The Buddhist Temple of Toledo & the Future of Zen in North America

This past weekend I flew out to the Midwest to attend two events in Toledo.

One was to join as a witness to the denbo ceremony (full dharma transmission) of Karen Do’on Weik.

The other was the dedication ceremony for the new temple building for the Buddhist Temple of Toledo on Saturday, the 23rd of April, 2022. It was a wonderful event. Somewhere in the vicinity of two hundred people were present. There were even television crews from two local news programs. It is a big deal in that area. And, I believe, when I think about the state of Zen in North America, the West generally, and East Asia; I think it a significant marker.

As we face the consequences of the greying of North American Zen, what I’ve called variously the Great Die Off, or the Great Collapse, (I notice others are now using these terms and realize I should have trademarked them) many of us who’ve given the greater part of our lives to the Zen project wonder what will follow.

As we face the consequences of the greying of North American Zen, what I’ve called variously the Great Die Off, or the Great Collapse, (I notice others are now using these terms and realize I should have trademarked them) many of us who’ve given the greater part of our lives to the Zen project wonder what will follow.

When I visited this dedication in Toledo, I felt I was seeing one of the more exciting possibilities.

There are a few things to notice in the run up to the Great Collapse. Zen as a recognizable thing here in North America dates to the early decades of the Twentieth century when the Japanese missionary Reverend Hosen Isobe established temples in Honolulu, San Francisco, and Los Angeles. But it didn’t really cross over to the general population until the 1950s. From that point it took off and would become a current within our broad Western religious scene, and a signal part of the counter culture that arose in the 1960s and early 1970s.

There are a few things to notice in the run up to the Great Collapse. Zen as a recognizable thing here in North America dates to the early decades of the Twentieth century when the Japanese missionary Reverend Hosen Isobe established temples in Honolulu, San Francisco, and Los Angeles. But it didn’t really cross over to the general population until the 1950s. From that point it took off and would become a current within our broad Western religious scene, and a signal part of the counter culture that arose in the 1960s and early 1970s.

Teachers from Japan, Korea, Vietnam, and China would all come to live in the West and present the unique forms of their cultural expressions of Zen Buddhism. People from North America and Europe would also go to Asia to train and return as teachers. And, soon people would train in North America and become teachers.

Teachers from Japan, Korea, Vietnam, and China would all come to live in the West and present the unique forms of their cultural expressions of Zen Buddhism. People from North America and Europe would also go to Asia to train and return as teachers. And, soon people would train in North America and become teachers.

For various reasons few of these teachers would be tightly tied to the institutions of their Asian communities, and the North American Zen landscape would be left free to develop along the lines envisioned by their founding teachers. Or, at least equally so, and perhaps in fact more commonly, as the vagaries of time and event dictated.

Today there are temples tied closely to immigrant communities that attempt to foster the cultural religious expressions of their home countries. They continue and among them there are very interesting evolutions. Among the converts there are a couple substantial lineage families, principally evolved from the work of early missionary teachers Shunryu Suzuki, Taizan Maezumi, and Seung Sahn. Between them their dharma descendants claim the larger part of the North American Zen scene, creating what I’d call the normative forms of Zen in North America. At least teaching what most people think of as Zen.

Today there are temples tied closely to immigrant communities that attempt to foster the cultural religious expressions of their home countries. They continue and among them there are very interesting evolutions. Among the converts there are a couple substantial lineage families, principally evolved from the work of early missionary teachers Shunryu Suzuki, Taizan Maezumi, and Seung Sahn. Between them their dharma descendants claim the larger part of the North American Zen scene, creating what I’d call the normative forms of Zen in North America. At least teaching what most people think of as Zen.

Beyond them there are numerous other lineages. Most notable would be that established by Thich Nhat Hanh. His is a Buddhist vision with a Zen component but more eclectic than what many here consider “Zen,” deeply shaped by the unique vision of that teacher. It tends to follow its own trajectory. Among the other “smaller” lineages there is considerable divergence in the focus of their teachings. Some are very exciting. Some are quite worrisome.

This is not meant to establish a comprehensive list of the lineages in the West. But noting the principal communities have been derived from Japanese Soto, the lay koan reformed movement sometimes collectively called Harada Yasutani Zen, and the reformed vision of Korean Zen master Seung Sahn developed. For good and ill.

Me, I’m not by nature a polemicist. But I read some of the rants about the state of Zen here on social media and often find within the outrage issues with which I share concern. An astonishing large amount of Zen in the West seems concerned with a zazen unconnected to the project of awakening.

Me, I’m not by nature a polemicist. But I read some of the rants about the state of Zen here on social media and often find within the outrage issues with which I share concern. An astonishing large amount of Zen in the West seems concerned with a zazen unconnected to the project of awakening.

Mostly this arises out of the Japanese Soto lineages. At the same time there is a sort of back to Japan movement among both Soto and Rinzai derived lines that feel authenticity is only going to be found in a rigorous transmission of their specific lineage tradition with as few accommodations as possible.

Out of my years as a participant observer I feel we are fully inside that curse of “interesting times.” I also believe blessings travel quite closely with the curse of interesting.

In my view the principal purpose of the Zen project is awakening. I take it a step closer to the bone: Zen is about awakening. I can’t say I’m uninterested in Zen expressions that don’t emphasize this, my associations with the Soto derived communities are too long and too deep to repudiate the don’t worry about awakening, just sit, just do the rituals, and with it an ancient romance with the monastic life, without a word of appreciation. That just sitting, that just doing the rites, can be, and occasionally is an expression of awakening. But, as I see it, the gift of Zen is a path to awakening, and to the integration of insight. Everything else is upaya.

But what this needs to look like is not found, in my view, by turning back to East Asia. With full gratitude, with many bows, with respectful acceptance of the core gifts; we need to make this project our own. By “we” I mean the children of Turtle Island, North America, and the West. With our mixed history, with our dynamic and dangerous moment in time. The we that has arrived here and now.

Among the things I consider necessary givens for an authentic Zen in the West is an assumption of the equality of people as full practitioners beyond categories of sex and gender expression. I consider it necessary to embrace people who are not going to be monastic as fully authentic Zen practitioners, and should circumstances lead that way, as teachers.

And, I believe it necessary for communities and their leaders to be mindful of the ways in which people are included or excluded. That is, I believe Zen in the West, if we hope for it to succeed, must find accommodations with the society within which we live. And, to be engaged in appropriate ways. Appropriate is, of course, a messy word.

And, I believe it necessary for communities and their leaders to be mindful of the ways in which people are included or excluded. That is, I believe Zen in the West, if we hope for it to succeed, must find accommodations with the society within which we live. And, to be engaged in appropriate ways. Appropriate is, of course, a messy word.

The people who I most admire on the Zen way are largely focused on the project of awakening. Most are not especially interested in the social component, and even on occasion denigrate it as distracting. I respectfully suggest they’re missing several points. First, awakening is not separate from our lives. And this includes both personal lives and social lives.

Personally I wonder about the value of awakening that can only be found within a monastery. And, second, but intimately connected, the transmission of the tradition cannot be separated from finding accommodations within the larger culture. This includes paying attention to the raising of children.

Okay. All that is the background.

Then there is the thing I encountered on the 23rd of April, 2022.

I see a new vision emerging. I would say it sees fairly clearly that for Zen to root here it has to pay attention to two things. Waking Up. Absolutely. Totally. Focused. And. Growing Up. That is all those things that make us better people and members of our communities.

A mature Zen practice needs to attend to waking up and to growing up. How they do it in Toledo offers a pretty good road map to how this might look. They exist as two closely touching, significantly overlapping, but also separate projects.

The first is what is emerging as a pretty normative version of Zen practice, which instead of being monastic, is retreat driven. Lots of retreats of various lengths, but rarely if ever exceeding seven days. These retreats are intensive and they’re meant to punctuate lives of regular daily practice. For Toledo the thread that runs through them is what is often called the Harada Yasutani koan curriculum, rooted in the Takujo Hakuin system, but adapted in ways that make it uniquely transferable to the West.

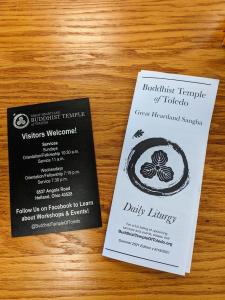

But this is not seen as complete by itself. And, so there is the second aspect, what I’ve called the “church,” and what they call the temple. This is a place for people to come, patterned not on East Asian temple life, but on Western religious patterns circling around a Sunday service which includes educational opportunities for both adults and children. Emphasis on children.

Kids are welcome at the temple. Their noise and disruptions are seen as positive things, and are embraced. Also, they’re not ashamed of being Mahayana Buddhists. Some are Jewish or Christian, many consider themselves as nonreligious. Their doors are open, and open wide. But the temple is a Buddhist temple.

They offer a positive vision of the world, and are inclusive. And they’re engaged. They are aware of social evils, and while reluctantly, and with hesitation, and with reflection, they take communal stands on the issues of the day. Informed by their understanding of Zen Buddhism as a way to live in this world. They present as whole people a whole life.

Not to exaggerate. They’re people. The lack of racial and ethnic diversity is perceived as a wound and a shortcoming. They are aware of class issues and who can participate and who cannot. They see themselves as a work in progress.

Pretty amazing. Truly amazing.

At the dedication of the temple I noticed two particular things. Among the two hundred or so people present, half were under forty. And, it was a long service, and not the most kid-friendly event, but there still were at least a half dozen younger kids present.

Bottom line. Zen, it turns out, is alive and flourishing in the American Mid West.

If you want to see what Zen in the West can look like in the next several decades, look at Toledo.