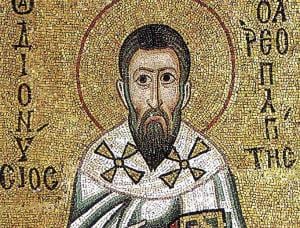

Today, the 9th of October is celebrated in the liturgical churches of the West as the feast of Dionysius the Areopagite. He is venerated in the Eastern churches on the 3rd of the same month.

In the Acts of the Apostles, the second half of the text that we know as the Gospel According to Luke, there is someone named Dionysius who is converted by Paul’s sermon at the Areopagus, a famous rock outcropping at the Acropolis in Athens. According to Eusebius he would go on to become the first bishop of Athens.

Rather more important is that a series of writings appeared in the early 6th century attributed to Dionysius. Modern scholarship has noted the awkward gap of approximately five hundred years between the bishop and the writings, and so usually the author is called Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite. This Dionysius would have enormous influence on the shaping of Christian mystical theology.

For me his approach to a negative or apophatic theology brings him into the large family of spiritual writers that includes many Buddhists. If you regularly read this blog you might notice what follows has appeared before. Or, at least something close. This is one of those reflections that continue to haunt me and which I have trouble just letting be done.

Because, I feel, it’s important…

As the Wikipedia article on the negative way tells us “In brief, negative theology is an attempt to clarify religious experience and language about the Divine through discernment, gaining knowledge of what God is not (apophasis), rather than by describing what God is.” If you substitute “the real” or “what is” or even “sunyata” for the word God, it is possible to find compelling similarities.

And, of course, there are substantial differences. The Pseudo-Dionysius draws heavily on the Neo-Platonic traditions which have little direct commonality with Buddhism. But still. We find the Japanese Buddhist scholar Hajime Nakamura describes similarities between the teachings of Dionysius and Nagarjuna’s Madhyamika Buddhism, seeing the Pseudo-Dionysius’ “super-essential Darkness” as roughly equivalent to Nagarjuna’s “void.” Nakumara goes even farther and suggests some passages in Dionysius’ “Mystical Theology” “might well be called a Christian version of the Heart Sutra.

One of my mentors the Buddhist philosopher Masao Abe was also aware of the deep similarities, as well as the differences between the mystical philosophy of Dionysius and Buddhism, and his own particular focus, Zen Buddhism. Citing this passage from the Mystical Theology:

Ascending higher, we say…

not definable,

not nameable,

not knowable,

not dark, not light,

not untrue, not true,

not affirmable, not deniable,

for

while we affirm or deny of those orders of beings

that are akin to Him

we neither affirm nor deny Him

that is beyond

all affirmation as unique universal Cause and

all negation as simple preeminent Cause,

free of all and

to all transcendent.

As Professor Abe says, “this is strikingly similar to Zen’s expressions of the Buddha-nature or mind.” For me, as one who walks the razor’s edge between East and West, Buddhism as carrying my core theology and Christianity as the body of my childhood and early spiritual formation, this is all so wonderful.

According Dionysius there are three steps to the path of holiness. As a Zen practitioner, I find them a useful if not complete map. Perhaps you might, as well

Writing in his Celestial Hierarchy, Dionysius names these steps, or maybe modes would be a better term, “purifying, illuminating, and perfecting; or rather it is itself purification, illumination, and perfection.” In this he hedges, if I read the line correctly, implying they all are actions, all in a sense, verbs. I have a problem with reading them as rungs on a ladder. That thing about how the matters of the spirit never fit comfortably into boxes or schematics. Fortunately, right at the beginning, I love how St Bonaventure looks at these three steps and says in fact they’re not hierarchical. You don’t go through one and then the other. Each is in fact present at every moment. Steps. Or maybe its modes. That works for me. And at the same time there is something of a staging that does goes on when we decide to take on a spiritual path.

While helpful, it’s all dynamic, and no one should take any attempt at mapping our spiritual path as anything but a rough sketch. And, of course, rather arbitrary. Among later commentators, one of my favorites, Evelyn Underhill reformulates this as five steps, again, or modes, or moments, adding to purification, illumination, and perfecting (or theosis, or deification), the dark night of the soul, and the unitative life. These are maps not the territory.

That said, as a map they do point. There are reasons generations have found them helpful. Including me. With that, a few thoughts on each of these steps or modes.

First, katharsis, purification or purgation. It does feel like a beginning, and in many ways it is. Here we start as we are. I’m fond of that line from Rumi, which I think of as the call to those ready to hear. “Sit, be still, and listen, because you’re drunk, at we’re at the edge of the roof.” Here we notice something is wrong. Whether it is in the world or within our hearts almost doesn’t matter.

If we don’t feel that wrongness, there is no reason to do anything. But, once we do notice, well things happen. That noticing takes a number of different shapes. We can see the hurts inflicted by societies. We can see the dangers inherent in being alive and so fragile. That very fragility can feel a wound, a wrongness. But, as I see it, it requires our noticing at some point some great part of this wrongness has to do with us. You. Me.

Once we see the wrongness, the hurt, we respond in many ways. We may have tried to address it through the actions of the world, drink and drugs, sex, money. But, at some point we see those are not fixes to the hurt.

And with that we launch. Depending on the traditions within which we live this might pull us toward prayer or meditation. For, me, part of the attraction of Zen is how it offers among the most straight forward and practical of practices. At the heart of them all: sit down, shut up, and pay attention.

Here becomes a current for a spiritual life. For me it is the regular returning to paying attention.

Second, theoria, illumination. This is the place of contemplation, where we begin to get a handle on the practices, or rather the practices begin to take hold of us. I like to tell how I once wrote an article on mediation and the publisher commissioned some wonderful illustrations.

However, when it came to the image of the meditator, the figure is sitting, and all around her arrows are pointing out. I wrote back and said my problem with that image is that the arrows are going in the wrong direction.

As Eihei Dogen tells us, “When the self advances toward the ten thousand things, that is delusion. When the ten thousand things advance toward the self, that is awakening.”

They said, oh. And then, that’s too bad. And then they published the article with those arrows aiming out at, well, the ten thousand things. Sort of the way things often are. Including ourselves. I notice we rarely have a good handle on why we practice or even how we practice. We stumble along.

But as we put ourselves in the way of these practices things happen. We might actually, we will almost certainly start by looking out. We begin by advancing, by projecting our ideas on to the things of the world. Of course, there isn’t a ton of success in this.

Here we move into realms where our ideas of what is and what is not begin to crumble. We may have visions. We may hear things. The world itself becomes uncertain. There are traps, snares, a thousand million ways to go wrong. And we persist, we continue to sit, we consult elders, and like water on stone, gradually, gradually, our false sense of self gets worn down. And, if we’re particularly lucky, some fissure in the rock will be revealed, and will at some point by that simple drop, drop, will crack the whole thing open.

But, whether dramatically or so subtly that we can’t even notice something is happening, the shift does occur. The light in fact turns inward. And what we might have thought was our own effort, we begin to notice is only a part of the picture.

And, with that, third, theosis, deification, or union. Here we find the inspiration out of which Meister Eckhart sang “The eye with which I see God is the eye with which God sees me.” Here we are describing the fruits of our practices, of our insights. Here we begin to enter the mystery. What I love about this approach is even this is not a once and forever thing. We may indeed have moments of amazing clarity. Great break throughs. And we may not. And, even the great breakthroughs are not once and forever. They leave a trace, that can indeed inform us, and never be lost. But, that moment is itself a moment.

Once many years ago, I was sitting deep in sesshin, a Zen retreat. I’d arrived in a place of astonishing clarity. And there was a proof to that pudding. I was able to answer koans as if they were children’s riddles. They were each as obvious as the nose on your face. And, I recall the roshi noticing this and leaning in until our noses weren’t more than inches apart. I could smell the black tea he preferred on his breath. He smiled, as I recall wickedly, and said, “James, don’t forget. Even enlightenment is just an idea.”

The beauty of these graces come as reminders of our deep truth. We are in fact not only empty of any specialness, but also connected more intimately than words can ever say.