirituality.

His Wikipedia article tells us “Although he did not initially accept Ramakrishna as his teacher and rebelled against his ideas, he was attracted by his personality and began to frequently visit him at Dakshineswar.” Narendranath “initially saw Ramakrishna’s ecstasies and visions as ‘mere figments of imagination’ and ‘hallucinations.’ As a member of Brahmo Samaj, he opposed idol worship, polytheism and Ramakrishna’s worship of Kali. He even rejected the Advaita Vedanta of ‘identity with the absolute’ as blasphemy and madness, and often ridiculed the idea.”

However, under Ramakrishna’s tutelage he gradually found his quest to know God overtaking everything else. Soon he found himself falling into ecstatic samadhi states. And then he had his great awakening. Named Vivekananda by his teacher he quickly became Ramakrishna’s leading disciple. When his teacher died, Swami Vivekananda became the head of what would become the Ramakrishna Math.

With his trip to speak at the 1893 World Parliament of Religions Swami Vivekananda would become one of the most important interpreters of Hinduism to the West as well as a leading spiritual figure in India itself. In the West the Vedanta Society, which represents the Ramakrishna Order, has become a significant spiritual force, influencing many people including Aldous Huxley and Christopher Isherwood.

The Wikipedia article summarizes how “Vivekananda propagated that the essence of Hinduism was best expressed in Adi Shankara’s Advaita Vedanta philosophy. Nevertheless, following Ramakrishna, and in contrast to Advaita Vedanta, Vivekananda believed that the Absolute is both immanent and transcendent. According to Anil Sooklal, Vivekananda’s neo-Advaita ‘reconciles Dvaita or dualism and Advaita or non-dualism.’ Vivekananda summarised the Vedanta as follows, giving it a modern and Universalistic interpretation:

Each soul is potentially divine. The goal is to manifest this Divinity within by controlling nature, external and internal. Do this either by work, or worship, or mental discipline, or philosophy—by one, or more, or all of these—and be free. This is the whole of religion. Doctrines, or dogmas, or rituals, or books, or temples, or forms, are but secondary details.”

His influence is near incalculable. Among other things I think he is critical in the shifting of Western Universalism from the belief that the dead are all reconciled to the divine to the belief that all religions contain the deepest truth.

Summarizing his influence, Wikipedia suggests, that Swami “Vivekananda was one of the main representatives of Neo-Vedanta, a modern interpretation of selected aspects of Hinduism in line with western esoteric traditions, especially Transcendentalism, New Thought and Theosophy. His reinterpretation was, and is, very successful, creating a new understanding and appreciation of Hinduism within and outside India, and was the principal reason for the enthusiastic reception of yoga, transcendental meditation and other forms of Indian spiritual self-improvement in the West.”

An amazing figure.

As an example what follows is based out of a talk he delivered on Sunday, February 25, 1900, at the First Unitarian Church of Oakland, in California. The following notes of this lecture are as reported in the Oakland Enquirer together with their editorial comments. Thanks to the Reverend Kathy Huff, one time Senior Minister of the First Unitarian Church of Oakland for this text.

***

The announcement that Swami Vivekananda, a distinguished savant of the East, would expound the philosophy of Vedanta in the Parliament of Religions at the Unitarian Church last evening, attracted an immense throng. The main auditorium and ante-rooms were packed, the annexed auditorium of Wendte Hall was thrown open, and this was also filled to overflowing, and it is estimated that fully 500 persons, who could not obtain seats or standing room where they could hear conveniently, were turned away.

The Swami created a marked impression. Frequently he received applause during the lecture, and upon concluding, held a levee of enthusiastic admirers. He said in part, under the subject of “The Claims of Vedanta on the Modern World”:

Vedanta demands the consideration of the modern world. The largest number of the human race is under its influence. Again and again, millions upon millions have swept down on its adherents in India, crushing them with their great force, and yet the religion lives. In all the nations of the world, can such a system be found? Others have risen to come under its shadow. Born like mushrooms, today they are alive and flourishing, and tomorrow they are gone. Is this not the survival of the fittest?

It is a system not yet complete. It has been growing for thousands of years and is still growing. So I can give you but an idea of all I would say in one brief hour.

First, to tell you of the history of the rise of Vedanta. When it arose, India had already perfected a religion. Its crystallisation had been going on many years. Already there were elaborate ceremonies; already there had been perfected a system of morals for the different stages of life. But there came a rebellion against the mummeries and mockeries that enter into many religions in time, and great men came forth to proclaim through the Vedas the true religion. Hindus received their religion from the revelation of these Vedas. They were told that the Vedas were without beginning and without end. It may sound ludicrous to this audience — how a book can be without beginning or end; but by the Vedas no books are meant. They mean the accumulated treasury of spiritual laws discovered by different persons in different times.

Before these men came, the popular ideas of a God ruling the universe, and that man was immortal, were in existence. But there they stopped. It was thought that nothing more could be known. Here came the daring of the expounders of Vedanta. They knew that religion meant for children is not good for thinking men; that there is something more to man and God.

The moral agnostic knows only the external dead nature. From that he would form the law of the universe. He might as well cut off my nose and claim to form an idea of my whole body, as argue thus. He must look within. The stars that sweep through the heavens, even the universe is but a drop in the bucket. Your agnostic sees not the greatest, and he is frightened at the universe.

The world of spirit is greater than all — the God of the universe who rules — our Father, our Mother. What is this heathen mummery we call the world? There is misery everywhere. The child is born with a cry upon its lips; it is its first utterance. This child becomes a man, and so well used to misery that the pang of the heart is hidden by a smile on the lips.

Where is the solution of this world? Those who look outside will never find it; they must turn their eyes inward and find truth. Religion lives inside.

One man preaches, if you chop your head off, you get salvation. But does he get any one to follow him? Your own Jesus says, “Give all to the poor and follow me.” How many of you have done this? You have not followed out this command, and yet Jesus was the great teacher of your religion. Every one of you is practical in his own life, and you find this would be impracticable.

But Vedanta offers you nothing that is impracticable. Every science must have its own matter to work upon. Everyone needs certain conditions and much of training and learning; but any Jack in the street can tell you all about religion. You may want to follow religion and follow an expert, but you may only care to converse with Jack, for he can talk it.

You must do with religion as with science, come in direct contact with facts, and on that foundation build a marvellous structure.

To have a true religion you must have instruments. Belief is not in question; of faith you can make nothing, for you can believe anything.

We know that in science as we increase the velocity, the mass decreases; and as we increase the mass, the velocity decreases. Thus we have matter and force. The matter, we do not know how, disappears into force, and force into matter. Therefore there is something which is neither force nor matter, as these two may not disappear into each other. This is what we call mind — the universal mind.

Your body and my body are separate, you say. I am but a little whirlpool in the universal ocean of mankind. A whirlpool, it is true, but a part of the great ocean.

You stand by moving water where every particle is changing, and yet you call it a stream. The water is changing, it is true, but the banks remain the same. The mind is not changing, but the body — how quick its growth! I was a baby, a boy, a man, and soon I will be an old man, stooped and aged. The body is changing, and you say, is the mind not changing also? When I was a child, I was thinking, I have become larger, because my mind is a sea of impressions.

There is behind nature a universal mind. The spirit is simply a unit and it is not matter. For man is a spirit. The question, “Where does the soul go after death?” should be answered like the boy when he asked, “Why does not the earth fall down?” The questions are alike, and their solutions alike; for where could the soul go to?

To you who talk of immortality I would ask when you go home to endeavour to imagine you are dead. Stand by and touch your dead body. You cannot, for you cannot get out of yourself. The question is not concerning immortality, but as to whether Jack will meet his Jenny after death.

The one great secret of religion is to know for yourself that you are a spirit. Do not cry out, “I am a worm, I am nobody!” As the poet says, “I am Existence, Knowledge, and Truth.” No man can do any good in the world by crying out, “I am one of its evils.” The more perfect, the less imperfections you see.