THE WORK OF CHANGE

A Zen Reflection

August 22, 2021

Delivered at the

First Unitarian Church of Los Angeles

James Ishmael Ford

I’ve been thinking a lot about changes. And with that the nature of change itself.

In the literature of Chinese Buddhism there’s a lovely little story that hints at some of how we can encounter change in ways that might be helpful. It may not immediately be obvious, but let’s hear it, and then unpack it together, just a little. With that we can consider whether it points us true.

The Zen master Changsha took a walk. When he returned to the entrance of the monastery the head monastic asked, “Teacher, where did you go?” Changsha replied, I’ve come from walking in the hills.” The head monk asked, “And what did you find?” The teacher responded, “I went out following the scents of the grasses, and I returned to the falling blossoms.” The head monastic sighed, “Ah. Spring.” Changsha smiled, “It’s better than autumn dew falling on lotus leaves.” Later one commentator summed the matter up, saying, “Thank you for this.”

I’ve always loved this little story. Changsha lived into the middle of the ninth century, although this anecdote is collected in the thirteenth century anthology of such stories, the Blue Cliff Record, as case 36.

As I think about those grasses and their scents, about autumn dew and those lotus leaves, I find I am invited into the actual lived moments of our lives. The ones that seem in fact to be all about changes. And digging in, all about transitions, those moments when we might notice changes happening, and then what they tell us about who we are.

For a lot of reasons of late I’m finding myself reflecting on all the transitions in my life. Big changes like those shifts from childhood to adolescence to my several adult lives. For me changes through monastery and school and marriage and work. Zen student and then Zen teacher, and of course, blessedly, back to Zen student. And also, very much, the different ministries I’ve been invited into. Each presenting as a moment, but also manifesting rhythms and cycles as well as totally new things.

I’m aware how important moves were to my personal growth as a minister. Each time I was able to pause in the rush, reflect, and incorporate what I learned in previous ministries. In ways we don’t often allow ourselves or are allowed by those around us without something as big as a move, in my case involving crossing the country one way or another several times.

I’m also aware of how congregations have similar experiences of change. Those changes of ministerial leadership, or, giving up or acquiring ministerial leadership, acquiring properties, growing or shrinking membership, lots of things. And each offers moments to become new again. Well, perhaps more insistent than offering.

It isn’t all beer and skittles. Actually, most of the time, change is hard. It might be good. It might be important. It might even be critical. But it is hard. Almost always. This is true whether we’re encountering change as a personal thing or in some communal way.

And maybe that’s a problem with that old Zen story. The image it calls forth for our lived lives are those smells of the grasses and falling blossoms. Certainly evocative. Certainly true. However, sometimes the smell is of a garbage dump. And what falls is putrid. There’s that.

The other part that story ignores, is how most of all we humans really, really like stability, constancy. We don’t like diving into the motion of it all, the shifts and the changes. Most of us, most of the time, we don’t like change at all. And so, we resist. So, there’s that.

And. But. However.

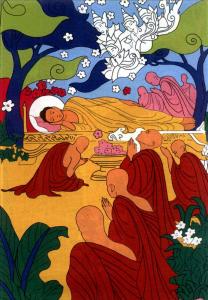

The Buddha of history, Gautama Siddhartha, asserted bluntly our grasping after the permanent is not only folly, it is the cardinal cognitive error. Wishing, or worse, actually believing anything is or can be permanent, is the broad gateway to human hurt. Internally through our desire being constantly thwarted by, well, by reality. Or, outwardly, when people decide they need to enforce their visions of a world not changing onto others. Or to eliminate others that display the ways people do in fact change.

I think of this experience of shifting and changing as the great buzz. Sometimes we encounter it as anxiety. Sometimes it just hurts. Sometimes, it’s even thrilling. Sometimes it’s the smell of wild grasses. Sometimes it’s the smell of puke. It is the great is-ness of our lives.

And, paying attention we find within all this something else is revealed. This is the work of change. It’s one of those big secrets hidden in plain sight. Truth be told, we actually only exist within those transitions. One moment after another. One, if you will birth after another. We are not nouns. We are verbs. We think we’re particles, but we’re waves.

And. But. However.

Even knowing this, when we really do know this as more than an idea, the buzz of that motion for most of us remains an uncomfortable thing. Our whole lives we’re always off balance. The enlightened heart, the awakened heart, doesn’t become something else. It discovers itself, ourselves, as nothing other than this buzz.

How should it be otherwise? After all, noticing change we also notice all things end. And not very well hidden in that is the whisper, you too, I too, will die. All things composed of parts come apart. Look at us in our precious and fragile uniqueness; talk about a composition of so many things. And at the same time those many things themselves are constantly shifting.

I look at who I was as a child, and as an adolescent, and the many different me’s adulting, and except for a constantly evolving geography, my body as a place, and a ghost of a sense of continuity, it is in fact all always shifting, changing, mutating.

We are change.

So, what does the work of change look like?

One bit of wisdom comes to us from Taoism. For ages I was sure this little story was actually one of Zhuangzi’s immortal tales. He’s the guy who told the butterfly story, somewhere roughly five hundred years before the birth of Jesus. I’m sure you’ve heard it. Someone wakes up and realizes they’ve just been dreaming they were a butterfly. Then, a moment of uncertainty as they realized they could just as easily be a butterfly dreaming they’re a human. That guy.

At some point I decided I needed a citation for this story I’m building up to, and looked it up. Not Zhuangzi, it turns out, but that other ancient worthy, anonymous. Whatever, this story certainly conveys the wisdom of the water-course way, and if not by Zhuangzi, by another member of the family. Again, you may well know it. The story goes:

One day a farmer’s horse ran away. His neighbors said, “How terrible.” To which he replied, “We’ll see.” The next day the horse returned bringing along three wild horses. The neighbors said, “Such good luck.” The farmer replied, “We’ll see.” The next day, the farmer’s son fell while trying to tame one of the new horses and broke his arm. The neighbors said, “Such terrible luck.” The farmer replied, “We’ll see.” The next day an army marched through pressing all the young men they encountered into their number. But they left the young man with the broken arm alone. The neighbors said, “Such good luck.” The farmer replied, “We’ll see.”

Just like with the dreaming butterfly, you’ve probably heard this story, too. It’s part of China’s cultural heritage that somewhere in modernity has become part of our collective human wisdom. “We’ll see.” Things happen. Things change. And, well, what’s to be? We’ll see.

It’s of course worth digging a little into the heart of that “we’ll see.”

First, off there’s some good news. While we exist as something constantly changing, we are also in all that motion part of something rather wonderful. Here is the wisdom that is pointed to in the Zen story I cited at the beginning, that part about autumn dew falling on lotus leaves. Better is a bit of a joke, because the image of lotus leaves is pointing to the place out of which we arise, the boundless, and the open. There are no differentiations within openness, only potentialities. No better. And no worse. It is the mystery that is at the very same time all this change that is around us and is us.

So, the work of change. Allowing the open, the boundless as also part of who we are, then we notice a new wrinkle in the mess of things. The truth, as Martin Luther King Jr sang into our hearts, is how “In a real sense all life is interrelated. (We are all of us) caught up in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny.”

I dream of that garment of destiny. I feel in my blood and bones that network of mutuality. It’s not just a good idea, a rather sweet metaphor for some ultimate connection, but a pointer to something we can know it our bones and marrow. It’s why Zen. It’s why all the mystical traditions of the world. It’s the autumn dew. It’s the lotus. Our endless possibility. It is our true nature, which is wild and open and boundless.

I no longer suffer under the delusion there is some magic part of me apart from the mess of life, untouched by causes and conditions, and not subject to change. At the same time, at the very same time, yes there is a thread of self-awareness that calls itself James. Absolutely. I am here. You are there.

Each thing, each you, each me, in its moment is real. But this real is also a dream, gossamer, feather light, floating. And this is so important; that’s okay. It’s all dreams. Butterflies and humans. And puke. And falling blossoms. Dreams all the way down, into that boundlessness. We can enjoy the scented grasses because we know the autumn dew. We are intimate and we are creativity itself.

It is out of this dance of reality that Martin Luther King sings, “Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly. I can never be what I ought to be until you are what you ought to be, and you can never be what you ought to be until I am what I ought to be.”

It’s all intimate. Hurt and joy. So intimate. Longing and love. Intimate. Verbs and nouns. Particles and waves. One thing manifesting in a hundred million, million ways. Intimate.

This acknowledged, known, embraced, I’m not in favor of just sitting back and waiting. It is a “we’ll see” universe, no doubt, absolutely. We need to take time and just notice. The arts of meditation are part of that. But at the very same time we are also called, called by our very lives and our astonishing ability to see and to act to make choices, even when it’s hard. Again, Martin Luther King. “This is the interrelated structure of reality.”

We are what we do. Actions matter. Small and large. Changes are invitations. To, as the philosopher said, pay our money and take our chances. Me, I’m all in favor of trying to put our hands on that arc of history, bending it toward something better. That’s the invitation. That is the moment now. In small ways and large. It’s our work.

And it isn’t easy. As Raymond Chandler’s character observes in the “Long Goodbye,” “To say goodbye is to die a little.” Truth. Absolutely. Change hurts. This work can hurt. And yet. Another Zen line: and yet.

My friend the Zen teacher Mark Strathern notes how the irritant is what makes the pearl in the oyster. How we meet the irritants, how we meet the changes, how we face the flux, well, that’s what makes the pearls of our lives.

The truth be said, we mostly miss how we are connected to the world and to each other. But graced with these moments of change, we can find the ways we’ve become estranged from our lives. This moment of transition, well, it’s an angel appearing, making some wonderful announcement. When we open ourselves to these shifts as the liminal places they are, then, well, magic is in the air.

Change becomes possibility.

The good kind. The kind where we own our lives. And where we put our hands on that fabled arc of history. In small ways and large.

This is where we become who the stars and galaxies named us from before our births.

Dynamic. Open. Connected. Intimate.

That’s the work of change.

Amen.