One of those small wonderments is how the two most important figures in Japanese Zen share the same birthday. Eihei Dogen was born on this day, the 19th of January, in 1200. While Hakuin Ekaku was born on this day in 1686. Dogen would be credited as the founder of the Soto school in Japan, while Hakuin would be credited as reviving the koan way of the Rinzai school in Japan.

They had wildly different personalities, which we can glimpse through their writings. And, each brought amazing gifts to the world treasure house of spiritual wisdom. Amazing people, both of them.

Here I want to quickly remind people of who they were, and then offer the smallest of reflections on how they have come together for some of us and what they have meant in my life and within the broader unfolding of our Western Zen way.

DOGEN

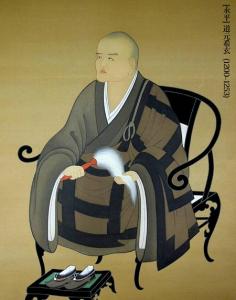

Eihei Dogen was born on the 19th of January in 1200. He is recalled as the founder of the Japanese Soto school (Caodong in Chinese) and as one of the great spiritual writers of all time.

It is believed he was the illegitimate child of an imperial councillor. His mother is believed to have died when he was seven and he was raised within his father’s family.

At thirteen Dogen entered the Tendai order at Mt Hiei. His first teacher was the monk Koen. He is believed to have at least met if not studied with Eisai another Tendai monk who had studied in China and returned authorized to teach Zen in the Rinzai style. Dogen would become Eisai’s heir Myozen’s disciple. With Myozen Dogen delved deeply into the Zen way. And it is likely that it was mostly with Myozen that he became deeply intimate with koans. Certainly his later writings showed a deep insight into their use.

In 1223 Dogen accompanied his Myozen and two other monks to China. There two critical things happened. One is that Myozen died. The other is that he found Rujing, a master of the Caodong school.

While the historicity of the story is debated, Dogen is said to have had his great awakening with Master Rujing. The account is recorded in Keizan’s masterwork the Transmission of the Lamp.

Eihei Dōgen came to Tiantong Rujing. One day, Tiantong said during early morning zazen, “Zazen is body-mind drop off.” Dōgen, hearing this, suddenly had great realization. He went at once to the abbot’s chambers and offered incense.

Tiantong asked him, “Why do you offer incense?”

Dōgen said, “Body-mind drop off.”

Tiantong said, “Body-mind drop off. Drop off body-mind.”

Dōgen said, “This is a momentary achievement. Don’t confirm me too hastily.”

Tiantong said, “I do not confirm you hastily.”

Dōgen said, “What is this not-hastily-confirming?”

Tiantong said, “Body-mind drop off.”

Dōgen made bows.

Tiantong said, “Drop off body-mind.”

At that time, his attendant Huangping of Fuzhou said, “It is truly not a trifling thing for a foreigner to attain to such a degree.”

Tiantong said, “Before he came here, he received the blows of many fists. Liberated is he is mild and peaceful. The thunder roars.”

Dogen would return to Japan and while he professed a nonsectarian Zen, in fact he called what he taught simply “the Buddha way,” he is acknowledged as the founder of the Japanese Caodong school, using the Japanese pronunciation, Soto. He was a prolific writer and some of his writings are considered among the great spiritual treasures of world culture.

But Dogen’s greatest gift was articulating the mysterious action of practice/enlightenment, what we tend to call zazen, seated Zen, or shikantaza, just sitting. Here’s a wonderful article that points to the complexities and possibilities Dogen presented to us.

Dogen died on the 22nd of September in 1253.

HAKUIN

Hakuin Ekaku was born on the 19th of January, in 1686, in a village at the foot of Mount Fuji. He would become the great reformer of Japanese curricular koan Zen.

Hakuin Ekaku was born on the 19th of January, in 1686, in a village at the foot of Mount Fuji. He would become the great reformer of Japanese curricular koan Zen.

As a child he attended a lecture given by a Nichiren priest on hell. The talk captured the boy’s imagination. He became obsessed with the idea of the hell realms. And he determined to escape them by becoming a monk.

When Hakuin turned fifteen he entered the monastic life as a Zen priest at Shoinji. Soon after he was sent to study at a neighboring temple, Daishoji. Here he delved deeply into Mahayana texts, and in particular he studied the Lotus Sutra. Ultimately he dismissed it as recorded in Wikipedia, as “nothing more than simple tales about cause and effect.”

Hakuin continued training and ended up at Zensoji. Here he became obsessed with the story of Yanto Quanhuo, a Chinese master who when murdered by robbers yelled so loudly that he could be heard valleys away. He despaired of ever escaping hell and while not formally disrobing, deciding to devote himself to literature and poetry.

When he was staying with the poet monk Dao Rojin he saw a stack of books about all the schools of Buddhism. He prayed to be directed to the right path, and reached with eyes closed to pick a book. It was about Zen.

At the age of twenty-three Hakuin had his first taste of awakening, hearing the ringing of the temple bell. He dug into koans with Shoju Rojin, who pushed him through three major awakening encounters. While he did not receive formal authorization from the master, he forever considered Shoju Roshi his master, and his contemporaries as well as history see him as the master’s heir.

Something happened, a medical or psychological crisis. He called it a “Zen sickness.” He ended up finding help with a Daoist hermit. And, from that period he included attention to health, what I think we would consider both physical and mental, a part of his practice.

At the age of thirty-one Hakuin returned to Shoinji where he had originally been ordained, and accepted the invitation to become the head priest of the temple. He would serve for fifty years.

About ten years into his abbacy, Hakuin was reading the Lotus Sutra, which he’d long before dismissed. And in a chapter on parables, where the Buddha warns against attachment to one’s personal awakening, and described the Bodhisattva way, returning from the mountain, and serving until all cross to the farther shore together, he awakened into the truth of the words.

He declined invitations to the capital and other larger institutions, instead staying at his original temple.

Hakuin taught that there were three essentials to the practice, great doubt, great faith, and great energy. His attention to the koan way would lead a reform of how Japanese Zen approaches the discipline, becoming two styles named for grand successors of his Inzan and Takuju. (My own koan life is itself a slight modification of the Takuju system) He encourage both monastic and householder practice. For a bit longer reflection digging into some of the art and heart of his teaching, I recommend a brief reflection by Roshi Dosho Port.

He would eventually authorize eighty dharma successors. And today nearly all Rinzai lines trace through him.

Hakuin was also a prolific writer. One of his enduring works is his Song of Zazen.

(Translated here by Norman Waddell)

All beings by nature are Buddha,

As ice by nature is water.

Apart from water there is no ice;

Apart from beings, no Buddha.

How sad that people ignore the near

And search for truth afar:

Like someone in the midst of water

Crying out in thirst,

Like a child of a wealthy home

Wandering among the poor.

Lost on dark paths of ignorance,

We wander through the Six Worlds,

From dark path to dark path–

When shall we be freed from birth and death?

Oh, the zazen of the Mahayana!

To this the highest praise!

Devotion, repentance, training,

The many paramitas–

All have their source in zazen.

Those who try zazen even once

Wipe away beginning-less crimes.

Where are all the dark paths then?

The Pure Land itself is near.

Those who hear this truth even once

And listen with a grateful heart,

Treasuring it, revering it,

Gain blessings without end.

Much more, those who turn about

And bear witness to self-nature,

Self-nature that is no-nature,

Go far beyond mere doctrine.

Here effect and cause are the same,

The Way is neither two nor three.

With form that is no-form,

Going and coming, we are never astray,

With thought that is no-thought,

Singing and dancing are the voice of the Law.

Boundless and free is the sky of Samádhi!

Bright the full moon of wisdom!

Truly, is anything missing now?

Nirvana is right here, before our eyes,

This very place is the Lotus Land,

This very body, the Buddha

Hakuin died on January the 18th, 1769.

COMING TOGETHER

These two teachers are terribly important in my own life. Words fail as I try to express my debt.

My initial Zen practice was within Dogen’s inheritance, and I would eventually be ordained a Zen priest within his lineage. His approach to the intimate way, washed through the generations, would become the formation of my spiritual life. What I hope is the mature shape of my spiritual practice was provided through Hakuin’s inheritance. I spent twenty years investigating the intimate way through a reformation of curricular koan practice which follows in a straight line back to Hakuin.

(A small footnote: For many years I assumed the formal lineage that transmitted my koan practice was Soto. However, I am now convinced I actually received Hakuin’s lineage at the completion of the formal part of my koan studies.)

What is most important are the gifts of practice that I was given through the lineages of these two teachers. I was ordained and received dharma transmission from Koun Jiyu Kennett in Dogen’s lineage. And I studied the intimate way of koan introspection with and received inka from John Tarrant within Hakuin’s lineage. They gave me my life. That I received authorizations through both these lines have also given me a terrible obligation, to foster and to share them.

I have passed this combined line on to several people. They are Melissa Blacker, Edward Oberholtzer, Douglas Phillips, Dosho Port, David Rynick, and Jay Weik. Barry Farrin is a teacher in a closely related lineage who I fully ordained, Dosho Port is a dharma heir to the Soto master Dainin Katagiri, to whom I passed on the koan lineage, and David Rynick had previously received full authorization in the Korean lineage transmitted by Master Seung Sahn. I also gave full transmission to Josh Bartok and Lanny Ross, both of whom have since disrobed and ceased to teach. And I’ve given denkai the first step of transmission to Desmond Gilna and Tetsugan Zummach. I am currently working with three apprentice koan teachers, Maurine Weinhardt, Thomas Wardle, and Janine Larsen. Given my age and the time it takes to train teachers, it’s unlikely there will be others who form their teaching lives with me. Although one never knows. Already several of my earlier heirs have trained and authorized heirs of their own.

What will follow out of this work, who knows. While our karma is bound up together, and each of us with Dogen and Hakuin, how this will play out is hidden within the mists of unfolding time and space.

But, whatever else is true, the offerings of Dogen & Hakuin have come West, as individual lineages, and in a couple of cases, like with me (and on a larger scale within the White Plum, which brings the same koan lineage somewhat enriched and a different Soto ordination transmission).

Today on the the strangest of continents, Turtle Island, Dogen and Hakuin are walking together, hand in hand.

What blessings they may bring are still to be determined.

But, I am so grateful. So grateful.

Endless bows…