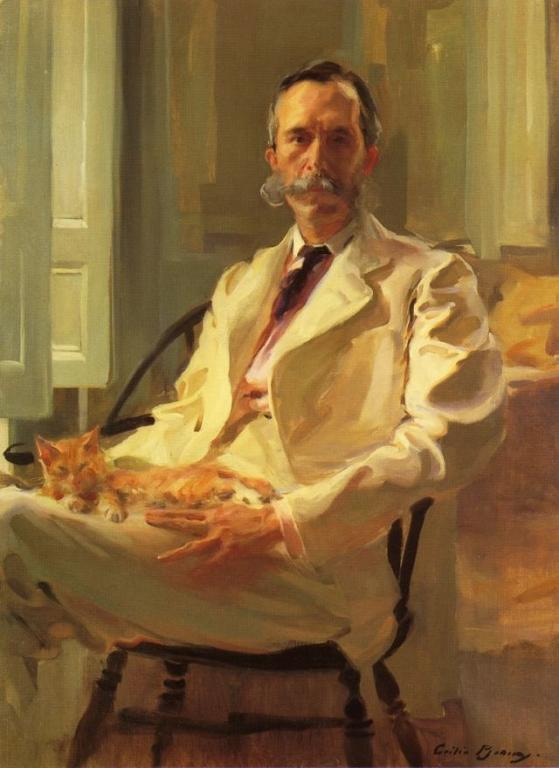

Henry Sturgis Drinker

by Cecilia Beaux

1898

The Case

The abbot Nanquan came upon the monastics of the eastern and western halls arguing about a cat. He took the cat and held it up with one hand while holding a knife in the other. He glared at the assembly and harshly said, “If you can give me a word, I will spare this cat. Otherwise, I will kill it.”

No one spoke. So, he cut the cat into two.

That evening Zhaozhou had returned to the monastery. Nanquan told him what had happened. Zhaozhou took off a sandle, put it on his head, and left.

Nanquan spoke into the empty hall, “If only you had been there. The cat would have lived.”

Gateless Gate 14

There are a handful of koans we find repeated over and over. Nanquan and the cat is one of those. It’s collected in all the great anthologies. It’s case 14 in the Gateless Gate, case 63, in the Blue Cliff Record, and case 9 in the Book of Equanimity. Dogen cites it in his personal collection of 300 greatest hits, as case 181. And the contemporary Korean master Seung Sahn counted it as the 9th of his 10 Gates, later 12 central koans in his koan teaching.

Of course there’s another thing about this case. Pretty much everyone is upset by it. The first time I heard it was as part of a dharma talk, where the teacher wanted to make sure we understand that Nanquan didn’t really kill the cat. Even though it says he killed the cat. Near as I can tell that’s a recurring theme addressed by many commentators starting from near the beginning of its being collected and commented on.

The case figures two stalwarts of koan literature. First is Nanquan Puyan, who lived from the middle of the eighth to near the middle of the ninth centuries. He was a successor to the great Mazu Daoyi. Which makes him a Dharma sibling to Baizhang Huaihai and Layman Pang, among other luminaries of the classic Zen way.

After his awakening and some further training, he settled in a hut he constructed on the slopes of Nanquan mountain. From which we get his name. Eventually Nanquan become the head of a large community a bit further down the slopes of the mountain In the Gateless Gate he appears in six koans. He had seventeen dharma heirs, the most famous of whom is Zhaozhou.

According to tradition Zhaozhou Congshen lived from the last quarter of the eighth century right through to the end of the ninth, at least according to tradition. Famously Zhaozhou didn’t begin formally teaching until he was eighty. And then he taught for forty years. Often he is called the greatest Zen master of the Tang dynasty. Zhaozhou features in seven koans collected in the Gateless Gate, including in the first case, which as you may recall features a dog.

As perhaps a footnote, while the case is told the same in the Gateless Gate, the Blue Cliff Record, and in Dogen’s collection; in the Book of Equanimity, the second half, the meeting between Nanquan and Zhaozhou is treated as a separate case. Although as a matter for formal koan practice, the two points the saving word followed by the cat’s death first, and then Zhaozhou and those shoes second.

I do appreciate those who say Nanquan couldn’t actually have killed a cat. However, I think holding a sharp knife and knowing death is involved is important. Similarly, I don’t entirely agree with those who say the koan is not about ethics. Even as I agree it is about the deepest matter. Still. Everything we do has consequences, and almost always real-world consequences. So, when a koan involves killing, that should not be ignored.

One of the first, probably the first book I read on Zen was Zen Flesh, Zen Bones. One of the first stories that caught my imagination in that book was among the “101 Zen Stories” collected by Nyogen Senzaki. Senzaki had selected and translated them from a thirteenth century Japanese koan anthology, the Shasekishū, the Collection of Stone and Sand.

It tells about a disciple of a dharma successor to Hakuin Ekaku. The student had been given the Sound of One Hand, Hakuin’s personal addition to the koan collection. However, after three years he couldn’t get a grip on it. He went to the teacher, Suiwo, and said he was giving up. Suiwo encouraged him to stay another week. Then another. And one after that. The student was in complete despair. Finally, Suiwo said, sit for three days “And if you don’t achieve awakening, then you should kill yourself.” The student had his awakening on the second day.

As they say there’s nothing like knowing you’re to be hung in two weeks to focus the mind. That knife has a place. So, remembering the cries of the cat and blood on the floor is important.

And, knowing koans are invitations into the deepest matters of our human hearts, and are best treated as life and death important. If we acknowledge their importance with full respect for the gravity of what they touch, then we can turn to the two invitations this case offers to us.

Here, as Daido Loori points out, in the last analysis “This koan is not about killing or not killing but, rather, about transformation.” If we allow the koan to be the universe rendered into a handful of words, and if we remember everything going on is about us, you and me, then invitations abound.

For one, the monks of the two halls fighting over that cat are not unlike our own minds. At least I can picture my mind in action, as a crowd of disreputable figures of several sorts arguing about a cat. That or knives and their uses. My brain can go on. And usually does.

Knives. Rich and terrible images. How words “cut like a knife.” Or, more positively how language can be a Swiss Army knife, in all its utility. I also think of Abraham’s holding that knife to Isaac’s throat. Or Solomon ordering that baby to be cut in two. There’s a Chinese proverb, sometimes incorrectly attributed to the Buddha that “the tongue is like a sharp knife, it kills without drawing blood.” And to round this bouquet of images out, there’s another Chinese proverb, popular in Buddhist circles in the Middle Ages, “lay down the killing knife and instantly turn into a Buddha.”

My brain, our brain. How like a knife. But also, it’s complicated, like the whole thing about killing that complicates the koan about awakening. Or does it? Despite the truths of the Buddhist proverb, we can’t actually silence our minds, not completely, not without, well, dying. But. There are ways of dancing with our thoughts, sharp though they may be.

I think of that story by the ancient Taoist sage Zhuangzi, about an enlightened butcher, Cook Ding. Burton Watson’s translation of the story has the cook telling his Lord.

“A good cook changes his knife once a year — because he cuts. A mediocre cook changes his knife once a month — because he hacks. I’ve had this knife of mine for nineteen years and I’ve cut up thousands of oxen with it, and yet the blade is as good as though it had just come from the grindstone. There are spaces between the joints, and the blade of the knife has really no thickness. If you insert what has no thickness into such spaces, then there’s plenty of room — more than enough for the blade to play about it. That’s why after nineteen years the blade of my knife is still as good as when it first came from the grindstone.”

Koans invite us to use our minds rather than simply be used by them. Here we’re invited into the place where we set down the killing knife. Not as some fake or dead silence. But the deeper place where the currents play, but against it all, the deep.

With that we can meet the killer. Nanquan. Or. Pehaps, you know, you or me. The killer holds the cat in one hand and a knife in the other. The blade captures a glint of light. Nanquan smiles. Is it friendly? Or is it something else?

So, what’s the cat? If we’re all the parts, we’re also the cat. What is the cat to us? Egyptian mythology has seeped into our hearts, and most of us know cats are divine creatures, if a bit on the bloody side. There is a persistent if sadly apocryphal story that Mohammed had a cat named Muezza and once when the cat was asleep on his sleeve, but it was time to get up to go to prayers that he cut the sleeve rather than disturb his cat.

Most commentators on the koan suggest we take the cat as our true boundless nature. If we don’t hold the idea too tightly. Sure. Words are sometimes traps. Usually they are. But sometimes something else.

And then that word. What’s the saving word? When words are mostly traps. When we’re lost in a sea of words? What then?

Where is the saving word?

In Zhuangzi’s story Cook Ding continues his master class with the Lord. “(W)henever I come to a complicated place, I size up the difficulties, tell myself to watch out and be careful, keep my eyes on what I’m doing, work very slowly, and move the knife with the greatest subtlety, until — flop! the whole thing comes apart like a clod of earth crumbling to the ground. I stand there holding the knife and look all around me, completely satisfied and reluctant to move on, and then I wipe off the knife and put it away.”

As they say: form and emptiness. But that’s just too vague.

There’s a dead cat. There’s blood on the floor. Your knife. Your cat. Your blood.

We have, perhaps, in that moment cut the one into two. The Empty has become the messy world.

And in at least one iteration of the koan that’s the end of the matter.

How do we lean into that? Our boundlessness and the great mess, all the mess, the bloody mess, are not two. First the koan showed how the empty is the great mess.

But even in that version, the matter of Zhaozhou and his shoes follows immediately. And in all the other versions, this meeting is critical to allowing the koan to take us home. Aitken Roshi in his comments says he was given to understand that in ancient China putting shoes on one’s head is a sign of mourning. I’ve been told master Seung Sahn says the same thing.

I have googled around and I’ve not found anything to confirm this. I like that idea. But the detail doesn’t really matter. Whether it’s a sign of mourning, or, more direct, a meeting of the moment, full, and unflenching. Open. Engaged. Not the moment before, when the cat died. But the moment now when he’s told about it. Then what? What’s your answer?

It reveals how the great mess becomes boundless.

How do we let grief and regret meet and mix into our lives? How do we meet the moments where they appear? And then allow the mystery to unfold? Adding in our part, as appropriate. Not too little. Not too much.

As the scripture says, you’re not it. But in truth it is you.

How are we present in and with and to the whole mess of our lives? Lives with choices. Lives with constraints.

Lives with consequences.

Old Nanquan holding up a cat and a knife. Zhaozhou putting his shoes on his head and walking out.

The world of forms rising and falling. The boundless.

Not two.