WHAT WILL YOU DO?

Commenting on a Traditional Zen Koan

James Myoun Ford

The Case

There was an old woman who supported a hermit. For twenty years she always had a girl take the hermit his food and wait on him. One day she told the girl to give the monk a close hug and ask, “What do you feel just now?”

The hermit responded in verse.

An old tree on a cold cliff;

Midwinter – no warmth.

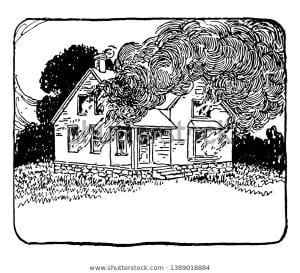

The girl went back and told this to the old woman. The woman said, “For twenty years I’ve supported this vulgar good-for-nothing!” With this she threw the monk out and burned down the hermitage.

Case 154, Entangling Vines, translated by Thomas Yuho Kirchner (slightly adapted)

I was rummaging around my files when I stumbled upon a reflection on this old koan that I wrote a couple of years ago. I first encountered the story of that old woman, the hut, the young serving girl, that turn, and where it led in Paul Reps & Nyogen Senzaki’s delightful little book 101 Zen Stories. It may be one of the first koans to capture my imagination. Long before I began serious Zen practice and ages before I found a teacher on the koan way.

It has bubbled and boiled. And on occasion I’ve found experiences in my life that recall that koan. That reflection I found was my exploring some of one of the more powerful meetings of that story and my own life.

That meeting of these two things happened in August of 1990.What is that, just shy of thirty years ago? I was in deep into my clinical pastoral education unit, that is my chaplaincy training program, at the Pacific Presbyterian Hospital in San Francisco. It was the weekend and I was on call. As the hospital didn’t have an emergency room, I didn’t think much of being on call. No one was ever called. I no longer remember precisely, whether late at night or early in the morning, whatever, I was asleep when my pager buzzed. It took a moment to understand what was going on, but my brain fairly quickly moved into gear, and I called in. I was told to get over to the hospital as quickly as I could.

I arrived and was directed up to one of their two operating theaters. Putting on a mask I walked in and was confronted with a team surrounding what I soon learned was a twelve-year old girl. Whatever was going on looked pretty bad. The whole team was totally focused on the child on the bed. No one there was interested in me, or what I had to offer.

So, I went to the one of the two waiting rooms. The other had curtains drawn and I assumed was empty. This one was filled with family. Two generations, the older Cambodian refugees, the younger their American children. I announced I was the chaplain. There was a small woman sitting at the center of the field of energy that filled that overcrowded room. She was surrounded by the women, mostly, two holding her hands, others touching her. The men were for the most part standing in an outer ring. They all looked at me as what I said was translated. There was a pause. And, then the woman let go with a string of what I knew was invective. A slightly embarrassed looking older man said, “she’s cursing you, Father. And God. She wants to know why?”

I wasn’t exactly sure what had happened. I knew it was something bad. And I was sure I didn’t have an answer to her why. I replied I didn’t know what had happened. But I was here to be with her and the family for as long as they wanted.

Her interest in me ended and she returned to some inner world of memory and sorrow and, I could feel it, fear. I stayed. I’d long since learned as a Zen practitioner that the secret was sitting down, shutting up, and paying attention. I was learning this was equally the truth for chaplaincy and ministry. As the clock ran its course, out of that silence, and soft crying, and anxiety, others did want to talk. Some had questions, more wanted to just say something.

Finally, two men in scrubs came into the waiting room, an older man, and a younger one. I noticed the younger man found his shoes incredibly important. He was unable to raise his eyes from them. The older man took a deep breath and said they had done all they could. But she never recovered from the heart attack. A twelve-year old girl, I thought. A heart attack. It was something congenital. No one could have foreseen. And they just couldn’t revive her.

There must have been something more. But I don’t remember. Details. Instructions for next steps.

The doctors left the room.

Everyone sat there. Already tears were not enough. Some deeper blanket of sorrow had covered everyone.

It took a while for the family to leave. First the small woman and about half the room. Then, in twos and threes they all left. Each stepping into the hall, and most of them taking the elevator. I stayed planning on waiting until the last one left.

Then, just as the last of them were stepping into the elevator, the doors to the other waiting room flew open. As I said I hadn’t even realized anyone was there until that moment. But the crowd that left, some to the pay phone on the wall, others to the elevators, and still others to the stairwell were younger women and men, mostly of European descent, all I noticed dressed expensively, and Tibetan monks, both ethnically Tibetan and of European descent. They were talking rapidly, mostly in hushed tones. Many were crying.

We all left together swept along by fields of grief and anger and other things that blended together as a back wind pushing us along.

The cacophony told me something terrible had just happened. I was confused there was no lama listed in the census, prominent or otherwise. It wouldn’t be until Monday that I learned what had happened. A disgraced guru who had been one of the most senior converts to Tibetan Buddhism had been there registered under his birth name, Thomas Rich. In those moments we were being told about the girl, he had just died of complications from AIDS.

I can date this event because he is mentioned in articles and books, and significant dates marking his life are recorded for easy research. He died on the 25th of August 1990. The girl, I’m ashamed, I cannot even recall her name. I think about that. This is now just shy of thirty years since that event. That child dying of a heart attack. The mother cursing me, and God. The stream of Tibetan devotees each consumed in their own grief. These images all flow together and haunt me. To this day.

I return to this story. It has been a touchstone for my life. I mention it now and again. If I recall correctly, I reference it in my sort of memoir, If You’re Lucky, Your Heart Will Break.

And I think of that story of the old woman driving off the monk and burning the vacant hut to the ground.

The Zen master Hakuin Ekaku once observed “meditation in action is more important than meditation in stillness.” There are appropriate and inappropriate actions in our lives. Think of it as a dance. And within the dance we all must relate to each other as precious and as valuable as I hope we come to see we are, each of us, as we are. Meditation in action.

Meditation as that burning hut. Meditation as a ring of fire. As the old woman. As that monk who squandered twenty years.

And so here we are. You know. Today. Just as we are. Just in this place. How do we practice? As if the world were on fire. As if the world were dying. As if we, you and I were dying. Maybe a little easier meditation in a time when a deadly virus is sweeping across the globe, people live in isolation, some in relative comfort, others, well, some are flat out on the street. Work has largely shut down. And, people are beginning to be hungry. This today.

A koan is a direct pointing to some aspect of reality, and at the same time is an intimate call to come to that place.

That woman asked the question for her dying daughter. Those monks and devotees asked it for their teacher. Today, right now as we live in various forms of restraint and our economy is slipping probably into a depression. People are isolated. Lonely. Afraid. Bored. Angry.

All of it can be reduced to that word “why?”

And it becomes a koan. And, I suggest, it contains the pointer for that traditional question presented out of the story of the old woman and the monk in the hut and his totally inadequate answer to “how do you feel?”

Of course any koan worthy of the name is actually an invitation into the great mess of our lives. The one we’re living right now.

I believe if we recall that secret of sitting down, shutting up, and paying attention, truths reveal themselves. For one, you and me, just as we are, just as we are. Fleshy and messy. Angry? Lustful? Forgetful? Shy? Aggressive? Name it as yours, know it, really know it. It is the Buddha way presented. Because there is that other thing. All of us belong to the same great boundless family, dying child and her grieving mother, disgraced guru and his distraught disciples. You. Me. One thing, empty, and bright.

A dancing play of the universe. Causes and conditions.

Noticing all this is the first step. From our meditation in silence, then our noticing, if we’re just a little lucky, how each of us in our separate lives are so profoundly connected, so intimate that we can say with only little less than the truth that we are one: then what?

And, so, the question. How will you act out of this place? What is meditation in action? That’s the second step. The necessary second step. Here, with this racing heart. Here, with my own actions and their consequences, it is all revealed.

No place else. There is no other place. As the monk. As the old woman. As the dying girl. As the doctors. As the mother. As the family. As that dying guru. As that confused and lost crowd.

Life as the burning hut. Life as a ring of fire.

As the chaplain sitting with pain and confusion and wonderment.

In the burning of that hut.

Smoke rising.

Smell those ashes.

And feel the sap rising, ready to send out a new branch.

Actually, in my original reflection I ended there. I’m no longer sure, but I think the verse at the end is my own. Although the new branch is an allusion to a slightly crude remark the Eighteenth-century master Hakuin made about the monk’s “old tree,” in some translations withered.

I think of the old woman and what she does after the hut is burned to the ground. I think of the monk. I think of that woman bereft of her child. I think of those who follow in the wreckage wrought by the dead guru.

I think of us, those who will live.

What does all this sitting we have done, those of us who’ve walked the Zen way, or, any of us who’ve walked the varieties of the intimate way?

After we see the moon and know with all our being we and it are not two?

Then what?

I think we each follow our own dharma. We must. But, the word whispers into our ear, and we need to respond. In Nikos Kazantzakis’s incredible novel the Last Temptation of Christ, hanging on the cross his temptation was to accept a way out, to marry Mary and have children and to live to a ripe old age. In the stories of the Buddha, after his great awakening, Mara, the tempter, whispers in his ear that he should now retire to some cave in the remotest reaches and live out is days in quite bliss.

What is our temptation? Yours? Mine? Like for Christ and Buddha, it will be our own.

But it comes. Even as our awakening is found in every moment, the opportunity to turn away arises with it.

It’s hard to judge what another’s calling into the mystery should look like.

I know for me it has something to do with reaching out. Guanyin visits in my dreams and beckons me on.

What about you? In this one precious life, in the light of the full moon, with the smell of ashes hanging in the air, where a killing virus stalks the land, where all things coalesce and it is not one, and it is not two.

Here.

What will you do?