Recalling the Western Zen Master

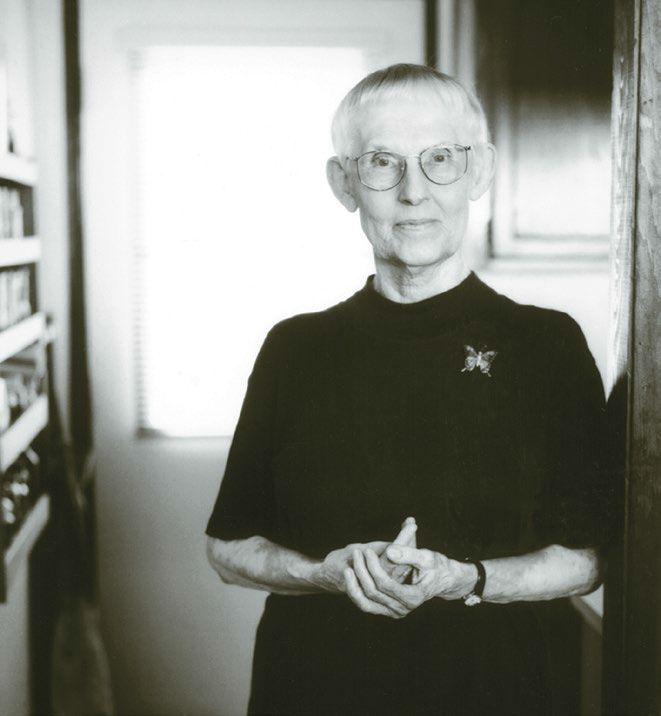

Charlotte Joko Beck

Charlotte Joko Beck was born on this day, March 27th, in New Jersey, in 1917.

Sadly, I can say little more about her early life. She attended Oberlin Conservatory of Music, and spent some years as a pianist and piano teacher. She married. They had four children. After separating from her husband Charlotte worked at various things, including as a teacher, a secretary, and an administrative assistant at a university.

She became an early student of the Japanese Soto Zen missionary Hakuyu Taizan Maezumi, also studying with the Sanbo Zen teacher Hakuun Yasutani & the Rinzai Roshi Soen Nakagawa.

I wrote about her in my history of Zen in North America, Zen Master Who? A Guide to the People and Stories of Zen. What follows is enriched from the base of that article.

In 1965, when she was in her forties, Charlotte Beck attended a lecture at the First Unitarian Church of San Diego. The speaker was the Japanese master Taizan Maezumi. She was struck by the quality of his presentation and quickly became a formal student. She attended numerous intensive meditation retreats as well as developing a solid regular practice. She also sat many retreats led by visiting teachers including as I mentioned above, the roshis Yasutani and Soen Nakagawa.

For a number of years she would drive from San Diego to Los Angeles, two hours each way, every Saturday for dokusan with Maezumi. Every month she drove up for sesshin, first with Gerry Shishin Wick, and later with enough others to create a caravan. These included future White Plum teachers Jan Chozen Bays, Susan Myoyu Andersen, and Anne Seisen Saunders.

Older than the majority of Maezumi Roshi’s students, she needed to keep a job to support her children and herself. As soon as she could afford to retire she moved up to LA and into the Zen Center. While resident at the Zen Center of Los Angeles she worked as Maezumi Roshi’s secretary.

She passed the Mu koan with master Soen. And then proceeded through the formal Harada-Yasutani curriculum. I am unclear as to when precisely she ordained but she received dharma transmission, acknowledgement of her own mastery of the Zen way by Maezumi Roshi in 1978. She was his third dharma successor.

After receiving dharma transmission she returned to San Diego and in 1983, with the assistance of Elizabeth Hamilton established the Zen Center of San Diego.

Following revelations of Maezumi’s sexual encounters with several students and other problems, in 1983 she broke with her teacher. Joko then founded the Ordinary Mind Zen School centered at the San Diego Zen Center. Sanghas founded by her students were located in New York City, Oakland, California, Champaign, Illinois, Portland, Oregon, and Brisbane, Australia.

By the 1980s Joko was generally recognized as one of the major Zen teachers in North America. Sociologist and Buddhist scholar James Coleman counted her among “the most influential women teachers in the West.” Buddhist scholar Judith Simmer-Brown singled her out in Joko Beck’s emphasizing “the practical quality of meditation practice, bringing Buddhism out of an abstract, conceptual realm into daily living.”

Ordinary Mind was among the first Zen communities to consciously engage the emotional life and the shadows of the human mind as the stuff of Zen practice. Joko ceased using titles and stopped wearing her priest’s robes. Liturgical forms in those centers affiliated with her, for the most part, became increasingly minimal.

Writing of her teaching, Shishin Wick noted how “Early on she realized that American Zen had to deal with emotional issues that Zen students could bypass on their cushions. Then when they left the zendo, these ignored issues emerged with a vengeance. Joko would say that without awareness our emotions would drag us around like a huge Great Dane, but once we were able to experience these ignored feelings without trying to avoid them, they might not go away, but they were more like a toy poodle yapping at us.”

Her style emphasized the ordinariness of Zen. One of her Dharma heirs Elihu Genmyo Smith once wrote of a dharma talk she gave. “’I am fully present about 15-20% of the time.’ This frankness thrilled many, as it went against the idealized (and nearly unattainable) image that Zen teachers were ‘always fully present.'” Among her heirs Dr Barry Magid noted, “To me Joko always stressed experiencing the absolute in the midst of the everyday. (S)taying with anger or anxiety wasn’t so much a technique for dealing with emotion as a way of seeing emotion itself, resistance itself, as IT. Not as obstacles on the path to be worked through and removed, but the path itself.”

Her teaching style was particularly interesting. While trained within a koan tradition she played down kensho, calling those experiences, large or small, “small intimations.” And of Dharma transmission itself she called it “no big deal.”

The scholar Matthew Ciolek’s “Sanbo Kyodan: Harada-Yasutani School of Zen and its Teachers” archive states Joko Beck named twelve successors. They are Ezra Bayda, Larry Jissan Christensen, Anna Christenson, Geoff Dawson, Elizabeth Hamilton, Greg Howard, Barry Magid, Gary Nafstad, Barbara Muso Penn, Diane Eshin Rizzetto, Elihu Genmyo Smith, and Peg Syverson. Several of her heirs have ceased teaching, a couple marked by scandals.

Several of her heirs have named their own successors. Barry Magid has five heirs, Pat Jikyo George, Marc Poirer, Claire Slemmer, Karen Terzano, and Andrew Tootell. Diane Rizzetto has named a single successor Dan Myoen Toshin Birnbaum. As has Elihu Genyo Smith, naming Ed Mushim Russel as an heir. Peg Syverson, who later also received dharma transmission in the San Francisco Zen lineage from Kosho McCall, has four successors, Todd Bankler, Joel Barna, Flint Sparks, and Laurie Winnette.

There were some controversies toward the end of her life, where she repudiated several of her heirs.

Her teachings were captured in three books, Everyday Zen: Love and Work (1989), Nothing Special: Living Zen (1993), and the posthumous Ordinary Wonder (2021). Everyday Zen is often counted among the more influential books from that first wave of North American Zen teachers.

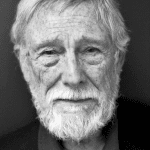

Her heirs are among the most interesting and in some cases among the most important of our contemporary Zen teachers. Among them, I think Barry Magid is the most illustrative of her unique approach to Zen. A psychoanalyst in addition to being a Zen teacher, Dr Magid’s numerous articles, and especially his books Ordinary Mind: Exploring the Common Ground of Zen and Psychoanalysis (2002), Ending the Pursuit of Happiness (2008), and Nothing Is Hidden: The Psychology of Zen Koan (2013) have continued to transmit the deep imprint of Joko Beck’s approach to the fundamental matters of our lives and deaths.

Charlotte Joko Beck died on June 15th, 2011 in Prescott, Arizona. She was 94.

Many bows for one of our singular Zen founders…