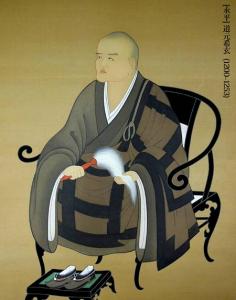

Eihei Dogen died on this day, the 22nd of September, 1253, in Kyoto. He was fifty-three.

And. Oh, my. What he accomplished in those fifty-three years…

In his magisterial study, Dogen’s Manuals of Zen Meditation, Carl Bielefeldt begins by telling us “The Zen school is the Meditation school, and the character of Zen can be traced in the tradition of its meditation teaching.”

As most people interested in the matter know, the word Zen is the Japanese pronunciation of the Chinese word Chan, which itself is the Chinese pronunciation of Dhyana, which literally means concentration but is understood to mean meditation. Zen is a school of Buddhism devoted to meditation.

No doubt Zen offers a richness of training possibilities beyond that practice. But at the heart of the matter is meditation. This discipline that is Zen meditation has evolved from classic Buddhist meditation associated with Gautama Siddhartha. It comes to us starting with Vipassana or “insight,” and Samatha or “concentration.” But, it is washed through the whole of Chinese culture with some influence by way of Confucian culture and more from Daoism. And perhaps even more important it is infused with the great insight of our original awakening. It becomes a unique gift of the Zen schools.

The practice of Zen meditation is sometimes called mokusho, or “silent illumination, “or shikantaza, “just sitting.” In his essay the “Method of No Method,” the Chan master Sheng Yen writes:

“This “just sitting” in Chinese is zhiguan dazuo. Literally, this means “just mind sitting.” Some of you are familiar with the Japanese transliteration, shikantaza. It has the flavor of “Just mind your own business.” What business? The business of minding yourself just sitting. At least, you should be clear that you’re sitting. “Mind yourself just sitting” entails knowing that your body is sitting there. This does not mean minding a particular part of your body or getting involved in a particular sensation. Instead, your whole body, your whole being is sitting there.”

I’ve also found my great grand teacher Hakuun Yasutani also gives a very helpful pointer.

“Shikantaza is the mind of someone facing death. Let us imagine that you are engaged in a duel of swordsmanship of the kind that used to take place in ancient Japan. As you face your opponent you are unceasingly watchful, set, ready. Were you to relax your vigilance even momentarily, you would be cut down instantly. A crowd gathers to see the fight. Since you are not blind you see them from the corner of your eye, and since you are not deaf you hear them. But not for an instant is your mind captured by these impressions.”

The principal document for many of us comes from the thirteenth century Soto Zen master Eihei Dogen’s wonderful Fukanazengi. It comes to us in two versions. The first is a very early publication dated from 1233, although clearly based on thoughts dashed off earlier. Carl Bieledfeldt suggests the second edition appears to date from 1243, a decade after his first attempt. There are other editions and it is hard to say what should be considered the definitive version.

The text is based on a Chinese document, the Zuochan yi written by Changlu Zonze which dates from the beginning of the twelfth century. Although Dogen is critical of that original manual and definitely brings his own stamp to the matter. And by his second version, the so-called vulgate version, he is presenting his mature understanding of the practice.

And here’s where I might be considered a bit controversial. As I read the text in both versions I see the matter of just sitting, of shikantaza being presented as a koan. For me its as plain as the nose on your face and the critical key to understanding Dogen’s manual.

Let’s look at the text.

FUKANZAZENGI

(Translated by Norman Waddell & Masao Abe)

The Way is originally perfect and all-pervading. How could it be contingent upon practice and realization? The Dharma-vehicle is utterly free and un-trammeled. What need is there for our concentrated effort? Indeed, the Whole Body is far beyond the world’s dust. Who could believe in a means to brush it clean?1 It is never apart from you right where you are. What use is there going off here and there to practice?

A means to brush it clean is an allusion to the famous verse contest by which the Sixth Zen Patriarch Hui-neng received the Dharma transmission from the Fifth Patriarch Hung-jen. The verse of Shen-hsiu, Hung-jen’s chief disciple, was: “This body is the Bodhi tree; the mind like a bright mirror on a stand. Constantly strive to brush it clean. Do not allow dust to collect.” Hui- neng responded with the verse: “Basically, Bodhi is not a tree. Neither does the mind-mirror have a stand. From the first there is not a single thing, so where can dust collect?” (CTL, ch. 5).

And yet if there is the slightest discrepancy, the Way is as distant as heaven from earth. If the least like or dislike arises, the mind is lost in confu- sion.2 Suppose you gain pride of understanding, inflate your own achievement, glimpse the wisdom that runs through all things, attain the Way and clarify your mind, raising an aspiration to escalade the very sky. You are making an initial, partial excursion through the frontiers of the Dharma,3 but you are still deficient in the vital Way of total emancipation.

Look at the Buddha himself, who was possessed of great inborn knowledge—the influence of his six years of upright sitting is noticeable still. Or Bodhidharma, who transmitted the Buddha’s mind-seal—the fame of his nine years of wall sitting is celebrated to this day. Since this was the case with the saints of old, how can people today dispense with negotiation of the Way?

You should therefore cease from practice based on intellectual under- standing, pursuing words and following after speech, and learn the backward step that turns your light inward to illuminate your self. Body and mind will drop away of themselves, and your original face will manifest itself. If you wish to attain suchness, you should practice suchness without delay.

For the practice of Zen, a quiet room is suitable. Eat and drink moderately. Cast aside all involvements, and cease all affairs. Do not think good, do not think bad. Do not administer pros and cons. Cease all the movements of the conscious mind, the gauging of all thoughts and views. Have no designs on becoming a Buddha. The practice of Zen (sanzen) has nothing whatever to do with the four bodily attitudes of moving, standing, sitting, or lying down.

At the place where you regularly sit, spread out a layer of thick matting and place a cushion on it. Sit either in the full-lotus or half-lotus posture. In the full-lotus posture, you first place your right foot on your left thigh and your left foot on your right thigh. In the half-lotus, you simply press your left foot against your right thigh. You should have your robes and belt loosely bound and arranged in order. Then place your right hand on your left leg and your left palm facing upwards on your right palm, thumb-tips touching. Sit upright in correct bodily posture, inclining neither to the left nor the right, leaning nei- ther forward nor backward. Be sure your ears are on a plane with your shoulders and your nose in line with your navel. Place your tongue against the front roof of your mouth, with teeth and lips both shut. Your eyes should always remain open. You should breathe gently through your nose.

Once you have adjusted yourself into this posture, take a deep breath, inhale, exhale, rock your body to the right and left, and settle into a steady, unmoving sitting position. Think of not-thinking. How do you think of not-thinking? Nonthinking.4 This in itself is the essential art of zazen.

The zazen I speak of is not learning meditation. It is simply the Dharma-gate of repose and bliss. It is the practice-realization of totally culminated enlightenment. It is things as they are in suchness. No traps or snares can ever reach it. Once its heart is grasped, you are like the dragon when he reaches the water, like the tiger when he enters the mountain. You must know that when you are doing zazen, right there the authentic Dharma is manifesting itself, striking aside dullness and distraction from the first.

When you arise from sitting, move slowly and quietly, calmly and deliberately. Do not rise suddenly or abruptly. In surveying the past, we find that transcendence of ignorance and enlightenment, and dying while sitting or standing, have all depended entirely on the strength gained through zazen.5

Moreover, enlightenment brought on by the opportunity provided by a finger, a banner, a needle, or a mallet, the realization effected by the aid of a fly whisk, a fist, a staff, or a shout, cannot be fully comprehended by human discrimination.6 It cannot be fully known by the practice-realization of supernatural powers.7 It is activity beyond human hearing and seeing, a principle prior to human knowledge or perception.

This being the case, intelligence, or lack of it, does not matter. No distinction exists between the dull and sharp-witted. If you concentrate your effort single-mindedly, you are thereby negotiating the Way with your practice-realization undefiled.8 As you proceed along the Way, you will attain a state of everydayness.9

The Buddha-mind seal, whose customs and traditions extend to all things, is found in both India and China, both in our own world and in other worlds as well. It is simply a matter of devotion to sitting, total commitment to immovable sitting. Although it is said that there are as many minds as there are people, all of them must negotiate the Way solely in zazen. Why leave behind your proper place, which exists right in your own home, and wander aimlessly off to the dusty realms of other lands?10 If you make even a single misstep, you stray from the Great Way lying directly before you.

You have gained the pivotal opportunity of human form. Do not let your time pass in vain. You are maintaining the essential function of the Buddha Way. Would you take meaningless delight in the spark from a flintstone?11 Form and substance are like dewdrops on the grass, destiny like the dart of lightning—vanishing in an instant, disappearing in a flash.

Honored followers of Zen—you who have been long accustomed to groping for the elephant—please do not be suspicious of the true dragon.12 Devote your energy to a Way that points directly to suchness. Revere the person of complete attainment beyond all human agency.13 Gain accord with the enlightenment of the Buddhas. Succeed to the legitimate lineage of the patriarchs’ samadhi. Constantly comport yourselves in such a manner and you are assured of being a person such as they. Your treasure-store will open of itself, and you will use it at will.

Devote your energy to a Way that points directly to suchness. Revere the person of complete attainment beyond all human agency.13 Gain accord with the enlightenment of the Buddhas. Succeed to the legitimate lineage of the patriarchs’ samadhi. Constantly comport yourselves in such a manner and you are assured of being a person such as they. Your treasure-store will open of itself, and you will use it at will.

As I read Dogen over and over again its obvious how deeply informed he is by koan introspection. It isn’t totally clear what the nature of his koan training was, and when he was studying was a transitional period where the huatou form of koan introspection was beginning to include study of lists of koans. However, writing as a person following a koan path it seems obvious Dogen is deeply informed by the koan tradition, and not merely as a reader of Zen anecdotes. A koan informed insight is present on every page he writes. And sometimes, I believe, it would be difficult to understand him if one is not familiar with the koan way.

However, the master is also critical of a one-sided koan practice. He was especially harsh with those who get lost in the sky castles that shadow the koan project. That said in the Fukanzazengi he tips his hat to the koan way, informing us how “enlightenment brought on by the opportunity provided by a finger, a banner, a needle, or a mallet, the realization effected by the aid of a fly whisk, a fist, a staff, or a shout, cannot be fully comprehended by human discrimination.” He gets engaging koans as a leap beyond form and emptiness. Of that there can be no doubt.

But, instead of those many koan Dogen points us to one. First he tells us, “The practice of Zen has nothing whatever to do with the four bodily attitudes of moving, standing, sitting, or lying down.” So, it isn’t simply a matter of assuming a correct posture. Rather he is inviting us elsewhere. Then he tells us where. “The zazen I speak of is not learning meditation. It is simply the Dharma-gate of repose and bliss. It is the practice-realization of totally culminated enlightenment. It is things as they are in suchness.”

This is what he calls practice-enlightenment. In fact I’ve seen that term rendered without the hyphen, simply reading practiceenlightenment. One word. One thing. In some ways it is taking up the koan of just sitting as if it were a huatou, the single koan one needs for a lifetime of engagement.

What I am sure of is this. You want a classic koan? Show me practiceenlightenment.

Here we’re invited into something beyond a mere quietism. And, of course, that’s the shadow of the way of just sitting. People “proof text” the term and warn against “gaining-mind” with unfortunate consequences. We are not being invited into being bumps on some log. Although, sadly, I’ve seen people think that is precisely what shikantaza is.

I offer an alternative understanding. With shikantaza we’re given a place to put our great questions, our deep curiosity, our profound longing. Here we’re being invited into a mysterious alchemy of the heart. Yes, gaining-mind does not carry us across the river. And, it is no different than our awakening.

The mystery of bodhicitta, our desire for awakening is discovered as we experience it, and as we surrender it. But, this isn’t surrender in the sense of burying it or throwing it away. Rather it is a transformation into confidence, or trust, or maybe the right word is faith. Here we discover faith as a matter of heart, as an invitation into an ancient love. Master Taizan Maezumi tells us,

“When you do shikantaza, have faith in the fact that your zazen is the same zazen as the zazen of the Buddhas and Patriarchs. Have this kind of faith. Then, just sit. Since your zazen is the same zazen as that of the Buddhas, you don’t need to worry about anything: just sit. Appreciate that your zazen is the zazen of the Buddha. The zazen of Shakyamuni Buddha is okay; the zazen of the Buddhas and Patriarchs is okay. In other words, you are not sitting; Buddha is sitting.”

If we bring our full selves to the matter, we find something breaks open. Well, sometimes breaks open. Sometimes unfolds like a flower. The images both liberate and trap. We must walk carefully. Gently. And fiercely at the same time. And so Dogen charges us to “Devote your energy to a Way that points directly to suchness.” And, critically he tells us how. “If you concentrate your effort single-mindedly, you are thereby negotiating the Way with your practice-realization undefiled. As you proceed along the Way, you will attain a state of everydayness.”

So, if its a koan how do we engage shikantaza?

Dosho Port, a contemporary Western Zen master tells us about his introduction to shikantaza and his introduction to koan introspection. “Katagiri Roshi’s initial instruction was to become one with the breath and Tangen Roshi advised me to begin muji (the Mu koan) by becoming one with Mu.” Within our discovery of oneness with all things are revealed, all gates are opened.

Just be present.

A koan is an assertion about reality and an invitation to intimacy. What does practice-enligthentment mean? What is nonthinking? Here the koan is to sit down and become Buddha. The state of everydayness. The koan way. The great Zen way.

Just this.

Notes to Waddell & Abe’s translation:

1. The Whole Body [of reality] (tathata ̄) refers to the totality of things in their suchness; the Buddha-nature. The world’s “dust,” giving rise to illusions, defiles the original purity of the Buddha- nature.

2. From the Zen verse Hsinhsinming: “If there is the slightest discrepancy, the Way is as distant as heaven from earth. To realize its manifestation, be neither for nor against. The conflict of likes and dislikes is in itself the disease of the mind. . . . Do not dwell in dualities, and scrupulously avoid pursuing the Way. If there is the least like or dislike, the mind is lost in confusion.”

3. Dharma (hô 法): Truth, Law, the doctrine and teaching of the Buddha, Buddhism. Through- out this translation, “Dharma” refers to Truth, and “dharma(s)” refers to things, the elements of existence, phenomena of your mouth, with teeth and lips both shut. Your eyes should always remain open. You should breathe gently through your nose.

4. These words appear in a dialogue that Dôgen makes the subject of SBGZ Zazenshin: A monk asked Yüeh-shan, “What does one think of when sitting motionlessly in zazen?” Yüeh-shan replied, “You think of not-thinking.” “How do you think of not-thinking?” asked the monk. “Nonthinking,” answered Yüeh-shan.

5. According to the Zen histories, Bodhidharma and the Fourth, Fifth, and Sixth Chinese patriarchs died while seated in zazen. The Third Patriarch died standing under a large tree.

6. These are allusions to the means that Zen masters use to bring students to enlightenment. Chü-chih’s “One-finger Zen” is the subject of Case 3 of the Wu-men-kuan. When Ananda asked Kashyapa if the Buddha had transmitted anything to him besides the golden surplice, Kashyapa called out to him. When Ananda responded, Kashyapa told him to take down the banner at the gate, whereupon Ananda attained enlightenment. The Fifteenth Indian Zen Patriarch, Kanadeva, paid a visit to Nagarjuna. Nagarjuna, without saying a word, instructed an attendant to place a bowl brimming with water before his guest. Kanadeva took up a needle and dropped it into the bowl. As a result of this act, Nagarjuna accepted him as his disciple. One day when Shakyamuni ascended to the teaching-seat, the Bodhisattva Monju (Manjushri) rapped his gavel to signify the opening of the sermon, declaring, “Clearly understood is the Dharma, the royal Dharma. The Dharma, the royal Dharma, is thus,” words usually uttered at the close of a sermon. Shakyamuni, without saying a word, left the teaching seat and retired.

7. The supernatural powers (jinzû 神通) are possessed by beings of exceptional spiritual attainment, enabling them unrestricted freedom of activity, eyes capable of seeing everywhere, ears of hearing all sounds, and so on. Dôgen says that the means used by a master in bringing students to enlightenment are not only beyond human thought, they are also beyond such super- normal powers. Moreover, there is nothing mysterious or supernatural about it; it is normal, every- day activity.

8. Since negotiating the Way (practice-realization) in zazen is practice-realization of ultimate reality, it is beyond all the defiling distinctions and dualities arising from conscious striving.

9. This is an allusion to a dialogue between Chao-chou and his master Nan-ch’üan. Chao- chou asked, “What is the Way?” Nan-ch’üan said, “Your everyday mind, that is the Way.” “Well, does one proceed along it, or not?” asked Chao-chou. “Once you think about going forward, you go wrong,” replied Nan-ch’üan (CTL, ch. 8).

10. An allusion to the parable of the lost son from the Lotus Sutra. An only son left his home and family to live in a distant land. He experienced great hardship, totally unaware of the increas- ing wealth his father was accumulating in the meantime. Many years later, the son returned home and inherited the great treasure that was his original birthright.

11. Spark from a flintstone is a metaphor often used to describe the brevity of human life.

12. An allusion to the well-known story from the Nirvana Sutra of a king who brought an elephant before a group of blind men and had them touch different parts of it. When he asked each of them to describe the beast, they gave widely diverse answers due to the limited nature of their individual experiences.

The true dragon is an allusion to a story in the Latter Han History about a man named Yeh Kung- tzu who had a passion for dragons. He had paintings and carvings of dragons throughout his house. One day a real dragon, hearing about Yeh’s obsession, descended from the sky to pay him a visit. It poked its head through Yeh’s front window, scaring him witless. Dôgen is insinuating that the Japanese of his time, ignorant of the true Dharma, had acquired a passion for false teachings. He tells them that now that he has brought them the real Dharma, they should not doubt its truth.

13. Since zazen is the practice of total reality, everyone who engages in it is a “person of com- plete attainment beyond all human agency” (zetsugaku mui nin 絶学無為人), a descriptive phrase from the Cheng-tao ko.