THE UNITARIAN WHO WOULD BE PRESIDENT

A Meditation on the Politics of Unitarian Universalism

A sermon delivered at

the First Unitarian Church of Los Angeles

5 February 2023

Back in the day, most people with an axe they were looking to grind regarding candidate and then President Barack Obama, wanted people to know he really was a Muslim. You know. Some kind of other. But there were a few people who wanted to keep a little closer to the facts. And those people made sure we all knew Obama was in fact a Unitarian Universalist. Which they said, in case it wasn’t totally obvious, meant he was a communist.

As they say, close enough.

At least for President Obama there’s an argument to be made. I mean about the UU thing. His maternal grandparents were Unitarian Universalists, and he spent a goodly part of his childhood in their care. There are plenty of people who can recall young Barack in the children’s program at the First Unitarian Church of Honolulu. As most of us know his adult faith journey eventually took him to more normative forms of Christianity. Of course, that path he followed didn’t hurt his political prospects. You know, the UU means communist thing.

There were in fact four Unitarians to hold the office of the presidency. Two most of us like. John Adams and later his son John Quincy. But also, Millard Fillmore, whom most of us would just as soon forget. And William Howard Taft. He is not generally ranked high on the list of American presidents. But he did enjoy the distinction of later becoming the tenth Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. Having served as both president and chief justice is a unique distinction.

Some people like to add in Thomas Jefferson. And in his later life he wrote nice things about the Unitarians. But he never belonged to a Unitarian church and is by most reckonings counted as a Deist. As a footnote there has never been a Universalist president. Although I read an interesting article that argues that the needs of the office tends to create a “presidential universalism.” Very much lower case “u,” however.

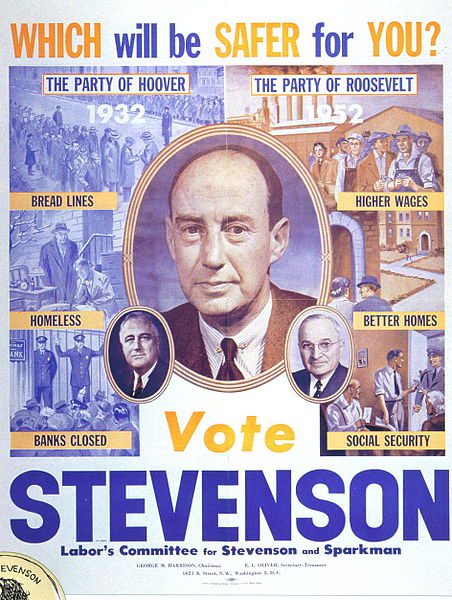

The last Unitarian to mount a credible campaign for the presidency was Adlai Stevenson. He was born on this day, the 5th of February, in 1900, in Los Angeles.

The grandson of the 23rd vice president of the United States, and eventually governor of Illinois, Stevenson carried the Democratic banner twice in presidential elections. First in 1952 and then in 1956. Both times he was defeated by Dwight David Eisenhower. In 1961, the year the American Unitarian Association and the Universalist Church in America consolidated to form the UUA, John Kennedy appointed him ambassador to the United Nations. Four years later he was serving in that capacity when he died of a massive heart attack while walking in London, England.

Stevenson was a fascinating figure. His mother was a Unitarian and a Republican. His Father a Presbyterian and Democrat. He would later say “I wound up in his party and her church.” Which he added, “seemed an expedient solution to the problem.” He occasionally attended the Presbyterian church, and even briefly was a member of one of their congregations. When asked about this he said only because there was no Unitarian option at the time. He never was not a Unitarian and for those last four years of his life, interestingly for the duration of his tenure as the American ambassador to the United Nations, he was a Unitarian Universalist.

Stevenson was brilliant and quick with a quip. When the Unitarian Universalist Association was formed in 1961, he sent a letter to Dana McLean Greeley, the UUAs first president, saying “Congratulations on your election as president. I know from hearsay how satisfying that can be.”

As an intellectual in an era not particularly cherishing such, there’s a famous story where a reporter told him, “Governor, you have the vote of all the thinking people.” To which he replied, “That’s not enough. I need a majority.” While the term “egghead” for an intellectual is not so common anymore, in my childhood and youth it was a common disparagement. In fact, the term was coined by the newspaper columnist Stewart Alsop to describe Stevenson, who in addition to his prodigious intellect was also balding and had a pronounced high forehead. Kind of like an egg.

In some ways I see Adlai Stevenson as a turning figure, representing the shifting from Unitarianism as a part, if a bit nearer the edge, of the American mainstream. Unitarian Universalism is in some fundamental ways counter-cultural, and fundamentally at odds with the political status quo.

But not disengaged. The current congress counts three Unitarian Universalists in the House. Two from California, Ami Bera and Judy Chu, and one from North Carolina, Deborah Ross. However, it’s unlikely there’ll be a UU president anytime soon. I think.

Questions of religion and spirituality are my great passion. You may have noticed. I’m especially interested in the modern divide of spiritual but not religious. With squishy terms like religion and spiritual let’s set up some definitions for this reflection. The word religion is a big subject. Starting mostly in the nineteenth century, the word has come to describe that part of a culture concerned with meaning and purpose. It has two principal expressions.

One is about defining and reinforcing the boundaries of a culture. A great deal of energy is put to the issue of who is in, and who is out. The second expression is usually more personal if not private. Spirituality is about, if you will, the deeper issues of meaning and purpose. Spiritual untangled from religion occurs as that social purpose of a religion begins to weakens, where a particular religion is less obviously about reinforcing a specific culture.

Today we’re in the midst of some terrible upheavals. While many countries can be defined by their majority religions, I think of Buddhist Sri Lanka and Hindu India as examples. Russian Orthodox shows a lot of cracks. And American Evangelical Christianity is capturing a larger part of the Christian identified, but Christianity itself is shrinking and rapidly. Over large swaths of the globe the close identification of a specific culture and a specific religion no longer can be assumed.

Boundaries are loosening. And people are responding sometimes out of fear and sometimes out of some larger vision. American Evangelical religion driving reactionary politics is a good example of fear-based responses. I suggest Unitarian Universalism is an example of responding from some larger vision. Of course, we’re not the only ones. But this reflection is about us.

What’s intriguing is that Unitarian Universalism as it both consolidated the older traditions of the American Unitarian Association and the Universalist Church of America, has been mutating over the past sixty-odd years in some very, very interesting ways. Ways that might mean we do not produce a president any time soon. But ways that might be of vastly more use for people on that individual quest, and socially and politically in the larger sense of helping people to understand who we are beyond the confines of our specific cultures.

The history is complex and trying to unravel it all is beyond the scope of a single sermon. But there is a bit of a paper trail. For many years our Seven Principles have proven a pretty good snapshot of what we commonly hold as important among us. It is interesting in a lot of ways, but not least of which is that while we can find our Jewish and specifically Christian origins in the supplementary documents, the principles themselves lay out something new. It is profoundly ethical, and it calls us to engagement in the world. While the spiritual of it is pretty private, and not spelled out very clearly.

And now we’re in the midst of a conversation at the denominational level about new language which might replace the principles. This language attempts to capture who we are and what we’re about now. I’m fascinated by how it is coming together. All the call to ethics and justice are there. In fact, they’re more explicitly spelled out. Especially regarding racial justice. But and I find this the most interesting thing, this call for justice is seen as the result of something. Our call to engaging the world as UUs is because of a radical intuition that the writers of the draft document call “love.”

It’s been a while coming. Our most successful public witness has involved yellow shirts and, first the slogan “Standing on the Side of Love,” and now “Siding with Love.” I’ve been to several major political demonstrations where non UUs refer to us collectively as the “Love people.” Among our most intriguing theologians Thandeka’s call to “Love Beyond Belief,” a reframing of the old Universalist slogan “Love over creed,” has had enormous resonances among us. I personally am intrigued by just how evocative that word “love” is, while at the same time being resistant to hard definitions.

It speaks to a grand intuition. And the part where the brain engages, where we look to consequences and definitions of this intuition, is how we manifest it all. Those calls to ethics and to the work of justice, specifically. But, perhaps for the first time since Transcendentalism, clearly and unambiguously calling us into some form of spirituality. Opening doors that we may not have even thought existed. Much less that were closed and should be opened.

The Unitarian Universalist songwriter Peter Mayer captures something about this in his hymn “Holy Now.”

When I was a boy, each week

On Sunday, we would go to church

And pay attention to the priest

He would read the holy word

And consecrate the holy bread

And everyone would kneel and bow

Today the only difference is

Everything is holy now

Everything, everything

Everything is holy now.

I should note that a dear friend of mine, a Christian Zen master, when she heard a clip of this song was offended. I’m not sure which part of her found the offense, the Zen or the Christian. Although I think it was within both.

The immediate issue can be that the first part of the song might be heard as a rebuke of silly literalists going to church and thinking that there’s a holy word and a holy bread. And, of course, a priest. An intermediary. The hymn could be heard as if all that were worthless.

To be fair, I bet a lot of people read or hear the lines exactly that way. Foolish them. But me, well, everything holy now. I offer that quickly, and as a caution. A caution because that’s actually not what the hymn calls us to.

Rather it is a call to the deep intuition. When we’ve turned away from the idea of our religion as a safeguard to some culture, specifically guarding our culture, telling us who is in and who is out. When we actually notice the feeling of love rising for and within this world, when we see that everything is holy now. Think of that word love. Think of the intuition of a profound connection among us, that web of interdependence. Well. What then?

When the rubber and the road meet. When our intimations of love, both as a private matter, and with social consequence, are not bound by our specific place, by our culture, or our country, what then?

I suspect that song speaks in part to the mystery. It in fact does not tell people to not go to church. It doesn’t say there is no holy book. It doesn’t tell us there is no holy bread. It doesn’t even disdain the work of priests, or shamans, or witches, holy witches. People who make the sacred their work.

It tells us of a small shift. One thing. A turning of the heart. A realization. An awakening. The new vision, really it’s as ancient as human hearts, but stated unequivocally: is that everything is holy. Larded through all of existence. It is a song of the good and the ill, in the heaven experiences, and in those hell realms. It sings of some holiness that unites everything.

Another wonderful word. Holy. Our English word holy comes from Old English and is related to a German word. It means blessed. Holy is also connected with whole. It hints at our seeing the connections. It is about what we experience when we find those connections beyond the parochial. It doesn’t deny the parochial, the intimate, but it does call us to something larger.

In practical terms it means Unitarian Universalist political engagement is informed by something that no one culture can claim as its own. There is nothing that can be excluded from it. In a final and in a terrible sense, what love tells us, is that there is no other to be excluded.

Love, lover, and beloved, are all facets of the divine. In love everything is holy.

It makes for messy politics. One obvious example. It challenges any idea of a border. It doesn’t say they don’t exist. It doesn’t say they shouldn’t exist. But it does say they’re permeable in ways that challenge all ideas of ultimate separation. And, more. It calls us into caring deeply and doing what we can for those on both sides of any border.

With that all things, intimate. As they are, you and me. The only difference. Well, a new perspective. A wild and open thing. Songs of intimacy. Songs of love.

So today UUs, well, we’re about something powerful and compelling. And, you know. In an era of fear, compounded by those who want to direct the fear at others, any others; all of a sudden our faith tradition throws our lot in with those others.

Doesn’t make us super electable. Not when a lot of money and attention are thrown at a candidate, say at the presidential level. Well. It might be a while before we see a UU president.

But. And. You know. The rubber and the road.

Religion today should, (should is such an interesting word, always invites a caution or two, doesn’t it?). Religion should, can, might, be about our personal quests, the healing of our hurt and longing. And. Religion now should, can, might, be about the great family, the web of relationships, the intimacy of all things.

Some love beyond belief.

Perhaps in this new age, this crossing of boundaries will be the politics of Unitarian Universalism.

I hope so.

Amen.