(My apologies. As I sit with this small essay a couple of days out I realize the problem with it, is that it touches on two related but different issues. The one is my ongoing consideration of Buddhism, and how it is I am a Buddhist, and what that means. I think it a worthy project. And possibly of use to other people. The other is the more intimate exploration. My real time, if you will, encounter with the mystery. At some point I expect I’ll extract the essay about what is my Buddhism. But, for now. This is me…)

Just shy of two weeks ago my spouse suffered a stroke. It was, as such things go, mild. We have every reason to expect a full recovery. But it has left us both shaken.

For me, in my meditations, I experienced moments where the various parts of what I think of as “me” felt especially tenuous. Uncertain past the normal uncertainty that is my Buddhist sense of my self. I could feel those several parts strain to spin away.

And then, just shy of breaking away into the myriad directions I could feel them fall back together. A strange oscillation of my heart. Such, of course, is the experience of not knowing. Not an alien thing. But sometimes more, sometimes less. And, here, now, I am tumbled into not knowing.

As I said, here I am today.

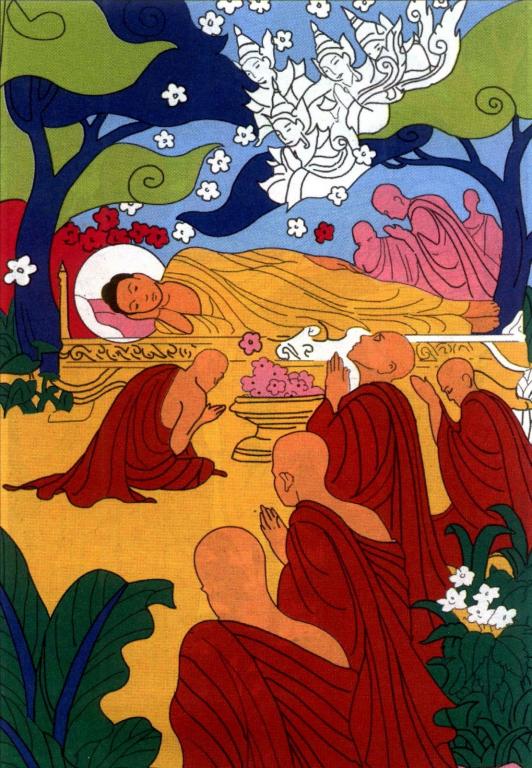

While the majority of Buddhists within the Great Way school observe Parinirvana, the anniversary of the Buddha’s death on the solar 15th of February, some observe the day on the 8th. Today. An apt moment.

Like many ancient festivals, such things as the remembrance of the Buddha’s death or Christ’s birth are movable feasts, the various calendars that are used have changed, many times. And for Buddhism all of this plus the nuances reconciling lunar and solar ways of counting just make it, well, that movable feast…

And. With all of this. Today, I find myself thinking of Nirvana in an anticipatory way, sort of a run up to the holiday. Anticipating Nirvana.

It also shows up the most significant of the various issues that challenge Buddhism in modernity. And more me it is this. There is almost no chance of any post mortem reanimation of any individual. Those parts spilling out, at some point, the do not come back together.

All evidence for rebirth or reincarnation is anecdotal. And the evidence put forth by those who really want such a thing, rarely matches the theological premises that connect rebirths to one’s previous intentions or actions. Kind of like how those who cling to “creation science,” seem to miss, whatever its unlikely truth, it doesn’t support the themes of any of the Abrahamic traditions.

Now my reflection here is not to debate rebirth or reincarnation. Just to note that controversy within the Buddhisms of modernity.

Rather, I am saying that a cornerstone of all modernist Buddhisms, the Buddhisms that take modern science and its methods seriously, whether secular, or, in my case, spiritual or religious (there is no settled language among our as yet dynamic emerging schools) is that the consciousness we currently experience as individuals is the unique product of the coalescence of many things. It emerges out of a moment. And, when those conditions shift, that unique consciousness ceases.

And with that one’s understanding of karma also shifts. In Buddhism traditionally karma is understood as the set of intentions and sometimes actions that result in a next birth. Here karma becomes something that echoes the original insight, but becomes both more specific and more mysterious.

What holds modernist Buddhists as Buddhists, generally speaking are the three marks of existence. That is that everything is impermanent, that there are no abiding substances, and there is an instability in all things that is experienced as suffering. This I experience fully. And, in these moments, if it is possible, more fully.

Up front. Sometimes ugly. Sometimes not. More complex than either of those sentences can convey. For me.

Within the modernist camp there is some divide over the fourth mark, that there is a transformation of experience, an encounter with emptiness that heals all wounds. Here we also find the major divide among many who would call themselves secular and those of us reaching for a best descriptor, spiritual, religious, something…

And, here I stand. In my precious passing moment. Empty of substance. But also very much here. And filled with love and hurt, holding and losing. A roil.

Of course, it comes with a fair question. In Buddhism before modernity our final awakening is called Nirvana. The word is usually translated as extinction. And in the grand story of Buddhism it is the final cessation of the rounds of existence, the many births, all entangled as suffering. Here peace is extinction.

But what happens if there is no round of births? Or, rather that the round is contained within a single biological life. Or, geological. Or, astronomical. Many rounds. Few obviously connected. But cutting to our personal chase. What if the grace of extinction is as cheap as our one death? My wife’s death. My death. What then?

Here on the eve of Parinirvana, the anniversary, more or less, of the ‘Buddha’s death. What does it all mean?

For some it means nothing. Among moderns, I meet people for whom Buddhism is a constellation of practices that militate our hurt. These practices lower blood pressure. And, if one is lucky, maybe there’s a philosophical resolve. Among the more interesting among the emerging secularists is an alignment with Greek philosophical schools such as Stoicism or especially Pyrrhonism. This is interesting and can be rich. And I personally am touched by some of what is being uncovered within that Buddhist/Greek philosophical encounter. Or, as some would have it, re-encounter.

But, I go a step, or, maybe it’s a leap farther.

I am a person of Zen. I have been a student and later a teacher of this way for well past fifty years. I am informed by a period of monastic experience, I am grounded by a discipline of radical presence, and I am constantly schooled by the koan tradition. These things have soaked into my being, all those other things that have been the mix that becomes me.

Koans are the unique contribution to world spirituality of the Zen schools. They emerge in Medieval China and further explored into a style of practice in Japan, taking a shape in the Eighteenth century that has guided me along my way. Not with ever clearer focus, although sometimes it feels like that. But as signposts as I watch the beginnings of the final dissolution of the thing that identifies as me.

The great play of the mystery.

There are many koans, many. But those of us who formally follow curricular koan traditions, it seems we each find ourselves with a small bundle that help us on our way. For this bundle, I’ll appropriate a term used by the Eighteenth century master Hakuin Ekaku. He named a category of koan “nanto.”

I think Hakuin identified eight of the many hundreds he worked through and marked them out as nanto. I find it interested that one scholar seems to have identified ten or so of the eight. And so, we don’t appear to have a tight grasp on nanto koans. Somehow I like that. One Zen master suggested these eight or ten or whatever were particularly hard koans for Hakuin. Suggesting, and it has been my experience, that we each will find our own nanto.

Although in this specific moment, it is one of Hakuin’s traditional nanto that feels most appropriate. I’m thinking of case 38 collected in the Gateless Gate anthology. It goes:

“It is like an Ox that passes through a latticed window. Its head, horns, and four legs all pass through. So, why can’t its tail also pass through?”

Here I find myself thinking of one additional crucial teaching beyond the classic four marks of existence. The two truths of the relative and the absolute worlds. While I fully embrace the teaching of the four marks, it is the two truths that tell me who I am, and how I can find my way through the hurts of this world. It squares the circles and reveals the mystery.

Classically the relative is the phenomenal world, while the absolute is the “higher” truth of emptiness – that lack of abiding substance within the play of causality. In Zen, and in my experience these two things are in fact identical. But even that doesn’t quite work. Because it is a living experience. The least wrong expression I can find for this is not one not two.

And. This is the heart of my Buddhism, the Buddhism that sees the worlds as they are, and invites a great healing. But that healing isn’t found by rejection, by letting go in any sense of renunciation. It is a mysterious passion, that loves things as they are. And in each moment lets them go. Both. And.

For me it’s a bit like that passage near the end of the book of Job. A silence and a whirlwind. Or, it’s “like an Ox that passes through a latticed window. Its head, horns, and four legs all pass through. So, why can’t its tail also pass through?”

I’ve reflected on this case any number of times. It haunts my dreams. And in this moment, in this moment it is on each of my heart beats.

For a dash of background, the question is put to us by the master Wuzu Fayan. I love him. He’s one of those trickster figures about whom we never know quite enough, but he keeps popping up in our lives. Wuzu means “Fifth Ancestor,” but he isn’t the fifth ancestor, who is Huineng. This Wuzu lived through the last three quarters of the eleventh century, dying just at the beginning of the twelfth.

For me he is particularly interesting because the driving question, the heart koan of his life came out of a conversation with a Sutra master whom he asked about awakening. He was told “it is like drinking water and knowing for oneself whether it is warm or cold.” Wanting to know that taste for himself, he launched into the great way. I’ve used that line over and over as the great invitation of the Zen way – to know for our selves, for your self, for my self, what is and what is not.

I consider how in the wake of Jan’s stroke, I could feel the parts of who I am pull away and fall back together. For a moment. It is part of the taste that Wuzu sought. Not big. Not small. But a pointing to the heart. And expression of the heart. A revelation. An apocalypse. A Death. And, a rebirth.

Digging into the koan itself. Clearly in this koan we are given a metaphor. And the metaphor turns on the Ox and the Ox’s tail. It’s fair to suggest this Ox is the same Ox used in that wondrous map of the way of awakening called the Ten Oxherding pictures. According to Aitken Roshi, this Ox “pulls the plow through the mud of the rice fields and enriches them with its manure. Its power and placid disposition give it a place in the Buddhist pantheon with (Manjushri’s) lion and (Samantabhadra’s) elephant.”

In the Oxherding pictures it represents our Buddha nature.

Buddha nature. The mystery. The other thing.The revelation. The apocalypse. The death. And, the rebirth.

It is the invitation of liberation we’re supposed to know so intimately it is like having come to sip that water, and knowing for ourselves whether warm or cool. Here is the flow of cause and effect, where we are woven out of many things, and we ourselves by our actions and intentions add new strands to the great web. It is real. Pinch yourself, and you’ll know it is so.

Like feeling the parts begin to swim away, and then, this time, to feel them swirl back together.

And that place where they come together. The Ox’s tail, if you will.

With that. With all the hurt and longing and loss. With all the joy and love. With the mix of hurt and peace that opens for us in our lives. What about that tail?

Here we also can come back to the Buddha’s assertion of no self, no essence, and at the same time telling stories of lifetime after lifetime that certainly looks like something with an essence. What I find in this is how that emptiness that is as much a part of anything as the thing of it is experienced in our lived lives. We experience emptiness as something.

On my way it has had three manifestations. At least as I parse out what has happened, what is happening, and what I know will happen.

First, there was that separation. I feel it. I know I’m not you. And neither of us is the wall we face in meditation, against which our knowing pushes into unknowing.

Then, through some miracle a noticing realizing viscerally, deeply, truly, that I am connected to you. And you to me. And both of us to, well, everything happening. And with that the Ox’s tail wags at us.

The great emptying? But in what direction?

An interesting question, at least I find it so. So.

Fucking hard. As easy as falling off a log.

Tumbling into that place that is neither one nor two, empty nor full.

Does it happen in our brains? Does it happen in the universe writ large? I have suspicions. But, such things don’t actually matter.

There it is. Here it is.

The third manifestation. A great mystery. Our heart’s revelations. A dance. A song. My spouse Jan sitting across from me reconciling the check book. Me, with our cat insisting on sharing space on my lap with the computer. The light playing its own games of hide and seek. The gentle smell of a dinner soup, split pea tonight, wafting through the room.

All that was. All that is. All that will be. An arc, a spiral, a pulse.

Something I know. And something I can not know. The Ox. And its tail.

The great peace.