Indian stamp, 1991

Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar was born in Mhow, a town on the road between Mumbai and Agra, on the 14th of April, in 1891.

The 14th of April is celebrated in India, called Abedkar Jayanti (sometimes Bhim Jayanti) and Equality Day.

Known to those who admired him as Babasheb, “Respected Father,” B. R. Ambedkar was one of the singular figures of Twentieth century India. He served first as an advocate for civil rights. Then he was in leadership with the fledgling republic. And, last, as a religious leader.

In all these turns, he was a revolutionary.

He was born an untouchable.

However, his father was an officer in the British army, and this gave him access to an education.

Nonetheless, as an untouchable he was subjected to small and large indignities at school. These ranged from not being allowed to sit inside the classroom, to having to sit on a gunny sack he brought with him to and from school – so as not to contaminate the ground upon which he sat. He only had access to water at school because a paid servant was there to pour the water that the boy was not be allowed to touch – again because his very touch would contaminate it for everyone else.

These wounds marked his understanding of many things.

And. The boy was brilliant. He graduated from Bombay University, and then won a scholarship to Columbia, where he earned his first doctorate. From there he went on to earn a law degree and a second doctorate at the London School of Economics before turning his attention to what would become his life work.

In 1924 he established the Bahishkrit Hitkaraini Sabha, the Outcastes Welfare Association. Three years later he led a mass march at the Chowder Tank in Colaba, outside Bombay, demanding that untouchables have the right to draw water.

As civil rights leaders Dr Ambedkar and Mohandas Gandhi worked in an uneasy alliance. While Ambedkar was committed to independence, he had little trust of the dominant culture, and continued to press hard on behalf of the untouchable communities.

When Gandhi and others introduced the term “Harijans,” meaning “people of God,” for the untouchables, Amdedkar objected. He wanted the term “Dalit,” which was used in the sense to mean “outside the traditional castes.” Ambedkar opposed having some term like Harijan foisted upon them as one more example of being marginalized. He did quip that if his people were the children of God, then the upper casts would all be the children of monsters.

When India achieved independence, Dr Ambedkar was appointed India’s first law minister, basically India’s first attorney general. He was a central figure in composing the constitution, and specifically the parts outlawing discrimination against the Dalit community as well as other marginalized groups.

But, facing endless frustrations at his attempts to advance civil rights on behalf of all marginalized people, as a last straw, when his attempt to enshrine gender equality in laws concerning marriage and inheritance were frustrated, he resigned his office.

Instead Dr Ambedkar turned his attention to a new project.

For decades, feeling there was no place for him or the Dalit community within Hinduism, he had been on a spiritual quest. He explored the Sikh faith in depth. But eventually he settled on Buddhism as the best way for himself and his people. He embarked on serious study and out of that wrote several books outlining what he thought was the great contribution of Buddhism both to modernity, and for oppressed peoples.

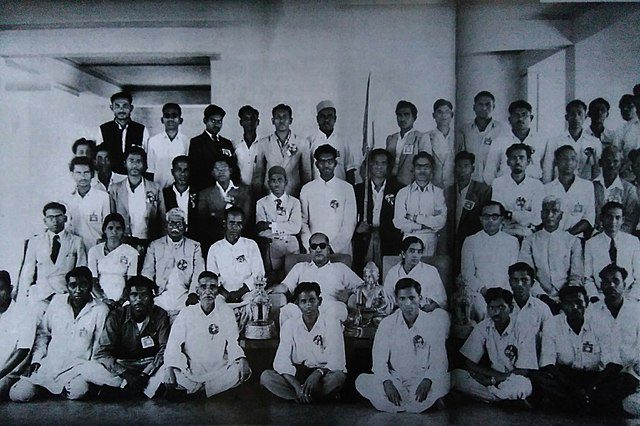

On the 14th of October in 1956 1956 Dr Ambedkar formally converted to Buddhism at a public ceremony. And immediately after his formal conversion, he led half a million Dalits present at that ceremony in their own conversions. (And. Yes, that was a half million people.)

The movement was based in twenty-two vows, giving the emergent tradition its distinctive flavor.

While his several books outlined his hope for Dalit Buddhism, or, as many call it, Ambedkar Buddhism, he died later in the same year of his formal conversion, and so the implementation of the new faith fell to others.

The Wikipedia article on Dalit Buddhism describes its distinctive features.

“Most Dalit Indian Buddhists espouse an eclectic version of Buddhism, primarily based on Theravada, but with additional influences from Mahayana and Vajrayana. On many subjects, they give Buddhism a distinctive interpretation. Of particular note is their emphasis on Shakyamuni Buddha as a political and social reformer, rather than simply a spiritual leader. They note that the Buddha required his monastic followers to ignore caste distinctions, and that he criticized the social inequality that existed in his own time. According to Ambedkar, a person’s unfortunate conditions are not only the result of karma or ignorance and craving, but do also result from ‘social exploitation and material poverty – the cruelty of others.’”

The same article cites the scholar Gail Omvedt who summarized the unique perspective of Dr Ambedkar’s Dalit Buddhism. “Ambedkar’s Buddhism seemingly differs from that of those who accepted by faith, who ‘go for refuge’ and accept the canon. This much is clear from its basis: it does not accept in totality the scriptures of the Theravada, the Mahayana, or the Vajrayana.”

Dr Omvedt then asks the question, “Is a fourth yana, a Navayana, a kind of modernistic Enlightenment version of the Dhamma really possible within the framework of Buddhism?” Given the existence of the movement, as well as other variations of modernist or rational Buddhisms in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, whether some other Buddhists might not like it, the answer obviously becomes yes.

Today the movement exists across India, although concentrated in Maharashtra and Uttar Pradesh, and counts the majority of Indian Buddhists, probably about five million people.

So, today it feels worthy to take a moment we might pause and consider him, his movement, and maybe how some variation of these reformed Buddhisms that embrace the deep consequences of Buddhist analysis might prove a healing balm for a troubled world.

Incense and many bows Babasheb!

Many bows!