A PILGRIM’S PROGRESS

Zen, Maps of the Spiritual Life, Miscellaneous Traps, and, of course, the Fat Guy

James Ishmael Ford

People take up Zen for any number of reasons. But those who stay find they’re on a spiritual quest. Words like enlightenment and awakening become the holy grail of that quest. Images shift. And we can feel we’re crossing deserts in quest of an oasis with life giving waters, only to find a shimmering mirage on the horizon that quickly disappears as we approach.

Grail. Oasis. Mirage.

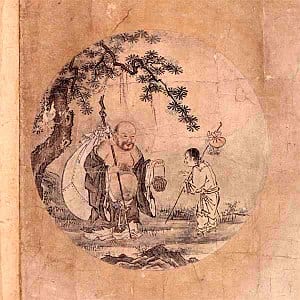

Fortunately, there are maps for this journey. Probably the most famous within Zen are the Ten Ox Herding pictures. They show how a student of the intimate way starts on the spiritual quest, has various encounters of ever deeper insight, passing through, this is Zen, both emptiness and nature, and finally ends up a fat guy carrying a bag of presents into the village.

Of all the images of awakening, Zen’s best-known map presents a fat guy. And that bag of presents.

On my own exploration of the intimate way, I’ve learned a lot from that particular map. But it has gaps. Critically it does not show any of the traps and snares we encounter when we throw ourselves into the intimate way. And, sadly, the way is littered with such traps.

Also, it’s misleading in another sense. The stages of the ten Ox Herding pictures become, well, stages. You pass through one, then another, and finally, eventually you get to be the fat guy.

My problem with this is, well, that’s actually not how it works.

The intimate way is a bit like Elizabeth Kubler-Ross’s famous five stages of grief: denial, anger, arguing, depression, and at the very end acceptance. People also quickly noticed how this list can apply to dying. And. Anyone who has been around grief or dying knows its way messier than that simple arc suggests.

One of the great lessons for me relatively early on, on my way, involved an old friend who died from complications of AIDS. Something rarer now, but in that time simply the end of a progression that did not have alternatives.

I tell this story with some regularity, and if you’ve heard it, I apologize. But I tell because its important. It was important for me. It can be important for you. A friend of my friend came to visit as he was dying and was telling my friend he had missed an important stage on the process. I no longer remember. Anger maybe. Bargaining. Something in the middle. He was quite insistent that it be met. My friend, the dying person said, “You don’t understand. I am the path.” And the insistent friend was not invited back.

Dr Kubler-Ross’s list holds up some incredibly true things we encounter in our lives, especially in hard moments: denial, anger, arguing, depressions, and acceptance. But there is no simple and clear progression. They come in the order they come. Some are revisited over and over, and some, well, some may not be part of a particular person’s path, at all. For most of us we get several at once, and even that final moment, acceptance turns out to be a temporary resting place, to which we come, leave, and, if we’re lucky return to again. And then maybe again.

Now, of the traditional maps of Zen’s awakening, my favorite has to be Dongshan’s Five Ranks. In part because they actually aren’t ranks. They are five faces of the real. Sadly, they don’t include the snares and traps along the way, either. Instead they simply represent differing angles on what in the Ox Herding pictures we see as the Fat Guy. They become reminders who we are as we truly are is mutable, shifting, sometimes a mirage, sometimes the oasis, sometimes a cracked vessel, sometimes the grail itself.

This is also why I am increasingly uncomfortable with the term “spiritual bypassing.” It’s an attempt and an important attempt at addressing the conundrum of spiritual teachers doing bad things. It describes people on the path who miss steps along the way. And because of those missing experiences, they need to go back at some point and address them. Usually these are issues of psychological maturity, or, at least insight into one’s character. And according to the model, if they don’t, they will necessarily be dangerous. Dangerous for themselves. And if they’re teachers, dangerous to others. Cascades of sadness can follow a spiritual teacher who does not see their own shadows.

But the worm in that particular apple is that the premise is wrong. And, well, you know, garbage in… The wrong premise is that supposed map up to the top of the mountain. In the rarified atmosphere at the top, one’s poop should not stink. But that’s not true. It isn’t the way things are.

On the Zen way we’re pointed to the fact that our liberation is nowhere except here. The beginning and the end are in fact not different. In both my observation and my experience, the way does not ascend to Vulture Peak nor to Mt Carmel.

If you want to insist on a direction, it is more downward. It is a journey to depth. Here Enlightenment becomes Endarkenment. It is the way of not knowing. However, even if that bit of geography is less misleading, if we cling to it, it’s wrong, too.

I think the best analogy of the spiritual path is that it is like a game of chutes and ladders.

There is more than an element of chance. You roll the wrong dice and you slide to the bottom. You roll the right dice and you end up at the top. Maybe if your perspective is broad enough you can see all the near infinite variations of the dance of causality and with that “chance” isn’t a good word. But, if you live in the world most of us occupy, it very much looks like you do what you can do, and after that it’s in the hands of the gods.

I started digging around and it turns out “Chutes and Ladders” is the name Milton Bradley gave to an ancient Indian board game called “Snakes and Ladders.” Chutes being less disturbing than snakes for the intended audience.

The origins of Snakes and Ladders or Moksha Patam is lost to antiquity. It’s always a children’s game, the element of pure luck can bore adults. But, it has maybe always had a spiritual side. Hindus, Jains, and Buddhists, and later, Christians, have all used it to teach morality. In the oldest strata it appears to teach karma, desire, and destiny.

According to the Wikipedia article on Snakes and Ladders, the ladders were associated with virtues such as generosity, grace, and success. While the snakes represented vices like lust, anger, theft, and murder. An interesting footnote to it is how more of the one hundred squares behind the snakes and ladders are snakes. The way of virtue is always harder.

The Wikipedia article offers also offers tantalizing sentence for me. “There has even been evidence of a possible Buddhist version of the game existing in India during the Pala-Sena time period.” I looked that up, the period between the eighth and thirteenth centuries. I also found an article about a Tibetan version of the game, “Ascending the Spiritual Levels.”

If you’re concerned about the luck aspect of this, I recall the guidance of several of my teachers that awakening is actually an accident. You can’t attribute any specific cause that precipitates the great eruptions of our hearts. However, our practices make us accident prone.

And, I suggest these practices for us include the great disciplines of meditation, but also the container of an ethical life, for us captured in the sixteen Bodhisatva precepts (remember that spiritual bypassing thing? This is where that needs shoring up.), and, of course, the image of awakening, the thing that is not what you think. The Fat Guy.

And, so, while I’m fond of the Snakes and Ladders model. It ain’t it, either. I suggest if we want a glimpse at our spiritual path to kind of mush up several maps. Today two from two different traditions.

First, those ten Oxherding Pictures. 1) Undertaking the path, 2) Catching sight of some footprints, 3) Having a glimpse of our true nature, 4) Discovering it full, 5) Learning to cultivate the encounter, 6) Riding it home, 7) Dropping all images, 8) Dropping the sense of self at the center, 9) Finding the source, and 10) the Fat Guy.

Each of these are worth endless unpacking.

But, again, they miss some things. And, here I find myself pulled to John Bunyan’s English Puritan spiritual classic, the Pilgrim’s Progress and its sequel which corrects for some serious errors in the first part.

In part one, we find along with that impulse to enter the way, 1) resistance of those around us as we experience the calling of our hearts, 2) Needing spiritual guides, maps and human teachers, 3) noticing false friends, holding onto old truths, and mistaking brass for gold. I recall a reference to someone willing to consider anything, so long as it was sufficiently unlikely.

Then there’s 4) despondency. In earlier Christian mysticism this is called “acedia,” the noon day devil. It is characterized as restlessness, an inability to focus. It can also be experienced as being overwhelmed by our shortcomings and failures.

In 5) we are warned about secularism. For me, this is tumbling into a bare materialism, missing the live animal of our experience. I also think of it as settling for calmness or relaxation in the midst of the activities of our lives. These are not to be disdained. But, there’s silver. And there’s gold.

Here we are wise to 6) look to the ancestors, to familiarize ourselves with the ancient maps and the pointers on the way. At some point we come to 7) various graces, encounters, awakenings. They are blessings on the way. Unless, of course, we hold onto them. They are meant to be experienced, and then let go of. They are intimations of the deep, but if we hold them too tightly, they become false gods.

Actually we encounter a host of traps, 8) The most dangerous of which are getting caught up in the forms, and falling into hypocrisy, letting our outer and inner lives bifurcate. Then 9) avoiding the whispers of failure and, what seems an inevitable tumbling into the dark night of the soul. Here nothing makes sense, and despair rules over all. One can only trudge on as if walking through mud.

And then we encounter our own “last” temptations, each cut to our own shape. In Nikos Kazantzakis’ novel and the film adaptation of the Last Temptation of Christ, Jesus’ last temptation is to come down from the cross, marry Mary Magdaline and live a long and ordinary life. In the Buddhist version, Mara whisper to Siddhartha that he has realized the great insight, and now should just retire to a cave and enjoy the delights of awakening without the messiness of involving himself with the world.

With either temptation, with any temptation, the only solution is to trudge on.

The watchword is always watching. Noticing. Returning.

For us on the Zen way, the 10) trap is experiencing the great boundless, the emptiness of all things, and stopping there.

But if we don’t stop. Then do we come to 11) the Fat Guy.

The second part of Bunyan’s saga reminds us of the holiness of the family and, who would have thought, the sacred feminine. Although perhaps he wouldn’t have thought of it all that way, himself.

Of course, this map comes with its own traps. Again, there is a directionality that is only partially true.

But if we accept these things as maps and not the territory, then, the way is thrown open for us.

We take on our practice, we read the maps, we find guides, and we embark.

Then, as the old joke goes, hilarity ensues. Mystery opens upon mystery. Things mush up, things fall out of order. We discover the end and we find ourselves at the beginning. We discover the mess is for a lifetime. Soup to nuts. Birth to grave. And, as my friend taught me all those years ago, we each of us can discover we are the path.

I am the path.

You are the path. Time and space and all of it a vast interdependent web. Nothing is excluded.

All of it a blessing.

The Fat Guy.

And that bag of gifts.