A CRICKET, SINGING

Zen Commentary on Gateless Gate, Case 10

James Ishmael Ford

A student of the intimate way came to the master Caoshan Benji. He said “My name is Qingshui. I am solitary and destitute. Please give me alms.”

The master responded, “Venerable Shui!”

Quinshui immediately responded, “Yes!”

Master Caoshan replied, “You’ve already sipped three glasses of the finest wine in the nation. And yet you say you’ve not put the cup to your lips.”

Gateless Gate, Case 10

Anyone familiar with koan literature knows how it is littered with similar anecdotes where someone goes to the master, stating her or his longing for the great intimacy, only to be told it has already happened. One could say it starts with our second Chinese ancestor Huike, who as he asks the question of Bodhidharma is so desperate he cuts off his arm as a token of his sincerity. As that dialogue plays out, he is invited into a moment where he cannot find a root to his mind. Or, maybe we can discern it as the Buddha himself takes a flower in his hand and twirls it. The response, the perfect match that echoes through time and space comes when his disciple Mahakasyapa smiles.

If we have embarked on the spiritual quest, particularly if we’ve found our hearts calling us into this Zen way, the question for all of us is what is this intimacy of the moment? And how is it supposed to heal the ache of our lives?

And. Well. What about today, this day where we’re caught up in the moment of “social distancing?” Where we are being called into physical separation? At this moment where in our country dangers stalk the streets and casual conversations can lead to death?

Thanks to Facebook I’m hearing lots of questions. For some it’s how do I live in this apartment or house all by myself? Many jokes have followed. One particularly telling one says this moment will end with a lot of people who’ve mastered the arts of cooking, or with a serious drinking problem. Jokes that point to realities of social isolation that are not good. For the most secure of us these are hard times.

More haunting, perhaps, are those alone or maybe with a family, who have no savings, no other income than the one they lost with the many shutdowns we’re now facing. People who wonder when they will not have a place to live? Or, money to buy food?

And while not, to the best of my knowledge on my social media, there are still more people who are wandering the streets in a morass of confusion. Perhaps not even fully understanding what’s going on. Okay, as if any of us really fully understands. But experiencing their already constrained world shrinking even more. For some of us shelter and food, just plain food are the pressing questions of the moment.

So solitary and destitute can have many meanings. The plain and upfront ones are pretty harsh. Maybe a bit clearer about how harsh right now.

Now in the Zen universe with our fondness of upsetting conventional understandings of things, where, as Kapleau Roshi was fond of saying, slander becomes praise, to say I am destitute can actually be bragging.

The so-called first koan, where the student of the way asks if even a dog, even I have Buddhat nature, and where Zhaozhou responds, no. That no touches the matter as an invitation to letting go of every idea. And in that way of speaking negation and affirmation touch. So, when saying I am solitary and destitute, I can be saying I’ve tasted the intimae way and I am not entangled.

So, there’s that. And it is real. And it is intimate.

So, there’s the poverty of not knowing whether one is going to eat. There’s definitely that. But this style was coined within a spiritual community where the precariousness of life was always present in ways our contemporary cultures often can ignore. This moment we’re in is a bit more like the way things have been during large swaths of human existence.

So intimate is as intimate as a kiss. And, intimate is as intimate as death.

And, between these two points, we find we live. Here. This world. The messy one. And with that, what about now? Within the tumble of events, those multitudinous causes and conditions that make up our lives, what does this Zen way call us to?

What is the invitation?

Caoshan was one of the great masters of the ninth century, Together with his teacher Dongshan Liangjie, they were the two founders of the Soto school. And so direct lineage ancestors of ours. That means in addition to everything else this koan opens for us, we’re also getting a little glimpse of our family stories.

Most commentaries on this case point out it is considered something involving the other side of our awakening, that after the “fifteen day,” after the full moon of our experience. After we profoundly understand the great “no.” Or, as most of us who undertake koan practice say, mu. After mu. There is something in that for all of us wherever we are on the intimate way.

This reminds us and invites us. Our awakening is found in every step, that’s what we’re promised. And specifically within this story, Quinshui can simply be making a statement of his own experience. And despite the assertion of depth, opening himself to further instruction. There is something sweet where someone who seems obviously well into the way is still bowing.

And something really important is being revealed.

Zenkei Shibayama in his classic commentary on the Gateless Gate collection concludes his reflection on this case telling an anecdote about the Japanese master Bankei. A lay disciple tells him, “My wisdom is tightly confined within me and I am unable to make use of it.” This sounds like a genuine self-assessment. It is a major marker on our spiritual lives, where we’ve touched something, we feel some change, but at the same time it doesn’t seem to manifest in our lives. It’s more like a recurring dream. So, after stating her condition, the student of the way asks, “How can I use it?”

It. Mu. No.

It. Here we see a common problem of the inner way. How do we reconcile what we find on the pillow with the actual events of our lives? There’s a famous two panel cartoon in the Zen world. In the first panel the master says to the disciple, “You have completed your training. But there is one more test.” It seems there is always one more test. The second panel shows the disciple back home for a Thanksgiving meal.

Bankei hears his student. He leans forward, and says, “Please come a little closer.” Of course, in many Zen stories what follows is a whack with the stick. You want to taste the intimate moment, well, a slap will show you one aspect of this moment. I suspect the student knows this. Fair chance the student has witnesses this. Whatever, she immediately steps forward. To which Bankei responds, “How beautifully you’re using it.”

It. No.

Quinshui responds to Caoshan’s call, yes! Quinshui is called and steps forward.

It. Yes.

Aitken Roshi in his commentary on this case chooses to invite us into a reflection on the dark moments of our practice. In the arc of the spiritual life we come to hard parts, dry spots, desert spots. These happen to everyone who walks the intimate way, whatever the tradition we might be following. It’s part of our human way to deal with the various shadows and wounds which are part of the many elements of who we are. In time it all shows up.

What we’re all invited into by the circumstances of the moment is something akin to that arc of our individual lives. But it is also a calling out of our practice ways of engaging the difficulties of this life right now. Our collective lives. Our social lives.

If this time is like all other times, an invitation into who we really are, what does that look like in a time of plague?

What is it here? What is it now?

The hint, we usually want a hint. A pointer. Is in that nub of the story where the old master calls your name and you respond. A call and response so intimate there is little that can be seen as separating them. That famous box and its lid.

That’s it.

It is the student of the intimate way who has touched something but feels incomplete. Who is then called to step forward. And knowing there are so many ways that stepping forward can be dangerous, nonetheless does.

The call and the stepping forward. The no becoming a yes.

That’s it.

The consequences of our actions will unfold. We live in a multiconditional world. We are the product of vast numbers of causes and conditions that just for a moment brought us into existence. It all will shift. And we will cease. The “we” that we think of as “me.”

But there’s something else going on. And as we surrender our need to control it all, in whatever the ways we’ve chosen to do so, then that “yes” and the step forward become bodhisattva actions, become the actions of awakening.

Then we discover that play of cause and effect within which we live and breathe and take our being is not mechanical. It is alive. It is our life.

It is the “it” of it all. The deep no becomes a deep yes.

And It is a yes that touches every corner of the universes.

It is the poet Issa’s lovely summation of life and death and all between. (In Jane Hirshfield’s translation)

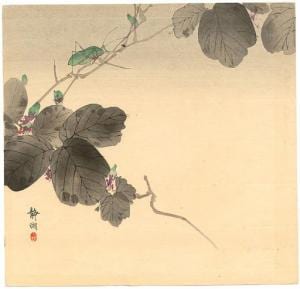

On a branch

Floating downriver

A cricket, singing

Everything revealed. Your life. My life.

Yes.

(The image of a cricket on a branch is by Seiko Okuhara)