I just watched a good introduction to Zen meditation by Daishin Morgan, retired abbot of Throssel Hole Buddhist Abbey. While we are both dharma successors of the late Houn Jiyu Kennett, I’ve never met him. I was impressed with his introduction.

It inspired me to provide some thoughts of my own, along with some videos about Zen meditation, all gathered together on a single page.

As a beginning some of my own thoughts which are posted at our Empty Moon website.

Meditation in the Zen tradition really boils down to three things. Sit down. Shut up. Pay attention.

First that sitting down. Now, the Buddha himself taught there were four postures for meditation, sitting down, standing up, lying down and walking. Each has its place, and each of us will find a closer affinity with one or another. That said, for most of us sitting down is going to be the best thing to do, both to start and to maintain a regular practice.

In the Zen community sitting meditation is where we always start.

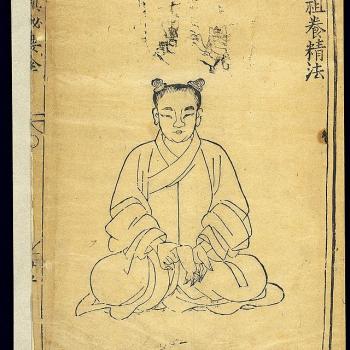

First we deal with the body. There is what to do with your legs, there is what to do with your torso, and there is what to do with your hands and head and eyes.

In Zen we use two pillows, a small round pillow called a zafu and a larger flat square of a pillow called a zabuton. The zafu rests on the zabuton. If you sit to the front half of the zafu your legs will naturally incline to the floor. It is important to work toward getting at least a single knee to the ground. And, obviously, one need not run out and purchase pillows. Folded blankest can do just fine.

The ideal position is called a full lotus where the feet rest on the thighs. With stretching and over time, many people can do this. It is the most stable of positions with the bottom raised by the zafu and the knees both dropped to the ground a solid triangular base is created. The half lotus with one foot on the thigh is slightly less stable but works, fine. Resting one foot on a calf is called the quarter lotus, or in my circles the half ass lotus. Setting one foot in front of the other, but with the knees both to the ground is called Burmese. They all work.

Other options include kneeling and either sitting on a sidewise zafu to take pressure off the ankles or using a kneeling bench, called a seiza bench for the same effect. Some use computer chairs, which naturally creates the same base. And, finally, one may sit in a chair. The secret here, as with all these positions is to have the bottom slightly higher than the knees. This causes that triangular base. It isn’t as stable, and most people who are serious about the practice, unless there is a significant physical obstacle, find getting on the ground on the floor the best thing.

Of course this is just establishing the base for seated meditation. The idea is to sit with an erect and upright posture. We do this by holding the back straight, by which we mean the natural “s” cure of the human upright posture. Resting comfortably on that triangular base, a slight push at the small of the back, together with holding the shoulders back slightly should reveal what upright looks and feels like. If you don’t feel comfortably upright swaying the torso back and forth or in shrinking circles will take you to that centered and upright position.

If you tuck your chin in slightly and mentally align your ears upright with your torso, your head will be resting comfortably upright. Place your hands in your lap, placing your left hand in your right, allowing the thumbs to touch lightly, creating an oval. This is called the “cosmic mudra.” Pull your elbows out slightly. In Zen meditation one sits with the eyes open, with the gaze falling forward to the floor a couple of feet ahead.

If you’re just present, noticing, but not following the thoughts and feelings as they rise, this is called zazen, shikantaza, or just sitting.

Of course few of us are just sitting. We worry about the past, we plan for the future. So, when beginning the practice most teachers encourage some slight intervention to help with concentration. There are a number of methods including counting and sometimes mantras.

We recommend one of the simplest of the forms. Take five breath cycles and put a number on each inhalation and exhalation. So, one on the in breath. Two on the out breath. And so on until ten. Then start over again.

Just breathe naturally. The posture will encourage diaphragmatic breathing, filling the lungs from the bottom. But just let this happen naturally. And if doesn’t, don’t worry about it.

And even with all this the mind still wanders. When you notice, and it isn’t if, but rather, when you notice you’ve lost count, just return to one. If you discover you’ve slipped into a robotic counting and are at twenty-six, just return to one.

The catch is rather than return to one we often feel a need to place blame somewhere. The two basic directions are inside and out. We notice we’ve lost count and we blame ourselves, not good enough, not smart enough, too much bad karma from a previous life. Of course, what has just happened is that instead of noticing and returning we’ve entered a meta-distraction. Just come back to one. Others prefer to blame the environment, if it wasn’t for my neighbor’s grumbly tummy, if it wasn’t for the kids playing upstairs, if it wasn’t for the traffic outside. Same meta-distraction, just pointed in a new direction. Return to one.

There’s a third distraction that can be even more seductive: but, this is a good idea. The solution to some problem, the lot for the great American novel, or, just a deeply satisfying train of thought. The deal is you’ve committed to this practice for a brief period of time. In Zen the number ranges from fifty minutes down to twenty-five. If the thought is really that important it will return. Come back to one.

Think of the practice as “olly olly oxen free.” Come home, come home, all is forgiven.

Just sitting. Just this.

A baseline practice is probably about half an hour a day most every day. Serious practitioners usually sit more, often a lot more. But, you will notice this practice touching your heart if you can maintain that half hour a day, most days.

An occasional retreat, half day, full day, two, three, five or seven days can be enormously enriching.

But, at first, just getting your bottom on the pillow regularly is all that is required. If you hope to develop a real practice at the beginning regularity is vastly more important than duration. Five or ten minutes a day three days a week done is way more important than setting an intention to sit two hours a day and not doing it.

There are a number of strategies that help. It helps to sit at the same time each day. They say the morning is golden and the evening silver, but in truth, whatever time of day you can do consistently is best. Sitting in the same place each day is helpful, if you can. And if you can reserve the space, create a small shrine or something that marks it out for this purpose this can be helpful. All these are strategies, and not to add to the burden. Do what you can, as you can.

Beyond that I recommend some of the classic texts. First, Eihei Dogen’s Fukanzazengi. And with that, I’m not really sure if it should follow or precede Dogen’s instructions, Keizan Jokin’s Zazen jokinji.

And. Many of us need visual instructions. Here are four I feel comfortable sharing…

***

Daishin Morgan, retired abbot of Throssel Hole Buddhist Abbey.

Daido Loori, late abbot of Zen Mountain Monastery.

Yokoji Zen Mountain Zen Center.

Hazy Moon Zen Center