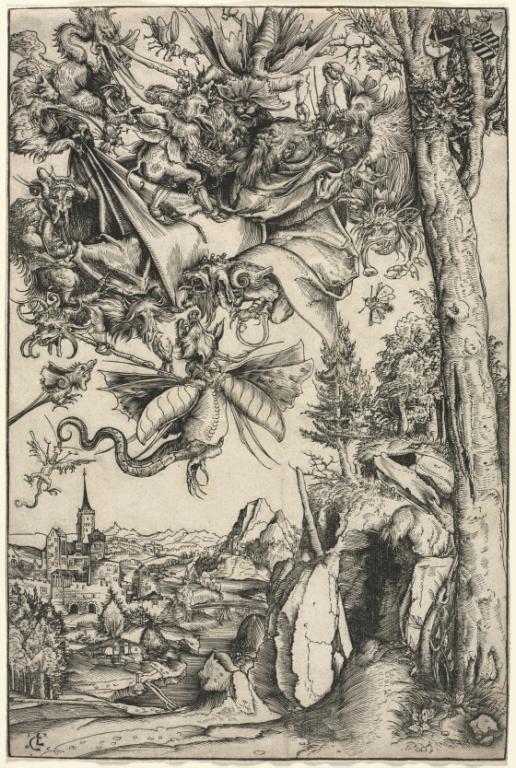

Lucas Cranach

16th Century

I have seen the freest and best educated… in the happiest circumstances the world can afford; yet it seemed that a cloud hung on their brow and they appeared serious and almost sad even in their pleasures (because they) never stop thinking of the good things they have not got.

Alexis de Tocqueville[1]

Among the various smaller and larger tragedies of Zen’s taking root here in North America was what happened when Daido Loori, one of our more charismatic native born Zen masters died. He had established a major training temple, and when he died, one of his senior successors, Konrad Ryushin Marchaj was named abbot. The new abbot had trained for many years and was seen as a clear-eyed teacher.

After a few years it all collapsed. While married he had conducted an affair with someone outside of his community. Itself damaging to many people. But there was something else going at the same time. He had become interested in the South American hallucinogen, Ayahuasca. It appears he gave dharma talks while intoxicated. He was asked to step down as abbot because of the affair, but it seems obvious his drug use was in the mix, as well.

Which when I first heard it, I thought, well, I’ve known of others who’ve given dharma talks while drunk. Taizan Maezumi, a Japanese Zen teacher central to the establishment of Zen in the West and Chogyam Trungpa, a very prominent Tibetan master popped up in my mind pretty much immediately.

I’m not by any means making excuses here. These are damaging acts, and not to be excused with euphemisms such as “crazy wisdom.” Accepting the role of spiritual director comes with more stringent restraints on behavior than might otherwise be the case. The cure of souls, as it was called in the west, is a powerful thing. And boundaries and consequences are important.

Coming at this from another angle I recall how someone who had been interviewing Buddhist teachers for several years noted he’d never met a “full Buddha.” When asked what should a “full Buddha” would look like? How would you know? The response was that there’d be no self.

Here I think we find a part of the problem and something worth pausing to consider.

There are spiritual traditions that assert there is no self, that what we call ourselves is a delusion, a dream, or an hallucination. Now there are truths within such an assertion. But, the principal point, certainly, the point we find in Zen is that of course there’s a self. To ignore that fact on the ground is a profound mistake.

A major point is that our selves have no abiding quality. Our sense of self is the product of causes and conditions, genetics and history, all coming together in a moment. We call that moment our self. It can hang together for a while. That moment runs from birth to death. Although truthfully it is changing all the time between birth and death. But there is some big part of it, a sense of continuity, a thread of memory. However, however true or illusory, it ends with the disruption of the elements that have come together to form a self-aware entity.

Buddhist metaphysics can obscure this point. And it is doubly complicated by the fact of variations among the schools. While Tibetan Buddhism seems to teach a form of reincarnation, at least among their deepest realized practitioners, most other schools speak of rebirth. The distinction is that in reincarnation one can posit something that moves from body to body, while in rebirth what passes from body to body are simply bundles of karmic consequences. More like one’s children than one’s self.

The critical point however is impermanence. We’re real. We’re also impermanent. Much of our human suffering is our emotional and psychic response to that impermanence. It is the first noble truth of Buddhism.

There’s also a corollary to this. It is the secret teaching of the Mahayana, the great way. What we’re going to experience in our spiritual lives is no different than what we’re going to experience in our physical lives. The sadness and joys of our existence continue before and after awakening.

That impermanence, that lack, that emptiness. It isn’t just that everything dies. It is that everything is dying in every moment. And even more, that every moment is in itself empty, vacant, if you will, dead. Life and death are bound up together as something that can be called one, or at the very least, as not two.

So, with that, our shortcomings, our failures, our personalities, they are the stuff of our awakening. This body in all its complexity, this mind in all its wonder, is the place where the magic happens. There is something kind of wonderful in this. But it is easy to miss, and once we notice it, it is easy to forget. This is part of the spiritual conundrum.

And it is a problem with the stories we tell ourselves about awakening and salvation. Most stories in most spiritual traditions say it’s one and done. Mainly because that’s true. To see deeply into the matter, to touch the heart of the matter, to have that experience of healing and salvation, happens. But it happens within and as who we are. And that remains. Our bodies and our minds abide, for as long as causes and conditions allow. And during that time we find ourselves playing peek a boo with our true nature. Now we understand, now we don’t.

For those of us who have trained in the koan system associated with the great eighteenth century Japanese master Hakuin Ekaku, there is a choke point in our training. After we meet this emptiness, and our sense of this as our own intimate truth we’re asked a question. What is the source of this emptiness? In some schools the question is organic, what is the root of this emptiness?

We must touch this source, and we must touch this source with all our heart and mind and body. An interesting consequence to touching this place is that many people experience a let down. I had what I’d have to call a moment of depression. A sense of lack in all that might mean negatively.

We are touching our ordinariness. It isn’t This Very Body with capital letters, it is this very body. Yours. Mine. This one. Not some other. And it comes with all the same issues that were there when we began the journey. In western traditions this is noticed, and a common prayer is to remain constant to the end. The prayer because we know it doesn’t have to end that way.

As the Zen poet Ryokan noted, “Last year, a foolish monk. This year, no change.”

I’m concerned with what happens after we’ve had a glimpse of our true nature. What about now? How is it different than before?

Well, there isn’t a lot of difference. If our insight is deep, like being struck in the heart with an arrow, we’re graced with some quality, where no matter what happens, we never totally forget. Although we can forget for long enough to do ourselves and others real damage. If our insight was more like being grazed by the arrow, we can just plain forget.

We are wise to assume our insights are never steady state. And we should always, always be cautious about what we think is so.

Here I find it wise to think of that term crazy wisdom. The term comes from the Tibetan tradition. And it speaks to people whose realization manifests in ways contrary to our cultural norms. It’s a good term. We can see it manifesting in different religious traditions. In Sufism there are madzubs, a person who is “divinely intoxicated.” We see examples of holy fools throughout the history religions, and their mystics.

As for the former abbot. He professed a need to continue to investigate the matter of his mind and he found psychedelics seemed to help. They might. I have no hard view on the subject. But it was critical he resign his abbacy. That is a specialized task, and it had clear boundaries.

For the most part such ecstatics have excused themselves or have been excused by divine grace from meeting the world and its conventional expectations. It is a special calling. And these people are only sometimes actual spiritual directors. It can be too confusing. So long as they keep within the bounds of their vows, it is fine to bow to their eccentricities. But not beyond them. When a teacher seems to be acting in a self-serving way, for the most part, it’s wise to assume they are.

The same thing is true for us as practitioners of the intimate way, as pilgrims of the heart. And with that the question is how do we see our own thoughts and actions? What do we believe we’re doing when we don’t govern ourselves and what we do?

Like with medicine, the first vow of a serious spiritual practitioner is to do no harm. More deeply how do we meet ourselves and the world as full Buddhas? Buddhas with desires and resentments and hatreds and endless foolish ideas that we’re sure are as true as truth itself. While each of these things are in fact gates into the mystery, by indulging them they become barriers.

The arts of the spiritual life are how to encounter the gates. In this case, how do we meet the obstacles of being ordinary people? Confronted with the intimate truth that this moment and this place is the buddhaland, is heaven, how do we act?

I think of Dr Marchaj. I can envision a time when he incorporates his new explorations as a teacher in a new context. The world isn’t done revealing itself and we are particularly in a time that invites profound and wholehearted explorations beyond the boundaries of conventional religions. Time will tell.

But there’s something else in all this, something important.

Here I find myself returning to that observation made by de Tocqueville. He was observing early American culture. And I believe a trait we continue to have. At the time he was comparing Americans to poor people he was aware of who seemed more satisfied with their lives. This is a common observation of people who come from poorer cultures to more affluent ones. And similar to people who notice how little they may have had in their childhoods, but never thought of themselves as poor.

While those who have studied the matter observe, money is important to happiness. In money cultures, at least. There is a saturation point, beyond which more money doesn’t make things better. That point is a bit of a moving target, and beyond the point here. Which is, after attending to what needs attending, how do we meet the world?

After we’ve touched the intimate matter, after we’ve seen into the deep possibilities of our lived lives, how do we meet our lives? Knowing these things of our lives can be gates or boundaries, how do we live? Specifically knowing we are built dissatisfied, that our bodies want, how do we deal with it?

We are born dissatisfied. How do we meet our inherent need for novelty?

Henry Thoreau, another of those people who walked deeply into the mystery, but who was a bit more of a madzub than personal guide called us all to “simplify, simplify, simplify.” He said to let one’s affairs fall to two or three things. Probably not possible for most of us. But pruning, and letting go, are wise words.

I’m much taken with how the organizing consultant Marie Kondo who originally counseled people to cut back on anything that one didn’t need, or as she liked to say, give one joy, found her life complicated with children. Some people expressed disdain for her turn to a bit of a mess. But me, I saw something of a pointer.

We need to learn to meet the moment. Sometimes its tidying. Sometimes its living with a small tornado racing through your life. Observe, watch, witness. Return to the pillow. Notice. Judge as little as you can. And act when you must.

Remember the desire for novelty is as natural as natural can be. And at some point it is harmful to the spiritual life.

Enjoy that cup of coffee or tea. Fully.

And when the cup is empty, put it down.

Notice. Be aware. Meet the mystery. Even when it is boring. Especially when it is boring.

Traps and possibilities await. What matters is how we meet the moment.

[1] Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America, Anchor Books, 1969, p. 536