God.

A word that calls forth pain and joy. Hope and fear. And loss, so much loss.

People die for that word. People die because of that word.

God.

And, what is God? What is divine? And how does it relate to this world?

As it happens today marks the day in 381, that the Council of Constantinople promulgated the final draft of what we now call the Nicene Creed.

We believe in one God,

the Father, the Almighty,

maker of heaven and earth,

of all that is, seen and unseen.

We believe in one Lord, Jesus Christ,

the only Son of God,

eternally begotten of the Father,

God from God, Light from Light,

true God from true God,

begotten, not made,

of one Being with the Father.

Through him all things were made.

For us and for our salvation

he came down from heaven:

by the power of the Holy Spirit

he became incarnate from the Virgin Mary,

and was made man.

For our sake he was crucified under Pontius Pilate;

he suffered death and was buried.

On the third day he rose again

in accordance with the Scriptures;

he ascended into heaven

and is seated at the right hand of the Father.

He will come again in glory to judge the living and the dead,

and his kingdom will have no end.

We believe in the Holy Spirit, the Lord, the giver of life,

who proceeds from the Father and the Son.

With the Father and the Son he is worshiped and glorified.

He has spoken through the Prophets.

We believe in one holy catholic and apostolic Church.

We acknowledge one baptism for the forgiveness of sins.

We look for the resurrection of the dead,

and the life of the world to come. Amen.

At this point the wild varieties of early Christianity had long fallen into line behind the Pauline school. The school of Christianity that probably was closest to the actual teachings of the historic Jesus collapsed for all practical purposes with the sacking of Jerusalem in 70 AD, and with the death of its principal leadership. It’s hard to say whether the various schools we today clump together as “gnostic” ever were serious contenders. But certainly by the late fourth century they existed in no more than small communities at the edges of the empire or beyond.

The real question for at least two centuries was what variety of the Pauline schools would become normative.

The debates mainly turned on the nature of Jesus and Jesus’ relationship with God. An addendum was, and what is the comforter, the spirit that Jesus is said to have promised and which was associated with an event recorded as taking place shortly after Jesus’ ascension.

While Constantinople is called the “second” ecumenical council, and 56 years earlier at Nicaea in 325 the “first,” that is only what they are called today. There were a number councils before then. The first we have a sense of was the Council of Jerusalem somewhere in the middle of the first century. It’s attested to in the Acts of the Apostles. And between then and the “first” in Nicaea there are records of a dozen other councils. And also several after Nicaea that aren’t counted today. For instance, the Council of Antioch in 341, midway between Nicaea and Constantinople, in an attempt to reconcile what at the time were the Athanasian and Arian schools, offered a creed:

Following the evangelical and apostolic tradition, we believe in one God Father Almighty, artificer and maker and designer (προνοητήν) of the universe:

And in one Lord Jesus Christ his only-begotten Son, God, through whom (are) all things, who was begotten from the Father before the ages, God from God, whole from whole, sole from sole, perfect from perfect, King from King, Lord from Lord, living Wisdom, true Light, Way, Truth, unchanging and unaltering, exact image of the Godhead and the substance and will and power and glory of the Father, first-born of all creation, who was in the beginning with God, God the Word according to the text in the Gospel [quotation of Jn 1:1, 3, and Col 1:17] who at the end of the days came down from above and was born of a virgin, according to the Scriptures, and became man, mediator between God and men, the apostle of our faith, author of life, as the text runs [quotation of Jn 6:38], who suffered for us and rose again the third day and ascended into heaven and is seated on the right hand of the Father and is coming again with glory and power to judge the living and the dead:

And in the Holy Spirit, who is given to those who believe for comfort and sanctification and perfection, just as our Lord Jesus Christ commanded his disciples, saying [quotation of Matt 28:19], obviously (in the name) of the Father who is really Father and the Son who is really Son and the Holy Spirit who is really Holy Spirit, because the names are not given lightly or idly, but signify exactly the particular hypostasis and order and glory of each of those who are named, so that they are three in hypostasis but one in agreement.

Since we hold this belief, and have held it from the beginning to the end, before God and Christ we condemn every form of heretical unorthodoxy. And if anybody teaches contrary to the sound, right faith of the Scriptures, alleging that either time or occasion or age exists or did exist before the Son was begotten, let him be anathema. And if anyone alleges that the Son is a creature like one of the creatures or a product (γἐννημα) like one of the products, or something made (ποἰημα) like one of the things that are made, and not as the Holy Scriptures have handed down concerning the subjects which have been treated one after another, or if anyone teaches or preaches anything apart from what we have laid down, let him be anathema. For we believe and follow everything that has been delivered from the Holy Scriptures and by the prophets and apostles truly and reverently.

It failed to catch hearts. Or, at least critical leaders. And so, the march toward an orthodox view proceeded to, well, that day in 381.

One could say it’s all very philosophical. Certainly it tumbles quickly into the abstract. The arguments really turning over how God like was Jesus? Is there one God and Jesus is somehow very, very special? Or is that so special he was the first thing the one God created? Or is he in some way identical with God?

When we look at Paul’s letters we can see each of these views, if we want.

So, which one?

There was little tolerance for diversity of views. One definition needed to become the yardstick of orthodoxy. Looking for why this would be so one need look no further than the fact the church was now tied up with the state. And emperors don’t like wiggle room. One God, one religion, one ruler.

Within the empire there would continue to be doctrinal controversy for a while yet. The so-called Nestorian school would split off over the question of whether Jesus himself had two natures divine and human, and later the so-called Monophysites over whether Jesus had a single and divine nature. The former represented in the Church of the East, and the later as the Oriental Orthodox. However, both were essentially Pauline. And both professed the Nicene Creed.

The only significant non-Nicene church, the Arian churches would survive the condemnations of the Creed of 1st Constantinople and final draft of Nicaea for some time. The Gothic churches were adamantly Arian and had full alternative hierarchies and churches. And with the collapsing western empire the Arian churches thrived. For a time. The records suggest they were vastly more tolerant than the Athanasian now called Nicene Christians. It appears it was certainly better to be Jewish under their rule than under what we now call the Orthodox.

Whatever else may be said, Arian churches lasted until the seventh century, the last known Arian kings were Grimoald of the Lombards and his successor, Garibald, who died in 671.

So, while not the end of the story, today, 1,642 years ago today is more than significant in the history of the Christian churches. It might even be called the real birthday of the Christian church we know. An argument can be made.

However, what it is for sure, is the time when the orthodox Christian doctrine of the Trinity was set.

So ends the history lesson.

Then there’s the artifact of the Trinity itself. And its attempt to describe a great mystery. What is divine, and how does it relate to this world?

Truthfully this sort of thing resists language.

In fact defining the mysteries of the divine appears to be close to impossible. Maybe its actually impossible to unpack the Trinity without falling into one heresy or another. I rather love that, and I have to admit enjoy the struggles of my more orthodox colleagues wrestling with the subject on Trinity Sunday.

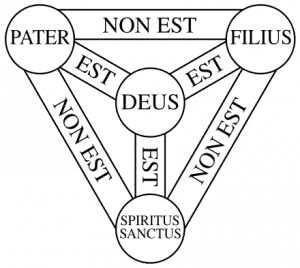

Me, I find this mystery of the meeting of the divine and the world is often best found in song, or dance, or images. And so, with the Trinity, there’s the Scutum Fidei.

No one knows the precise origin of the image, but probably it emerges from about the twelfth century. The earliest certain version is found in an early thirteenth century manuscript of Peter of Poiters’ “Compendium Historiae in Genealoga Christi.”

It’s basically a triangle with the three points usually enclosed in circles reading Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. In the middle was another circle labeled God. Each of the connections in the various directions were labeled either “Is” or “Is not.” And with that, a description of the mystery of the Christian image.

My spirituality is deeply rooted in the Zen traditions. And I’m a long time Unitarian minister, the very name is rooted in a conscious rejection of the Trinity. However, in my own spiritual life as a practicing Zen Buddhist, I cannot say quite where I realized the purest formulation of Zen’s fundamental teaching that form is emptiness and emptiness is form, as precious and important as it is, misses something of our human encounter.

It was only when I felt into the Buddhist trinity, or, at least one of the Buddhist trinities, the mystery of the Trikaya that I found my path opening fully.

Here we have the two assertions of reality. The truth that nothing has a substance, that everything is wildly and completely open: Dharmakaya. The truth that everything plays out in causal relationships, constantly creating and falling apart, the realm of action and of history and of consequence: Nirmankaya. The mystery includes the absolute identity of these two, for the lack of a word, things. But, there is a third thing. That third. The truth of ecstasy, wonder, magic, and dream: Sambhogakaya.

Now, I feel no need to cram the two trinities, Christian and Buddhist into each other. Although they sort of do. As my friend the Zen student Dana Lundquist observed out of her own walking the spiritual path, “There are a lot of different true things happening at the same time.”

For me one can say with absolute truth there is no God. And, yet. Like Issa’s poem, the morning dew is the morning dew. And yet. This world and our hearts are filled with that spirit of an and yet. God, gods, the sacred are in my experience, absolutely a part of the world in which I live.

The languages of divinity sing of realities I experience.

With that, there’s another image for the Christian trinity that I find wandering in and out of my dreams. Pointing. Inviting.

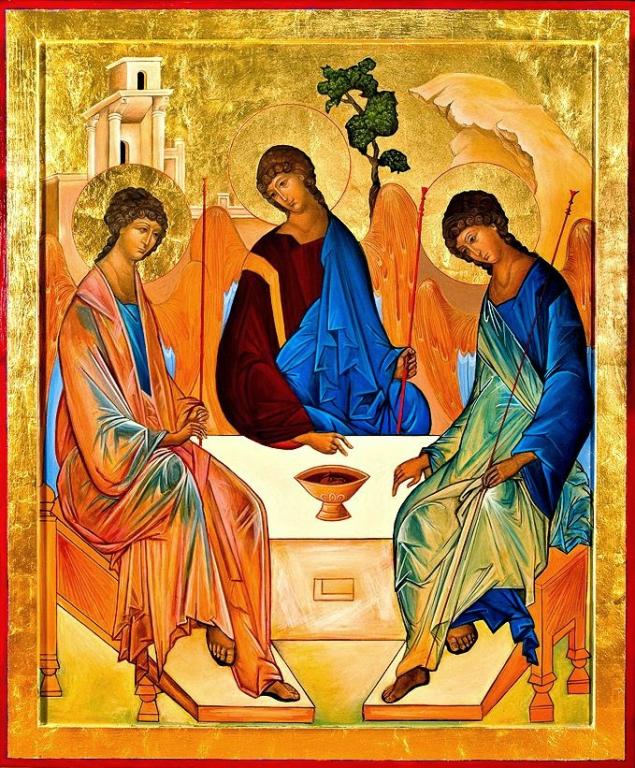

The image of the Christian trinity that has most touched my heart was an Orthodox icon created by a fourteenth century Russian artist, Andrrei Rublev. He used a story from Genesis of Abraham being visited by three angels and with that as his material creates a trinity image I find haunts my dreams. It includes languid humans sitting around a table. There are within it unseen triangles and circles that cannot be contained within the painting. Beyond that the play of images and colors that we can encounter simply seep into the preconscious heart and envisions, again, something that the mere painting cannot hold. Mere words. Mere actions. But without disdaining those mere things.

I really like that.

I, well, I really believe that. Shinjin. Trusting heart. The way I’ve come to understand those other words of my spiritual life, awakening, enlightenment. It’s where heaven and earth meet as my heart.

Mystery piled upon mystery.

We don’t know it. We can’t grasp it. We can only open to that mystery. Sing it. Dance it. Paint it.

And maybe even sing the odd Hallelujah.