A student of the intimate way asked Zhaozhou, “Why did Bodhidharma come from the West? Zhaozhou replied, “The Cypress Tree in the Garden.”

Gateless Gate, case 37

I cannot say what a treat it was when I was offered the chance to review a new book from a California based publisher, Kales Press. I love smaller presses, and I especially am happy to see California based publishing.

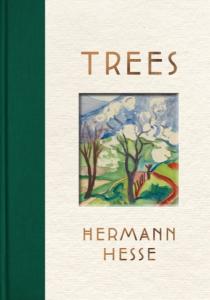

The book:

Trees: An Anthology of Writings and Paintings

by Herman Hesse, translated by Damion Searls, and selected by Volker Michel.

Hardcover | cloth

5 x 7 inches | 136 pages | 32 full-color watercolors painted by Hermann Hesse

ISBN-13: 978-1-7378327-1-3

Price: US $28.00 | Nature

May 2022

The truth is these days I usually decline such offers. But this was something from Herman Hesse. And that caught me. From a small press here in California was frosting on the cake. Hesse is one of the icons of my reading life. His books opened the door for me on my own Eastward walk. Or, at least helped to open that door.

As it happens he became available to North American readers in popular editions in the late nineteen sixties and early seventies. Which was at just the right moment for me, as I was beginning to find the shape of my spiritual life. Actually, even the order in which I read his books accompanied me in critical ways in my spiritual formation.

So, as I said. Icon. Important. Very important.

If you’re not familiar with him, Hermann Karl Hesse was born on the 2nd of July, 1887, in the Black Forest in Wurttenberg. Through his father he was automatically both a subject of the German and Russian empires.

Hesse’s religious upbringing was Pietist. While technically Lutheran, Pietism was in fact an amalgam of Lutheran and Reformed Protestantism. Between this theological stance, his mixed cultural inheritance, and a life long inclination toward what used to be called melancholia and is now diagnosed as depression, Hesse always felt something of an alien among his own. This sense of outsiderness would mark his spiritual life, and maybe even drove it.

His family included theologians and ministers. His father Johannes, was a publisher specializing in theological writings and textbooks. His grandfather Hermann, a missionary, polyglot and the creator of a Malayalam grammar, encouraged Hesse’s intellectual curiosity and gave the boy free run of his large library. His mother Marie, shared her love of music and poetry with him.

While in school he had a nervous breakdown and attempted suicide. He was briefly institutionalized. Soon after this he concluded his formal education and became an apprentice at a bookstore. Within weeks he quit and took up an apprenticeship at a clock tower factory. This didn’t work either. He then returned to the book trade. While working at a bookstore he began a long period of self-directed study reading mostly theology, philosophy, and mythology.

In 1896 Hesse published his first poem, and then a slender collection of poetry, Romantic Songs. It and his second book both were commercial failures. His third book received positive notices and it led to a contract for the novel Peter Camenzind. This novel was a best seller in Germany. Sigmund Freud praised it lavishly. And with its success he left the book trade to became a full time writer.

Financially established he married Maria Bernoulli and began a family. And his writing continued.

Spiritually Hesse became interested in Buddhism, Schopenhauer and theosophy.

With the onset of the First World War he entered the army, but due to physical ailments was considered unfit for combat. However beyond a desire to serve, he was not caught up in the war hysteria. He wrote an essay reminding everyone of their common European heritage. It was met with controversy, and he received a lot of hate mail. Soon after his father died and his wife Maria was diagnosed with schizophrenia.

Hesse then entered psychoanalysis with Carl Jung. A critical turn in his inner life.

With his wife institutionalized, Hesse obtained a divorce, farmed his children out, and moved to Switzerland. He remarried, twice. First to Ruth Wenger, then at the age of fifty to Ninon Dolbin.

While he condemned the Nazis and specifically denounced anti-Semitism, and helped some people fleeing Germany, he has been criticized for otherwise largely ignoring the travails of the Second World War. All along he continued to write. After the war Hesse enjoyed a revival in Germany. In 1946 he was awarded the Nobel Prize for literature. Hesse died in 1962. He was survived by Ninon.

Of course the truly important part of Hermann Hesse for me is his interior life. Looking at the arc of his life one can see him growing ever more eclectic spiritually. I don’t believe he ever actually abandoned Christianity, although what he meant by that word certainly shifted over the years. He is quoted as saying “For different people, there are different ways to God, to the center of the world.” I find that last clause, “the center of the world” intriguing. Perhaps I caught that sense, perhaps not. But, there was nothing in his writings that required belief, certainly not belief in a creator deity. And that was important for me.

He also asserted that in finding God or the center of the world, “…the actual experience itself is always the same.” While I would say the words we put to that experience are wildly different, to my mind colored as it must be by culture and temperament, there is also a great pointing in that “always the same.” It has both cautioned and pointed for me.

Putting it all together Theologian Christoph Gellner wrote, “(I)n the course of his lifelong investigation of the phenomenon of religion, he developed the notion of a synthesis between the religions on the basis of a universal mysticism. He was, in fact, seeking the unity of all peoples, a connecting bridge between East and West.” Gellner continues, “Hesse believed in a ‘religion outside, between and above confessions, which is indestructible.’ Yet he always took a very sceptical view of dogmas and teachings. ‘I believe one religion is as good as the other,’ he writes. ‘There is none in which one could not become a sage, and none in which one could not just as easily engage in the most inane form of idolatry.'”

As I said Herman Hesse was critically important for me. I first stumbled on Damien when I was working in a bookstore myself. It’s description of a spiritual journey caught my imagination, and underscored my own path. While I couldn’t identify with the privileges of the protagonist’s middle class life, his struggles felt exactly my own.

I then read Siddhartha. I have to admit it never moved me as much as it did many of my other friends. But I very much enjoyed that spiritual pilgrimage as well. Siddhartha’s encounters with that other Siddhartha, the Buddha, echoed my own journeys into Buddhism, and, I don’t know, maybe foreshadowed things for me.

It took me three goes to read Steppenwolf. Perhaps the fact the protagonist was older than me, where both those earlier novels had clearer anchors for my youthful identification made it harder at first. I don’t know. But it provided another angle on the spiritual journey. And as I’ve grown older it has continued to seep into my bones.

I loved the Glass Bead Game, particularly the “three lives” section appended to the end. The complexity of the spiritual life, and particularly the story of the hermit renowned for piety, but who is consumed by self-hatred goes in quest of another spiritual director, only to find he had also been looking for the protagonist.

But, most of all, it is Journey to the East that haunts me. I read it soon after Narcissus and Goldmund, which I found bloodless – all archetypes. And I nearly stopped. But, Journey was short and I picked it up. And read it.

And at the end, what can I say? My own journey continues. And Hermann Hesse continues with me on this journey.

Then I was given the opportunity to revisit this old friend and mentor.

Trees is a lovely book, wonderfully curated by Volker Michels, generally considered the foremost authority on Hesse. His selection touches on Hesse’s essays and poems, and particularly draws us to one of the great images of the human imagination: trees.

The translator Damion Searls specializes in literary works in European languages. Among the authors he has translated are Marcel Proust and Ranier Maria Rilke. He also previously translated Hesse’s Demian. Searls is the recipient of numerous awards. Most recently he has been shortlisted for the International Booker Prize for his translation of a Jon Fosse novel.

All wonderful. What makes this volume particularly wonderful in my view are the thirty-two watercolors by Hesse.

And. I led this little review off with a reference to a famous koan, anthologized in two great collections, the Gateless Gate (case 37) and the Book of Serenity (case 47).

The question about Bodhidharma is a traditional trope, asking what is Zen? And rather more to the point, what is the fundamental matter? What is truth?

Zhaozhou, one of the great teachers of the tradition responds to this burning question of so many lives and says “Cypress tree in the garden” In another version the tree is an oak. I rather like that the tree is itself a bit slippery.

The wonderful Zen teacher Nyogen Senzaki tells us how “Zhaozhou’s response is obviously gentle, but it contains a secret power that can steal away all your delusions before you recognize it.”

I suggest taking a little time with Herman Hesse’s Trees. You may well find in the words and especially in the paintings direct pointers on your own journey.

Right into the heart of the matter.