A student of the intimate said to the master Yunmen, “The radiance serenely illumines the whole universe…” Before he finished Yunmen asked, “Aren’t those Zhangzhuo’s words?” The student said, “Yes.” Yunmen said, “You have misspoken.”

Gateless Gate, case 39

I never graduated from High School. At 38, when I finished my undergraduate degree at a commuter college, I had a thought of attending the commencement ceremony, but it was inconvenient, my eyes were on graduate school, and finally I didn’t. Then just before my 43rd birthday, I walked the boards at the Pacific School of Religion, as I received my Master of Divinity degree.

My wife, mother, and auntie all came. They were dressed in their best. As I was on my way into ministry, it was advised I own my own Geneva gown to wear as well as to purchase the master’s academic hood. The hood would be formally presented during the ceremony. The commencement was outdoors, and it was a hot day. I recall sweating. I recall holding the announcement for the program and seeing my name printed on the card stock.

Finally, there was the procession, then hearing my name called out, stepping forward, being presented with my diploma, having the hood placed over my shoulders, and receiving many, many handshakes, and later hugs, among us tears.

As I stood on that lawn with my family and all those other graduating students and their families and closer friends, I realized that at that moment how nothing special really happened. It was just people doing some things people have done for generations. Some of it pretty silly. That academic hood created following procedures first laid down in the Middle Ages had absolutely no practical value. It was still hot. And yet, and yet the world had shifted. For me, for my family, the world had changed.

And it felt right to honor the moment with these forms and actions and even special clothing. I realized this showed much of the heart of rituals, of liturgy. Liturgy comes to English from French although it ultimately derives from Greek. It means public work, or the work of the people. Ritual enters into English in the late 16th century by way of Latin, meaning sacred observance, customs, and usage. It’s connected to the word rite, also from the Latin, meaning the act or procedure performed according to a customary pattern.

Humans do rituals. It’s part of our being the symbol making animal. Fourth of July parades, graduation ceremonies, baptisms and dedications, recognizing a child’s coming of age, weddings, funerals are all rituals. Some are religious in nature, others are not.

We’re all familiar with the term “rites of passage,” a term coined by the French ethnographer Arnold Van Gennep in 1960. The rituals of rite of passage can be critical to our well-being, to finding ourselves within our lives.

Over the many years I’ve accompanied many families suffering a death among them. What I observed was that those who had a ritual moment acknowledging the loss weathered the time following better than those who did not. Not a hard rule, but a pretty good rule of thumb.

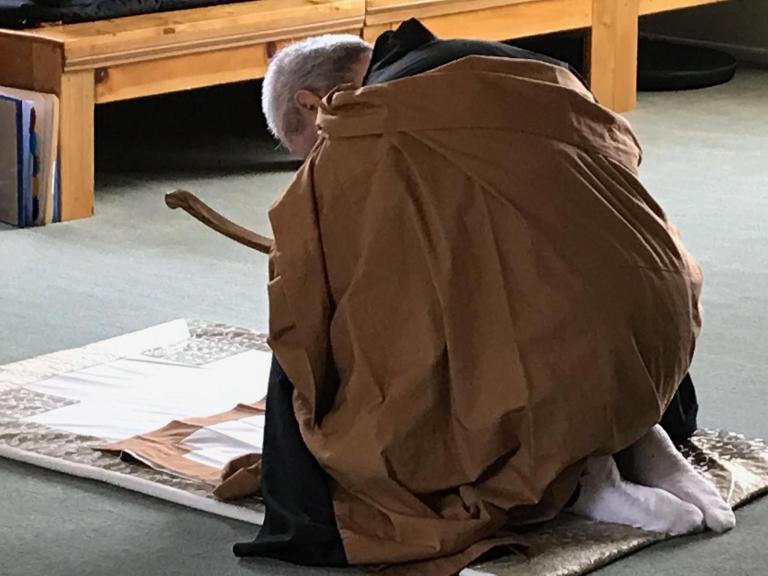

Rituals are part of all religions. A classical definition of ritual in religion suggests four elements. It is a repeated action. The mass or that offering of incense in a Zen temple, for instance. It is set out of regular time. That is, it is separate from our ordinary actions in some manner. It follows a pattern. And it carries the story, the myth of the tradition in some way.

For instance in the Gateless Gate, case six.

Once upon a time the world honored one was at Vulture Peak. Before a vast crowd of lay practitioners, nuns, and monks, angelic creatures, and even gods, he held up a single flower and twirled it. Of the assembled crowd only the disciple Mahakashyapa, responded, breaking into a wide grin.”

Commenting on this most famous of Zen’s sermons and that little act of twirling a flower and smiling, Carl Jung once suggested this is not far from the Mystery of Eleusis where the priest held up a reaped ear of corn. And not unlike the transformed wine and bread presented by the priest at the Christian communion. Or the offering of a stick of incense at a Zen morning liturgy.

Liturgy means “public service,” or “the work of the people.” Within a Zen context the late John Daido Loori Roshi was fond of saying, “Liturgy makes visible the invisible.” Making the invisible visible in Zen means bringing our whole lives together. Liturgy is a symbolic expression of that fullness, which, like zazen, opens us to a way of being in the world. So, even if we in the West are no longer supported through that work of creating and transferring merit, liturgy remains important.

Here we find the power of non-separation, the reality of our intimacy with the ten thousand things. Rituals reveal the fundamental truth of our lived mutuality, embodied. Or, can. Engaged with full hearts. And bodies.

Such engagement captures the whole world. All of it. Our lives and our stories collapsed in a moment of noticing. Just this. And from this noticing. From that flower as it twirled. From that smile, that lovely grin. Just as it happened. With an offering of incense and a bow.

Rituals place us in the rounds of life, give us a sense of rightness including healing hurts, they draw our attention into our sensory experiences, and can inspire us as we live through the vicissitudes of life. On that hot June day in Berkeley, California, I got it.

Liturgy and ritual are an important component of communal self-definition. Which is both important and dangerous. Especially as while it reinforces who is “in,” it also enforces who is “out.” It is a powerful, and therefore, dangerous part of all religions. And if used carefully, it is potentially one of the most powerful of spiritual practices.

We humans all have our little and big rituals which can simply be brushing our teeth in the morning or making a cup of coffee exactly the way we want it. And sometimes it can be unhealthy. In that big way of cutting other people out, or in a more intimate way in an obsessive action. The compulsive acts that are part of the diagnosis of obsessive-compulsive disorder. As Paul famously notes in his second letter to the Corinthians “the letter kills, but the spirit gives life.”

There is doing the ritual, getting lost in it, missing the whole point. There’s Yunmen’s point when telling the student of the intimate that merely quoting a poem describing facing into the real is a mistake. What he invites is not ignoring the poem. He is inviting the practitioner to find the real and making the writing and reciting of that poem the student’s own.

Rituals small and large, private and communal, are part of how we human beings interact, communicate, both within our inner lives and as members of a society. The Zen tradition has evolved a number of rituals to help along the way. There are daily rituals such as those surrounding meditation, having a particular place, lighting candles, offering incense, concluding with a verse. There are weekly rituals, for many joining with others for meditation once a week is an example. There are seasonal observations. For many attending retreats at least quarterly. And there are annual observations. The great festivals of Zen such as Rohatsu, marking the enlightenment of the Buddha as our own.

There are ritual acts like eating meals in a formal way, oryoki in the Japanese tradition and barugongyang in Korean. These are powerful disciplines. Actually there are ritual ways of engaging all the daily activities of life.

A connecting thread for rituals of daily life can be the recitation of gathas. The word means to speak or sing. In Zen gathas are brief phrases, perhaps just a word, maybe a verse recited at various moments in the rhythms of our lives. Traditional gathas in the Zen world include a verse recited before putting on the rakusu, a small vestment worn by many Zen practitioners, the three refuges, and the four vows.

But we can have our own gathas, and many people do. A grace at mealtime. Something for when we get up in the morning. Something before we go to bed. Perhaps something for when we are about to use a restroom. Someone suggested to me it might be good to have a gatha before turning on a television set.

Several Zen teachers have shared versions of gathas including Robert Aitken and Thich Nhat Hanh. You can profitably use theirs. You can compose your own. For instance.

As I awake, I offer myself into the great project of noticing, of being present.

As I wash the dishes, I offer my attention to the disciplines of life.

As I experience anger, I offer a moment to untangle, to notice the heat.

As I notice birds calling, I offer up my ears.

As I listen to the news, I offer space.

As I settle into bed, I offer a moment to feel the quiet.

Collect ancient verses, find collections like Aitken Roshi’s volume Zen Vows for Daily Life. Discover the rhythms of life and death in these moments.

The radiance serenely illumines the whole universe…

These moments touch the real. They channel the real. They are the real.