Zen, a New Universalism, and Politics

Since the nineteenth century, more or less the word “Religion” has come to describe that part of a culture concerned with meaning and purpose. It has two principal expressions.

One is about defining and reinforcing the boundaries of a culture. This has always been the principal purpose of religion as an artifact of society. A great deal of energy is put to the issue of who is in, and who is out. The ungenerous if often accurate characterization for this aspect of religion is “crowd control.” Sometimes it is. But like so many things in life as we look more closely, the more complicated it all is.

The second expression is usually more personal if not private. Here is where we find the unraveling out of religion something called “spirituality.” In this more contemporary usage, spirituality is about, if you will, the deeper issues of meaning and purpose. Spirituality is concerned with the most intimate parts of our lives.

This is mostly how I experience Zen. It is about the healing of the great wound in our individual hearts. It is the call to awakening. My awakening. Yours. It is about finding practices and guides. It is about throwing oneself, the particular, you or me, into the project, headlong, and full.

And there’s something else that is occurring in this fraught time. It’s part of that more complicated nature of things. Spiritual untangled from religion has only occurred because that primary social purpose of a religion has begun to weaken. And with that something else has happened that I find more than interesting. The weakening of religion as a social reinforcer has opened possibilities for religions. They have existed before, they’ve always been a part of religion beyond those other two points, but often lost in the power of those things.

The needs of so-called First World cultures to define themselves is shifting, and the specific place of religion becoming more marginal. I see forms of that here in North America in our civic religion. The trappings of patriotism, and the shadow nationalism continue unabated. But the place of specific religions representing the culture has fallen into that more complicated.

Today we’re in the midst of some terrible upheavals. While many countries can be defined by their majority religions, I think of Buddhist Sri Lanka and Hindu India as examples. But Russian Orthodoxy, despite the full-throated alliance between it and the Russian state, shows a lot of cracks. It is true American Evangelical Christianity is capturing a larger part of the Christian identified. And they are wrapped in the flag. But at the same time American Christianity itself is shrinking as part of the larger American demographic. Pew suggests it is genuinely possible for Christians to count for less than half the country by 2070. And even if they are the larger percentage, Evangelicals are in absolute terms declining. So far. It appears.

And not just here. Over large swaths of the globe the close identification of a specific culture and a specific religion no longer can be assumed. Boundaries are loosening. With this people are responding sometimes out of fear and sometimes out of some larger vision.

American Evangelical religion driving reactionary politics is a good example of fear-based responses. They are substantial, and sometimes frightening. They are about religion and its adherents trying to continue that place of cultural definition. All the emphasis on purity codes, aimed at women, and sexual minorities, and whoever can be named “other,” arises in this place.

But there is that larger vision which we can also see taking shape. I suggest we’re seeing a rising universalism among facets of the Christian community, especially within its so-called mainstream, including both Protestants and Anglicans. And. That’s where we’re finding this new larger vision informing a new and larger social concern. It is worth noting what that Universalism might be. Its origins within Christianity is as a rejection of hell.

And seeds of that Universalism are found in a number of twentieth century Christian thinkers. Protestants Karl Barth and Jürgen Moltmann are seen as presenting universalist leaning positions, Moltmann perhaps more unambiguously. The Catholic theologian Hans Urs von Balthasar is frequently accused of being a universalist, at least implicitly, or in a proto-universalist way. And the Orthodox theologian Segius Bulgakov appears to be pretty clearly a Universalist. To start a list.

I think it all hit the popular Christian imagination in 2011, when Evangelical Protestant preacher Rob Bell caused a stir with his book Love Wins. In the storm that followed he insisted he wasn’t exactly a Universalist. But apparently pretty much everyone else thinks he is. At the dawn of the twenty-first century the Reverend Carlton Pearson an African American mega church minister caused a national uproar when he unabashedly declared himself a universalist.

Finally in 2019, the major Orthodox theologian, sometimes described as one of the most significant living Christian theologians, David Bentley Hart has penned an eloquent personal confession of a Universalist faith, That All Shall be Saved. Professor Hart, known as something of a polemicist, argues that if some eternal hell were in fact a necessary component of Christian teaching, that would on the face of it, be proof Christianity is false.

What the percentages of contemporary American Christians are universalist is hard to know with any real certainty. Pew suggests that today some twenty-one percent of Christians explicitly reject belief in hell. I suspect the number is larger, but that’s based on informal conversations with clergy and my sense Christians are unwilling to admit they harbor a significantly divergent view. Still that twenty percent is in itself a number to consider. Especially in the light of so many prominent theologians and their shifts.

As to the owners of the trademark Universalist. While the Unitarian Universalist Association to the degree it can claim a singular theological current since its shift from being a liberal Christian church to a liberal church with Christians at the turn of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, has itself been involved in an internal dialogue turning on whether the word “Love” is the defining spiritual position of the Association.

Love and universalism have always been intertwined theological terms. In the Universalist Church of America, the slogan was “Love over creed.” It’s been a while coming. Unitarian Universalist’s most successful public witness since the turn into the twenty-first century has involved yellow shirts and, first the slogan “Standing on the Side of Love,” and now “Siding with Love.”

I’ve been to several major political demonstrations where non UUs refer to us collectively as the “Love people.” Among our most intriguing theologians Thandeka’s call to “Love Beyond Belief,” a reframing of the old Universalist slogan “Love over creed,” has had enormous resonances among us. I personally am intrigued by just how evocative that word “love” is, while at the same time being resistant to hard definitions.

What is particularly important here is that the UU form of Universalism is no longer about whether someone goes to hell. Instead, universalism is a view that all religions have truth about them. Not necessarily that they’re all the same, or go to the top of the same mountain; but that all religions offer authentic ways to heal the great hurt.

It speaks to a grand intuition. If there are ways in which we are all connected, if our deep longing and our stories of healing are each ways to help, then we begin to experience a deep sympathy across religions. We notice the universalist quality in that phrase “do unto others.” How all religions teach it. And it becomes a simple step to an ethic of care, attention to those who are being left behind, with that to works of justice.

And Zen Buddhism in the West is not unaffected by these conditions. Zen entered North American and Western consciousness first through artistic and literary circles. By the time it noticed the immigrant communities who had been there well before that handful of beat poets and academics took notice, Zen was firmly entrenched for the majority as a counter-cultural phenomenon.

There continues to be a strong cultural reinforcing component to immigrant Buddhist communities, including Japanese Zen and Chinese pan-Mahayana including Zen. But it is about preserving aspects, of cultural heritage, much more attenuated than the original culture itself. It becomes part of a sense of hyphenation, a thing, and an important thing. But also held more loosely. And among those communities not at significantly connected to Asian roots, the breakdown of that aspect of religion devoted to cultural definition, cohesion, and transmission is nearly complete.

Whether there will be a reformation with greater emphasis on the cultural aspects of religion in North American and Western Zen sanghas, is impossible to know with certainty. But, given the fragmentation of religious ties to cultural definition writ large, it seems unlikely. At least in significant percentage of those who identify as Zen practitioners.

What we see instead is a growing universalistic perspective. That larger one, which sees connections across boundaries, and some essential commonality. It is helped along by the subtle shifts out of the ongoing sometimes unconscious dialogue with the secular and scientific perspectives of the educated classes which continues to be the principal source of new Zen practitioners.

Instead of identifying completely with a nation, we are finding another and larger sense of identity. The themes of universalism are all about interdependence. When we’ve turned away from the idea of our religion as a safeguard to some culture, specifically guarding our culture, telling us who is in and who is out, then we begin to see something else.

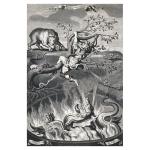

It tells us of a small shift. One thing. A turning of the heart. A realization. An awakening. The new vision. Really, it’s as ancient as human hearts, but stated unequivocally: is that everything is holy. Larded through all of existence. It is a song of the good and the ill, in the heaven experiences, and in those hell realms. It sings of some holiness that unites everything.

Another wonderful word. Holy. Our English word holy comes from Old English and is related to a German word. It means blessed. Holy is also connected with whole. It hints at our seeing the connections. It is about what we experience when we find those connections beyond the parochial. It doesn’t deny the parochial, the intimate, but it does call us to something larger.

In practical terms it means contemporary Zen Buddhist political engagement is largely informed by something that no one culture can claim as its own. There is nothing that can be excluded from it. To see the other in oneself is to find a form of love. In a final and in a terrible sense, what love tells us, is that there is no other to be excluded.

Not precisely one. Not exactly two. But rather a dynamic intimacy. Love, lover, and beloved, are all facets of the divine. In love everything is holy.

It makes for messy politics. One obvious example. It challenges any idea of a border. It doesn’t say they don’t exist. It doesn’t say they shouldn’t exist. But it does say they’re permeable in ways that challenge all ideas of ultimate separation. And, more. It calls us into caring deeply and doing what we can for those on both sides of any border.

With that all things, intimate. As they are, you and me. The only difference. Well, a new perspective. A wild and open thing. Songs of intimacy. Songs of love. In an era of fear, compounded by those who want to direct the fear at others, any others; all of a sudden our faith tradition throws our lot in with those others.

And it doesn’t have to be this way. There is a strong counter current within American Zen communities. People who feel the progressive spirit has gone too far. But at this point that is a minority report. From my view a necessary pushback against the excesses any trend brings with it. But a minority report.

What this observation does is raise some interesting questions. If it is true, Zen in the West will be joining the other religious communities who share this new universalist perspective. And., perhaps in this new age, this crossing of boundaries will be the politics of Zen Buddhism in the West.