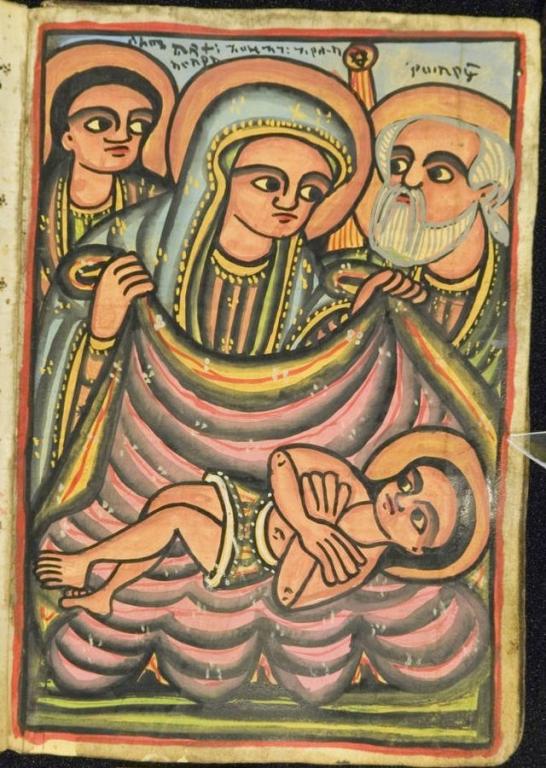

Alwan Codex

Ethiopian Biblical Manuscript

THE FOURTH CHRISTMAS SERMON

A Zen Vision of a Christianity that Is and Might Be

James Ishmael Ford

Christmas Day. Today is Christmas Day.

I rummaged through records of my quarter century of parish ministry and since, what now, seven full, and pushing on eight years preaching around and doing some consulting as I circle toward actual retirement. I reviewed what I’ve kept about Christmas. It appears I have three sermons, or, technically sermon subjects as I can’t actually bear anything I’ve written in the past, and keep hoping the next time I might get it right. So, three sermon patterns…

I really like the sermon about how at least in New England, but ifn many ways in the early iterations of the United States, it was the Unitarians (with an assist from the Episcopalians) who salvaged Christmas. The holiday had functionally been banned by New England Puritans, who quite correctly saw it was deeply rooted in pagan holy days. It had also fallen out of favor in the general English population for various reasons. In American Puritan world if Christmas fell on a Sunday, it was to be ignored. If Christmas fell on any other day, it was officially a fasting day. Any other observation of Christmas was liable to a fine. We Unitarians did a good job saving the holiday. By the bye, we even introduced the Christmas tree to America. Great sermon.

The second sermon was how Charles Dickens made our modern understanding of Christmas as a turn to care and attention, and, well, economic justice. Again, a signal feature of this sermon in its several iterations is that while Dickens floated from being a nominal Anglican through a personal friendship with a Unitarian minister came into the Unitarian fold. Although when that friend died, he drifted back to the warm and light embrace of the Church of England. However, and most importantly, his novela, A Christmas Carol, was written in the years he was attending the Unitarian chapel. Love that sermon.

The third sermon turns on what is called the Christmas Truce. It celebrates a minor bit of passive resistance on the Western front in the First World War, which at the time was called the Great War, and to our tastes terribly ironic, War to End all Wars. In 1914 English and German troops paused in the battle, crossed no man’s land, shared drinks and sweets, and even played a bit of soccer together. It lasted until the higher ups put a stop to it with threats of executions to follow. I’ve long felt it an important sermon.

But what about today? Christmas, 2022. A hard year, following several hard years. Frankly, we’re not looking toward anything especially promising in the “good will to all” area of things. I’m not completely historied out. But I am more interested in what might be useful to us, today. I’m wondering what my fourth Christmas sermon might be.

I really do love Christmas. Those three sermons are each a part of it. But I beliver there’s something a bit deeper to be found. Something that informs a minor rebellion among combat troops, that informs Dickens’ wonderful reframing of the holiday. Something inspiring the reclamation of the holiday by early Nineteenth century American Unitarians. Connected. And profoundly. But, maybe deeper, something of the universal heart available for us today. Today, in these hard times.

What I think of as the text for today’s reflection is a quote from my favorite Jewish Buddhist poet/song writer/performer, the late Leonard Cohen. It comes from a 1988 interview.

“I’m very fond of Jesus Christ. He may be the most beautiful guy who walked the face of this earth. Any guy who says ‘Blessed are the poor. Blessed are the meek’ has got to be a figure of unparalleled generosity and insight and madness… a man who declared himself to stand among the thieves, the prostitutes and the homeless. His position cannot be comprehended. It is an inhuman generosity. A generosity that would overthrow the world if it was embraced because nothing would weather that compassion. I’m not trying to alter the Jewish view of Jesus Christ. But to me, in spite of what I know about the history of legal Christianity, the figure of the man has touched me.”

First. The main thread of the Christian religion is about the idea that Jesus is God, who incarnated as a human being, and then sacrificed himself as atonement for the sins of humanity. The sins that actually condemn us, each and every one of us, to eternal punishment, are inherited from the disobedience of our original ancestor. People who believe this are saved from eternal punishment following our physical death, and instead with death are reborn into an eternity of joy. With that there’s a bottom line. What you do doesn’t matter. What you believe counts for everything. The shorthand for this religion is “Preaching Christ Crucified,” or, perhaps an “Easter Christianity.”

Now, this is the religion of people I love. And as I think about it, I find that Easter Christianity can itself be engaged two different ways. Well, two, at least. In matters that go deep there seem always to be another way to approach than what we think are the outer limits. But of my two. There is the literal version. The one I just outlined. This is the religion preached by every fundamentalist preacher on television. There are variations among some, like Catholics, who say there is a place for what we do in the scheme of things.

There is a bottom line to the narrative which aligns pretty closely for all mainstream, Easter oriented Christianity. Mainstream. Normative. Important words. This is what most Christians are expected to believe. The creeds all point to this religion. Again, the religion of people I love. And I wouldn’t hurt them for the world.

But there is a second way of engaging the Easter story. Think of it as a minority report. But I know it’s taught by a lot of Christians, especially Anglicans and many mainstream Protestants. I’ve heard Catholics speak of it as well. And actually, you can even see threads of it among the Orthodox. It’s about the human heart. It’s internal, psychological, spiritual. And that version has some compelling aspects to it. I think it may even inform those who hold to the story in that most literal of ways.

My friend the UCC minister John Mabry describes a version of this Easter oriented Christianity, that certainly touches my heart.

“Once upon a time God was desperately in love with his creation. The fact that there was distance between himself and his creation was deeply painful to him. He wanted to be close to it, as close as a lover. After thousands of years of thinking about it, he took the leap. He emptied himself of all of his power and merged with his creation, taking the form of a vulnerable infant. And in so doing, he became one with everything, an act that changed him and creation forever. For not only did he enter the whole of creation, but he brought all of creation into himself. Now there was no separation between himself and his creation. All was…and is…One. As the Athanasian Creed put it, through that infant God and humanity became One ‘not by conversion of the godhead into flesh but by the taking of humanity into God.’”

I do notice this softer more internal understanding, this mystical sense, this nondual Christianity, is loudly refuted by the literalists. And, actually, as I see it, that Athanasian creed which gives my friend that lovely line about identity, is actually one of those texts that really want to drive home a literalist understanding. More than the other historic creeds it tries hard to define some obscure theological terms.

Literalism seems a human thing, something very hard to get beyond. Possibly part of why I’ve noticed some among today’s hard atheist crowd want to insist the only “real” Christianity is that hard literalist version.

Literalism is the backbone of the larger project of all religions, all “isms” actually. Which is, to say it kindly, all about cultural reinforcement. These stories tells us who belongs and does not belong to our group, our tribe, our people. I don’t say such a thing isn’t important. But I don’t believe it is anywhere near most important. The matters of our hearts, of noticing the wounds and separation that live at the core of our being, and the seeking of that healing, of some secret call to return, to the source, to the one, is never touched by literalism.

And, interestingly, neither the history of Christianity, nor its founding texts necessarily support a literalist Easter Christianity. The history is a mess. Looking at it from where we are today, we can see how each transition moment leading to the religions we understand as, well, normative, felt inevitable. But at the time. On the ground. Not necessarily at all. It’s just what happened. And all along the way there’ve been minority reports.

Everyone can cite scripture to prove their point, pretty much whatever that point might be. The good, the bad, and the just plain weird of appealing to the scriptures alone. For instance, as regards Jesus, the canonical gospels paint four different pictures. In Mark we get someone who might be a prophet in the sense of the older Hebrew scriptures, with a strange and haunting ending to the story. One that so bothered early scribes that they added a more satisfactory ending.

In Matthew we get a messiah, but by messiah someone more aligned with the traditional Jewish understanding of the word as a king or military leader; although, absolutely with a twist. A bringer of justice, although not as a king or general, but as one of the poor.

Luke adds in some hints of divinity into the narrative. It is, after all, written by a disciple of Paul who seemed to be all in for Greek mystery religions.

Only in John, in all likelihood, written three or four generations after Jesus died, is he a god in human skin. Without that fourth gospel, it would be very hard to create an Easter Christianity.

If one wants to add in the gospel of Thomas, while noncanonical it is the only surviving text that actually dates from the time the accepted books were put together, its final version dating from about the same time as John. Well, we get one more Jesus. This one looking less like a god or a traditional Jewish messiah, and much more like a Zen master.

Easter Christians, actually both the literalists and the more internal path Christians, like to say you have to take it all together. I’ve tried that on. Partially out of respect for my natal tradition, partially as a mind experiment. But when I do, I still don’t find their Christianity. I don’t see a story about how to personally live forever, and the devil take the hindmost. Or certainly not in any literal sense.

The isolated part of me that I call James dies. This being of bone and meat, when it returns to the elements, that’s it. Period. This is the way of all flesh. Souls as some benign passenger in the boat of flesh, makes no sense to me. I guess it arises from our noticing how living beings animate. And comes with speculations about when the animation ends. Heaven and hell in some versions of Judaism, certainly in Christianity and its sibling Islam. Reincarnation or rebirth in the Dharmic traditions. From where I sit, there is no compelling reason to believe this other than a wish to not die. Two and a half millennia ago the Buddha taught this sense of an isolated self was not only a cognitive error, but that clinging to it was the primary gateway to human suffering. I look at this world, and I believe that is a harsh and dreadful truth.

Nonetheless, there is also that connection thing. Which, well, it doesn’t die. It was never born, and it never passes away. For us as human beings this is the grand intuition, an intimation which we can find for ourselves as a deep experience of what that connection thing, what intimacy really is. Within the stories of religions, it sings to us how we, you and I can actually encounter this truth, not as a nice idea. But as a perspective known down to our bones and the marrow within our bones. Here is a good news. Our sense of isolation is in fact a dream. In this sense, a delusive dream. The good news of the mystical threads in, as near as I can tell, pretty much all the religions, is that we can wake from this dream of isolation, into that world of connections, into an intimate way.

The religions that matter to me, or currents within those religions, are what can guide us into this place. The teachings that show us what an awakened life might be. What the earliest followers of Jesus called their religion: the way. A way of intimacy.

As I live with and into the stories of Jesus, his words and actions as contained in the scriptures, me, I find Leonard Cohen’s Jesus, the strange, and wonderful, the compelling, and yes, a bit mad, leaping out of the pages. Breaking the chains of those who would make him some Greek mystery divinity. And instead, showing forth someone, something truly wonderful. And singing into our hearts about what we and this world might be.

“Any guy who says ‘Blessed are the poor. Blessed are the meek’ has got to be a figure of unparalleled generosity and insight and madness… a man who declared himself to stand among the thieves, the prostitutes and the homeless. His position cannot be comprehended. It is an inhuman generosity. A generosity that would overthrow the world if it was embraced because nothing would weather that compassion…”

For me this is the truth that some call nonduality. It doesn’t mean we’re united in some vague spiritual otherness. It means there is in some very real sense no separation. And, in seeing that profound connection, noticing how it draws our hearts to the lost and left behind. Why when Mary is told she will be the mother of God, her song is about the rich and the poor, and how God is going to be found. In Zen we speak of not one, not two. Here we see the connections and the specifics of those connections as lived lives.

People work hard to make Jesus not poor. Listen to those prosperity preachers sometime. They have a boatload of followers. And there are more sophisticated versions for those want to nuance it a bit. Only good things happen to those who believe. But. Here’s a harsh truth. They’re lying to themselves as much as to everyone else. It speaks to fear, it speaks to the fragility of our lives, those of us who have something. And who fear losing it. Losing ourselves.

And. But. So. Here’s my fourth Christmas sermon. Emanuel means God with us. The Christmas story is that story. It is about how we can find the connections as human beings. If we’re willing to let go of our certainties, of our clinging, of our knowing it all. If we can let go of our wealth, of our distractions, of our certainties. If we can let go. And follow the intimate way. Then we can see what drew the wise men. Then we can see what drew the shepherds. Then we understand why the angels sang. It is where our healing is going to be found.

And so. Here we are on Christmas Day. We know the history. We’re standing in the Solstice season, in the midst of a great turning. It is a pregnant moment between what was and what is to be. Here I think a lot about the Christmas Jesus. The human Jesus, born poor among the poor. But also, and at the same time, in the dream world, if you will, something more. After all there are several kinds of dreams. And some dreams tell us the truth. Here surrounded by angels and wise men, as well as shepherds and peasants. The person who grew to become the good rabbi, who called us to a new world. This world that is something partially in the future, and maybe the past, but is mostly, most importantly here and now. His message was, best I can see, an apocalyptic call to reject greed, and hatred, and the illusion of separation. A bit crazy. A lot wonderful.

My fourth Christmas sermon. Maybe the most important of them.

Today is Christmas. It comes in hard times. It comes in these times. Here, I dream of what might be birthing into this world. What might come with all the difficulties and challenges and hurt and longing.

I dream an ancient dream of a good that heals. I dream of Christmas miracles. And the work of Christmas. Very much I dream of the work of Christmas. Which is to find ourselves in the birthing of a child.

You and I are not separate, not in ways that matter in the deepest sense. That intimacy we find within ourselves and among ourselves, is God, is heaven, is the Pure Land. Knowing it we discover our hands bring bliss and healing. It’s that simple. And it is good news.

So, friends, in that spirit, let me be among the first today, to say Merry Christmas!

Amen.