FOLLOWING THE SCENTED GRASSES

A Meditation on Beginnings and Endings and What Happens in Between

James Ishmael Ford

Here we are at an ending. And of course, as such things are, it’s also a beginning.

As to the ending. I thank you for welcoming me into your community, and with that welcoming our Zen sangha to use the church. I love the particular manifestation of liberal and rational religion that is Unitarian Universalism. And you all are the band representing the movement here in Anaheim. I’ve been honored to help keep that flame alive.

iframe width=”560″ height=”315″ src=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/UaxxJXdoph4″ frameborder=”0″ allow=”accelerometer; autoplay; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture” allowfullscreen>

And now other possibilities of service have called me away. And so sorrow and joy wind tight.

But as I go, you all remain in my heart. Absolutely.

I’m grateful for this time.

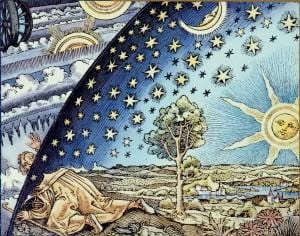

And there’s more to it. Me. In this moment I feel fragile. And there’s power in that. When we are vulnerable possibilities emerge. We stand in a mysterious moment, where, if we attend, we can hear, we can feel secrets about ourselves and maybe even the world. And, I freely acknowledge feeling my heart opening into something. It’s a place you may be familiar with. It is the place where worlds themselves open and the secrets of the universe are on display.

Today I especially find myself thinking of Gary Snyder’s old poem, For/From Lew. Perhaps you know Snyder, one of California’s great poets. Lew Welch was another. On May 23rd, 1971, when visiting Snyder at his home in California’s High Sierras, Welch wrote a note, and then left carrying a Smith & Wesson 22 caliber revolver. His body was never found.

From that Gary Snyder sings into our hearts.

Lew Welch just turned up one day,

Live as you and me. “Damn, Lew” I said,

“You didn’t shoot yourself after all.”

“Yes I did” he said,

and even then I felt the tingling down my back.

“Yes you did, too” I said – “I can feel it now.”

“Yeah” he said,

“There’s a basic fear between your world and

mine. I don’t know why.

What I came to say was,

Teach the children about the cycles.

The life cycles. All other cycles.

That’s what it’s all about, and it’s all forgot.”

Cycles. Endings and beginnings. Here I think about the beginnings that follow endings like night and day.

Solomon sang of these cycles, as well. To every season…

And when I think of seasons, I nearly always find myself thinking of a lovely anecdote captured as case 36 in that Chinese collection of spiritual pointers, the Blue Cliff Record. It’s one of the most important books in my life.

One day Changsha went off to wander in the mountains. When he returned, the temple director met him at the gate and asked, “So, where have you been?” Changsha replied, “I’ve been strolling about in the hills.” “Which way did you go?” “I went out following the scented grasses and came back chasing the falling flowers.” The director smiled. “That’s exactly the feeling of spring.” Changsha, agreed, adding, “It’s better than autumn dew falling on lotuses.”

Endings and beginnings.

Of course it’s not all just you and me and a walk in the hills and a contemplation of spring and autumn. Or, even the burning heat of our moment here is Southern California. The heat of this moment is another reminder, another pointer, if we are willing to let it be so.

After all the world right now is on fire. You may have noticed. The Republic is vulnerable, we can see the cracks in the institutions. And we can’t be sure what will follow in November. And. The planet is vulnerable. We’re watching as climate change is turning up the temperature, and increasingly that world on fire is literal. Through in race and the economy. Well…

These are hard times. And in hard times it can be difficult to see beyond our own personal woes. While it is critical that we do not turn away from the sadness, and particularly the sadnesses we have caused, that’s never the whole picture. We need to look larger.

And. That’s when it can be helpful to notice the cycles.

Really noticing these things can be hard. We’re so caught up in the busy of our lives. Our intimate griefs and joys. It takes something to pull the membrane of our routine thin, and to allow us to see that larger place. We might notice this when, as it is for me right now, so vivid in knowing one of the cycles is coming to an end. And for each of us differing cycles are beginning.

Here we are in the flow of our lives. So many things happening. Each of us following the stars of our own lives. Each part its own cycle. And. There is something special about this gathering, this Sunday gathering, and our returning to it within all the other cycles of our lives. You here. And, now me up the coast a bit to Los Angeles. All these cycles, each following their own rhythms, and each connected.

And its within that context I’ve found myself thinking of that poem Synder wrote for Lew Welch, and that little story of Changsha and his stroll.

As to that book I mentioned with Changsha and the temple director, and their conversation. The book that is one of the handful of most important spiritual guides in my life. The Blue Cliff Record had several editors. Xuedou was the first, gathering the one hundred stories of The Blue Cliff sometime in the eleventh century, and adding a word or two of his own by way of comment. Xuedou’s comments are usually pithy, and often cut through right to the heart of the matter. In fact, as this particular case is published, it includes a little coda from Xuedou. After Changsha’s description of following scented grasses and falling flowers, and the director’s appreciation, and Changsha’s pointed conclusion, Xuedou adds his own: “I’m grateful for this answer.”

Me too. It points us on with a gentle hand. Gentler than most stories from the world’s treasure trove of spiritual teachings gathered by the Chinese Zen masters. But, just as compelling, just as urgent. This story of spring flowers and autumn dew points directly to the secret of our path, the path of the intimate way.

So, what might be the secret that, if we hold it true, makes noticing the turning of spring to summer, of summer to fall, of fall to winter, of winter to spring—of picnics, and walks in the woods, of falling leaves, and of dustings of snow, if for us here seen only on top of distant mountains—all of that stuff, the substance of a spiritual life? I suggest a re-read of Henry Thoreau’s Walden might be interesting in that regard. But, really, this anecdote has all we need.

First, let’s look at the line, “I went out following the scented grasses.” Everything is in flower, as those among us with allergies can attest about that season. The world is alive. We are alive. Notice it. Feel it. Throw yourselves into the moment, not some other moment—this one. For Changsha, it’s a walk in the countryside.

But also, there’s that line about the autumn dew: “It’s better than autumn dew falling on lotuses.” Here we’re also reminded, and really, invited into the cosmic play, found for us as flashes of insight throughout our lives but most commonly noticed when we’re quiet.

We might prefer the scented grasses, but really the autumn dew is just as precious, just as passing, just as beautiful. Each is, or can be our intimation of interconnections so vast, so very vast that you and I—indeed everything we can name—collapses, like a star pulled into a black hole, where even words like “interconnected web,” or, my preferred term, “boundless,” all slightly miss the point.

All this seen within the cycles, ordinary time, and special time, children growing up and assuming their places as adults, ministers coming and going, each of us living and dying in our own time, cycles within cycles. Mind you, cycles, not circles, which are static things and allow no change. Rather cycles are more like spirals, where things change although often in subtle and frequently mysterious ways. Ways we rarely completely notice. Until, of course, they are the way things are. Like ministers coming and going. Seeing the cycles and the larger cycles opens our hearts, reveals the powers of love; reveals love.

That is what we find. That is where we begin. And it is what we return to at the end. It is love that dances within and between and as the cycles.

This is the good news of all authentic religion. It certainly is the good news at the heart of our Unitarian Universalism. It is the universalist message. The vastness of the universe can feel frightening. After all it shows us instantly how insignificant our individual lives are. But, we persist and lean into the vastness, and we begin to notice those cycles connecting it all. And, then, perhaps, possibly, with just the smallest of surrender, we can discover the eruptions of love. We know justice is what love looks like in action. But before that, love is what we discover as we surrender into the great play of what is.

Perhaps you’ve had that taste of reality in all its vastness. It’s a gift to humanity, encountered by rich and poor, by educated and ignorant. Now and then we all catch a moment of its truth, like a flash of lightning in a summer storm. Or, maybe it just haunts an occasional dream.

The point is this: The deep connections that our tradition sings of, the perspective we are all woven together so fine, that we can’t even find our separateness, is an important encounter. I would even call it the God beyond God. But again, words reach, but always, at least in these matters of our hearts, words fail; collapsing into something more than that black hole. For those of us who’ve noticed this experience, we might recognize that description of autumn dew falling on a lotus.

And it is important to notice this big thing, however we name it. It ties us together and puts the lie of our separateness and our sense of isolation to rest. But Changsha adds in something. We find that vastness nowhere but in things—and not things in general—but specific things. The person sitting next to you reveals that whole. Your own experience of this moment manifests the universe itself and the space beyond naming. The whole interdependent web is revealed in a single flower.

We come into this place, we open our hearts, and miracles abound. We see the cycles, we find the mysterious connections as nothing less than love. And from that, from this love, we reach out. Our lives become gifts to other lives.

By attending to what is happening, we notice it. Love. Love like electricity. Love like life-giving blood. It is in noticing the love that connects and binds and enlivens that allows new possibilities to birth. Whole new worlds.

So, again, we must not turn from the sadnesses of the world. We have too much work to do. And, let’s not forget how large the project really is.

Changsha calls us to the world, of the precious individual, of scented flowers. Here, we’re invited to see how that boundless place, that black hole of all ideas and separateness, is also this place. Everything may be tied up together in some great cosmic play that is so vast our words fail to convey it. But it is also nothing other than you and me.

The cycles all joined together. Like garlands of flowers.

Our individual lives like the gift of a flower. Fragile. Beautiful. The dying already in the living.

And, mysteriously, but truly: fully enough.

Fully enough.

This is the lesson of the cycles.

Love reaching out.

Love diving in.

Love.

Amen.