Back in April, Jan and I made our first visit to my seminary, the Pacific School of Religion since I graduated with my Master of Divinity degree in 1991. PSR nestles on Holy Hill above the UC Berkeley campus as a part of the Graduate Theological Union, itself composed of Catholic, Protestant, and Buddhist seminaries, as well as Jewish and Muslim centers. It is an amazing collaborative. I don’t believe there’s anything quite like it anywhere else.

And. It’s been thirty-two years. I didn’t even return to the campus the following year to be formally awarded my MA in the Philosophy of Religion. I’d been pulled into the whirlwind of parish life and didn’t have time. And circumstances since just haven’t led me back. So, this visit was a big deal. And not just because PSR had named me a distinguished alumnx, and that there was going to be a ceremony.

Among the many things that happened, some quite moving, two stand out as appropriate to share here today. First, was our visceral experience of what is happening within our North American religious scene. The second something I think directly important to us, here, today.

As you probably know American Christianity is shrinking as part of the larger American demographic. Pew suggests it is genuinely possible for professing Christians to count for less than half the country’s population by 2070. Evangelicals and Fundamentalists claim they’re growing. And that’s true. But actually, what’s hidden in the demographics, is that they’re capturing a larger percentage of that declining number.

Where these people are going is also important. There is some growth among other religions. But mostly the growth is among the disaffiliated. Almost one in three American adults are what we’ve come to call “nones.” As in none of the above.

Of course, for us within the Unitarian Universalist world, we occupy a strange and liminal space between the farthest edge of radical Christianity, cultural Protestantism, and secularity. We are, as they say, the barely organized religion. So, with no credal test, its why as a Zen Buddhist, I can be a UU. Or, as I think about our crowd, how we can come from pretty much any spiritual perspective, or, importantly, none. And have a place. Rather than having credal statements we are bound by covenants of presence. I’ll return to that.

Walking around the campus of the GTU what this steep decline for organized religions actually means was on full display. I knew that our UU seminary Starr King had left the GTU, principally because they could no longer afford the dues. They sold their building and are now housed in Oakland at Mills College. The old campus, which we walked by, has been joined with the also now defunct First Christian Church to form the heart of a small Muslim liberal arts college. Zaytuna College. The grounds are beautifully kept, and I absolutely wish them every good. But I also felt a wound from the loss. Starr King wasn’t my seminary, but it was an important school to me, and I took some critical classes there.

They’re not the only one. Another school I took a class at, the Franciscan seminary is completely gone, now consolidated into the University of San Diego.

In the years following the Second World War, some visionaries at my school PSR, started buying up real estate on Holy Hill. When Jan & I were there, they provided the larger part of student housing not only for PSR but for many of the students at the GTU.

One of the things I continue to love about the school was their married housing policy in the late 1980s. They were pretty conservative, in that if you wanted to cohabitate and live in their housing, you had to be married. But also, they were a fair bit ahead of some curves. If you could not legally be married, but wanted to, all you had to do was assert this and you could get the housing. Some heterosexual couples expressed annoyance that this meant they didn’t qualify, but gay and lesbian couples did. It tickled me at the time. A very long time ago.

Those buildings are all gone. PSR itself has shrunk to its core campus. And actually, it rents out some of that space. For instance, the chapel is rented by a preschool.

So, all that. Religion, certainly organized religions are in turmoil. Larger congregations are mostly doing okay. For now. While smaller congregations are mostly in deep trouble. It feels like those small congregations may well be those proverbial canaries in the coal mine. The whole idea of organized religions is being challenged.

That’s the second big thing. During the day at PSR, there were several presentations aimed at alumns. Jan’s and my favorite by far, was the panel presentation of the school’s junior faculty. Presiding over the panel was the dean Dr Susan Abraham, an Indian national wearing for the occasion a dramatic sari. She’s also professor of theology and post-colonial cultures. It felt like she was pushing along her brood of chicks as she introduced, occasionally teased, and constantly encouraged her, and it felt like “her,” brood. I had the distinct feeling no one dare hurt any of them with her around. Korean born Eunhye So teaches New Testament, Filipina American Lisa Asedillo teaches worship and ethics, and African American Leonard McMahon teaches spirituality and political theology.

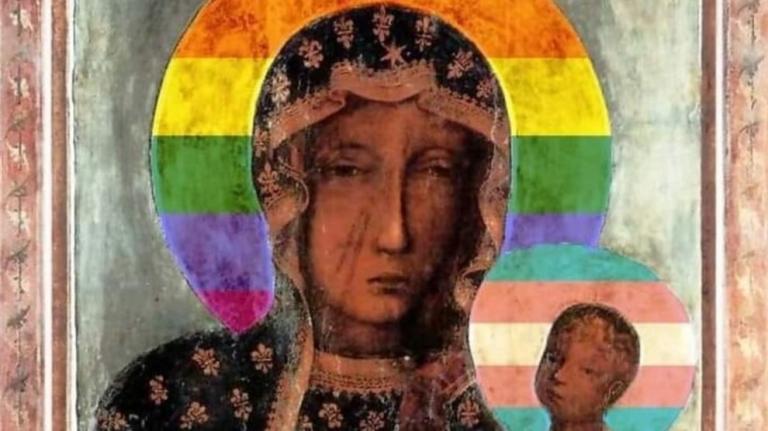

They are all so brilliant it hurt. PSR has always been about academic rigor. And. In my student days there, the ethos of the school felt to me basically like a nineteenth century Unitarian Christianity. If not precisely that, certainly relentlessly honest about text and tradition. This new faculty represents something even more daring. They all are committed to something they called a radically inclusive gospel. Not the Christianity of my childhood. And not the theology of the fundamentalist majority. The term they all embraced from different angles as the distillation of that radical and inclusive, they called Queer Theology.

As they made their presentation, a colleague whispered to her companion behind Jan and me, “I wish I could go to seminary now.” I thought, well, no. I don’t. But I got the enthusiasm. Really. I listened to these young professors and felt their brilliance and passion, and my body shivered. Something absolutely wonderful is happening. In the ruin of religions, as Christianity is seriously considering whether it is dying in the global north, as churches, temples, and synagogues are emptying, something quite wonderful is happening.

“Queer theology.” It sings into our hearts of great mysteries. I mentioned at the beginning how Unitarian Universalists exist within covenants of presence. Sometimes this is interpreted as being allowed to believe anything you want. You can. But the invitation is into the heart of presence, and what we can discover by being nakedly, unguardedly, passionately present.

Queer theology points to how this actively engaged presence can work. It arises from something called Queer theory. First, queer theory challenges heterosexuality as necessarily normative. It looks at the backside of the tapestry of the world we all assume. And shows how the threads come together to create who and what we think of as ourselves. Queer theology brings that challenge to religion and religious identity.

As a discipline it seems to have three aspects. First it means theology done by, with, and for the LGBTQIA community. Second, it challenges millennia old assumptions starting with boundaries defining gender and then noting the oppressions that have followed for those deemed outside those norms. And third, and maybe most importantly, it means theology opposed to any sense of a fixed position. Especially as regards sexuality and gender identity, but critically for all of us, as a liberating of human imagination from all our assumptions of what is.

It starts with an embrace of not knowing. Which I’m lucky to recognize from my Buddhist practice and study. But with Queer Theology that not knowing starts with our human bodies. And from there leads us into the brilliant and liberating darkness of endless curiosity. With this our human sexuality ceases to be a problem, and instead is the very place in which we find our deepest truths. In Western religious language, our bodies are where we find our salvation.

Heady stuff.

Now, please indulge me with one more statistic. With that we can unpack why I’m standing here more excited about the possibilities for spiritual growth and what that can mean in this world here and now, than I’ve been able to feel for a long while. This all speaks directly to who you all are in this gathering as the First Unitarian Church of Los Angeles.

So, that statistic. As of right now, according to the ACLU, there are 491anti-LGBTQ bills being pursued across the country. According to the Human Rights Campaign over 220 of these target transgender and nonbinary people. So far this year 45 laws have been passed including 13 banning gender affirming care for youth, 3 that require misgendering students, 2 that target drag performances, and 2 that censor school curriculum including books.

The best of times. The worst of times. Forward motion and backlash. How we can elect Barack Obama president and then immediately after through the vagaries of the electoral college system, end up with Donald Trump. These are dangerous, dangerous times. There are no guarantees. We can go in any number of ways. We can be opening the doors of perception and throwing open the gates to our liberation. Or, we can be living in a reprise of the Weimar Republic, a wildly creative moment soon to be crushed by totalitarian reaction.

Maybe a bit of both. Life is always dangerous. And we all will die. Something to remember. The question is how will we live within these tensions. In this place. At this time.

In our time and place there are three areas that we can find will open our hearts. They turn on our presence to and with the poor. As the good rabbi once said, “the poor will always be with us.” As we ask why, as we do not turn away, hearts open. Next in my list, is our presence to and with marginalized peoples. In our time and place the African American experience is most obvious. But that list is long. And it includes the minority that is a majority, women. Lots of marginalization. As we ask why, as we do not turn away, our hearts open.

And third are the queer. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, nonbinary, intersex, gender nonconforming, anyone, anyone who doesn’t fit our received idea of normative sexuality. In fact, women fit in here, as well. Because culture, certainly our culture puts male heterosexuality at the center, and makes everything else not quite right, if not fully wrong. As we ask why, as we do not turn away, our hearts open.

Each of these noticings is a gate. In fact we cannot afford to ignore any of them. Not if we’re seeking the great healing of our human hearts. If we want a religious community worth belonging to, I suggest it needs to be those three things. It needs to be a church of the poor. It needs to be a church of minorities. And it needs to be a queer church.

People have always had a boot on the necks of the poor. People are always using minorities as scapegoats for societal problems. And, well there are those near five hundred anti-LGBTQ bills winding their way through various legislatures. Right now. And speaking of right now, the reactionary wave of attacks on women’s rights that are going on right now are bone chilling and relentless.

Did I say dangerous times?

Which way are we going? As a people? As spiritual communities? As individuals?

We can’t control how things turn out. But we can choose how we will engage. What is true is the stakes are high. They’ve rarely been higher. And in the face of all that, a question. With whom do we stand? With whom do we throw in our lot? With whom will we live? And with whom will we die?

My hope for us today is that we be a church for the poor. My hope for today is that we be a church for women, for black, and for brown people.

My hope today is we become a Queer church.

This can open hearts. It can bring the edges into the center and show us new worlds of hope and possibility. It can show the world what love looks like. And it can show each of us what rests at the heart of our being. It can reveal mysterious truths about who we all really are.

So, how do we do that? How do we move from aspiration to action?

When I was in seminary at PSR all those years ago, my ethics professor was Karen Lebacqz. During a discussion in a class led by her, I stated I was a feminist. It was a moment when some women felt no man could be a feminist. Professor Lebacqz looked at me and looked at the class. Then she said, “James, you can be a feminist. All you have to do, is become a sister.”

Become a sister. Therein rests everything. The problem for our normative view is that being a woman is less than being a man. Being black. Being Asian. Being Latinx. Being poor. Who are we willing to stand with? And. And. More intimately, who are we willing to be?

Who can we be?

Each of us faces our own unique way in. If we belong to one of the traditionally marginalized if not outright oppressed groups, how do we include, deeply, profoundly include those others? And, of course, can we also include those identifiable as part of the majorities? Recall the project of seeing how the threads come together. And living from that deeper place.

This is an invitation into the sublime not knowing. Into deep curiosity.

What hope might arise for this poor, hurting world, if we surrender into the family of things? Into that deeper intimacy? What happens when we don’t know, but are endlessly curious?

Perhaps the churches and temples and synagogues we once knew are fading away. Time will tell.

But in the ruin of those institutions people are engaging the great questions. And out of that several pedagogies of the oppressed are emerging. Each with windows. Each with doors. Promising our liberation, our saving.

The most exciting of which, well may be Queer theology.

No guarantees. Of course. Still. Whispering to our hearts, the question.

Who will we be? You. And me.

Who will we be?

The great invitation.

Amen.

And, amen.

A sermon delivered

by James Ishmael Ford

at the First Unitarian Church of Los Angeles

June 4th, 2023