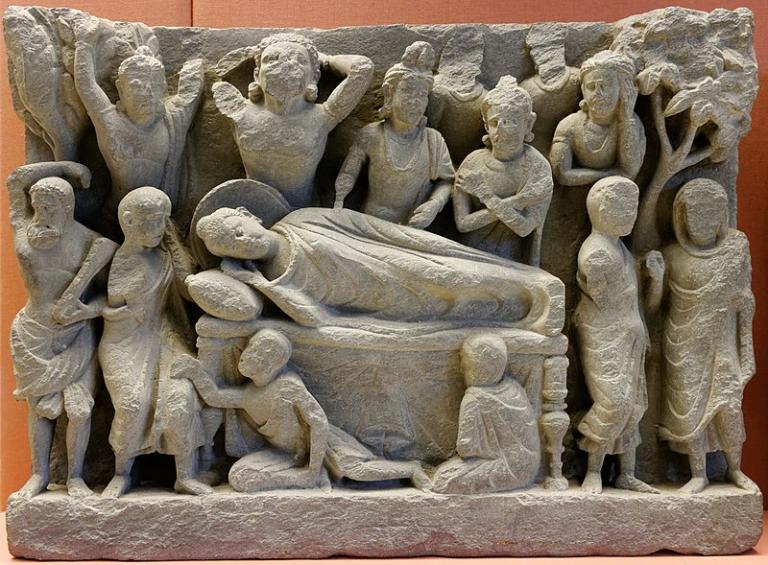

(Gandhara schist, 2nd-3rd century)

We seem to be endlessly fascinated by people’s last words. They are often taken as summations of people’s lives. And perhaps that’s so. At least on occasion.

Pretty much everyone knows of Oscar Wilde’s last words said in a cheap hotel room. “My wallpaper and I are fighting a duel to the death. One or the other of us must go.” A pretty good example, I find, of how our words do take on the cast of summation. Again, at least on occasion.

For an example of wise words rather than witty, the wondrous Isaac Newton is said to have said, “I don’t know what I may seem to the world. But as to myself I seem to have been only liek a boy playing on the seashore and diverting myself now and then in finding a smoother pebble or a prettier shell than the ordinary, whilst the great ocean of truth lay all undiscovered before me.”

Others were more immediate in their concerns, and capture a fundamental appreciation. Like Arthur Conan Doyle who said to his wife “You are wonderful.” And Jean-Paul Sartre, who said to his wife Simone de Beauvoir, “I love you very much…” Or, Steve Job’s famously reported, “Oh wow. Oh wow. Oh wow.”

All that noted and with Karl Marx’s alleged last words, “Last words are for fools who haven’t said enough” as a caution, I find myself fascinated with the question, what were the last words of the Buddha?

According to tradition Gautama Siddhartha, the Buddha of history, was eighty years old when he died. His long life was dedicated to a great search, a finding, and then forty years of teaching. The stories say as he fell with his final illness at Kusinagara he lay on a bed made for him between two Sala trees, his head facing north, his face turned to the west. Of course, of course, flowers endlessly bloomed on the tree, falling and replacing. At dying, like with birthing, miracles abound.

And. Of course, being who he was, shortly before he died he delivered a final sermon.

We have two principal versions that concludes the sermon.

The Mahayana version in it’s earliest strata may date from the first century of the common era. Already some four or five hundred years after Gautama Siddhartha died. And to make it more complex, the texts we have don’t come into full shape until the fifth century. What we have is essentially a Chinese text. And, is critical for its development of the teachings of our original Buddha nature. A classic of the Mahayana, considered by some to equal the Lotus Sutra in importance. And, for those of us interested in last words, it actually concludes with him laying down. There is no reference to anything said in the immediate as he faced death with each breath possibly the last.

The Theravada version is no doubt closer to the actual Buddha, at least chronologically. At least sort of. Maybe it can even be dated from as near as a generation or two from the time of the Buddha. Although, and I believe this is critical, it was not written down until much later, somewhere near the beginning of the common era. Back to that four or five hundred years.

Everything we get about the historic Buddha has to be understood through that limitation, nothing was written down until hundreds of years after he died.

That noted, this is something that probably was critical to many people even at the beginning. When faced with the last breath, what did the master say? I suspect, I feel, I’m even confident that what we have is probably pretty close to what the dying monk actually shared with his disciples.

And it has what we have:

And the Blessed One addressed the bhikkhus, saying: “Behold now, bhikkhus, I exhort you: All compounded things are subject to vanish. Strive with earnestness!”

In another translation:

“Behold, O monks, this is my last advice to you. All component things in the world are changeable. They are not lasting. Work hard to gain your own salvation.”

One could spend a lifetime unpacking these particular last words. And people have. For me the most successful of these unpackings, is found in the “four seals.”

The formulation of the four seals don’t seem to date much earlier than the “The Questions of the Nāga King Sāgara,” the Sāgaranāgarājaparipṛcchā, which itself doesn’t seem to date earlier than the third century before our common era, and is likely much later.

Of course, it is simply an explicit ordering of what had been taught for hundreds of years as the heart of the Buddha’s teaching. The four seals, I believe unpack those last words of Gautama Siddhartha.

The first three are:

1) Impermanence: Everything is made of parts, and they will inevitably come apart. This speaks to the fundamental structures of the universe as well as to the creation of our minds. But it is the mind, it is the heart that it’s most critical for us to understand. We are real. But we are impermanent.

2) No-self or the Emptiness of Self: There is no abiding self. The self is real. As I said, we are real, you and I. Pinch us and we hurt. But our existence is mutable. And in the end, we are mortal. Nothing escapes the dissolution of the body. The wonderful mystery that we are, our unique noticing of the universe, our little corner ends.

3) Dis-ease or Disquiet: The motion of things rising and falling is experienced by humans as painful, causing anxiety and anguish. I call this encounter the buzz. The buzz is in the back of everything we encounter, behind every victory.

These first three are found in some lists as the “marks of existence.” But I find they lack something. And that something is expressed as the fourth seal.

4) There is a way through the hurt. This is the good news of Zen Buddhism. While the buzz belongs to the universe, it’s the experience of everything in motion, the buzz as discomfort, dis-ease, anxiety, or anguish belongs specifically to our human world. Given the size of the cosmos, “human” here would be any being with a consciousness that can discern the first three seals.

There is a way through. Call it enlightenment. Call it awakening. Call it peace.

The Buddha’s last words, unpacked.