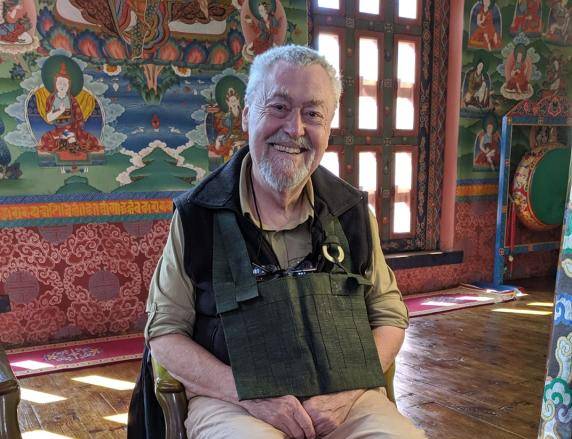

My friend Richard Kollmar observed that I have an interest in the Inklings and asked if I’d ever read George MacDonald. I had to admit I had not. He encouraged me to give the old Scot a try. He influenced a lot of that band of literary Christian intellectuals, especially C S Lewis and J R R Tolkien. And his influence extended beyond that flock, as well. G K Chesterton immediately comes to mind. Others include Lewis Carrol, WH Auden, and Madeleine L’Engle. He also touched in some degree Henry Longfellow, Walt Whitman, and Ralph Waldo Emerson.

After checking out the offerings, I selected MacDonald’s Phantastes. Perhaps inspired by what C S Lewis had to say about the book. “A few hours later I knew that I had crossed a great frontier.” “What it actually did to me was convert, even to baptize (that was where the Death came in) my imagination.”

It turned out to be a fortuitous choice.

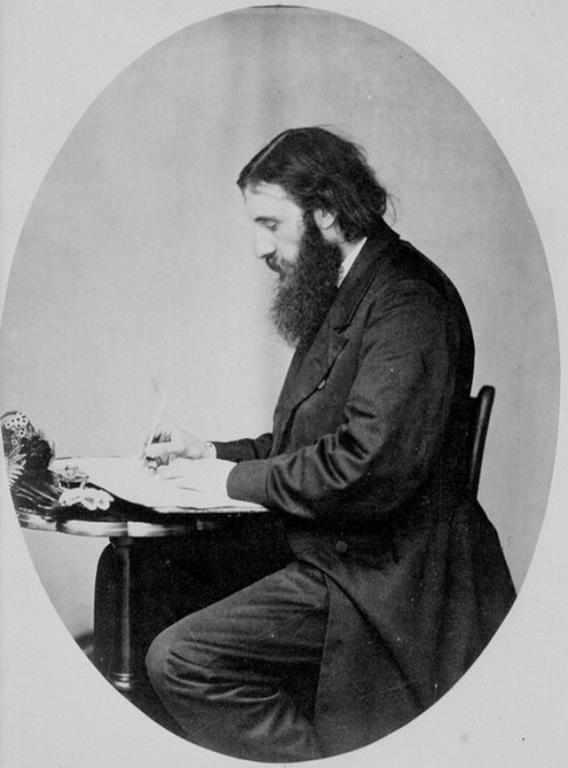

George MacDonald was born in Scotland in 1824. While farmers, the family was particularly literate, including Celtic and literary scholars among their number. His mother read multiple languages and his father had voracious intellectual interests. The house was littered with books. MacDonald’s health was fragile, he suffered over the years from asthma, and tuberculosis.

While he was raised in a Calvinist leaning Congregational church the family had multiple Christian connections ranging from Catholicism to the Scottish Episcopal Church. While he had an interest in pursuing medicine, he finally decided for ministry. MacDonald was ordained a Congregational minister in 1850. His universalist inclinations were not well received, and his salary was cut in half. Presumably encouraging him to consider other options. He half-heartedly tried a couple of other settlements, then taught at the University of London, did some editing, and finally turned to writing.

His first novel was published in 1863. And between writing and public lecture tours he was able to make a living. At 53 he was given a civil list pension upon the merits of his work. This allowed him to spend the next twenty years in Italy, writing. He returned to England in 1900, moving into a cottage his son Robert built for him. MacDonald died five years later, his ashes interred at the English cemetery in Bordighera, Italy, alongside his wife Louisa and his daughters Lila and Grace.

As noted, MacDonald was widely influential, especially touching Christian intellectuals. In addition to Lewis and Chesterton, MacDonald was a significant influence on J R R Tolkien. At least in his childhood and youth. People who investigate such things suggest influences stretching into the writing of the Hobbit. But at some point, Tolkien became critical of MacDonald as one observer noted, a preachy and didactic allegorist. Something Tolkien also felt about his friend Lewis, as well. Especially, I think, Lewis’ Narnia chronicles. But about which he said much less in public forums.

As to Phantastes. The plot, such as it is, has the protagonist, Anodos, which I read is Greek and means “pathless,” my favorite option, as it hints at a Zen usage we find in places like the great koan anthology, the Gateless Gate.

Not that MacDonald would have any familiarity with Buddhism, much less Zen. But other translations of “anodos” also work, “ascent” or the “way up.” Anyway, Anodos awakes in his room only to find himself now in Fairy land. He embarks on a quest which meanders through the world of Fairy. Through the quest he moves from an ego-centric experience of love as little different than lust to the discovery of a deeper, divine love.

While at this time in my life I have less patience for fantasy in general, I found Phantastes carrying me forward. I quickly had to let go of any desire for a coherent journey, and instead, let the picaresque nature of any authentic spiritual path, or perhaps pathless path, unfold. It certainly offered rewards to me for staying with it.

If I followed it correctly, Anodos starts out stary-eyed, but bound by his own desires, unable to really see beyond these constraints. Whether he takes off on the journey because of his dreams of something, or simply through the intervention of the mystery isn’t clear to me. But once embarked, through various experiences including being protected by others, he discovers a setting of himself, his ego and even his body, in a secondary place. Through this he increasingly finds how he is bound up with others. Near the end he comes to a complete surrender, into a type of death. Whether within the novel this is literal or figurate is not really clear to me. But from there, there is a resurrection into the person he will be going forward. Whether there will be further adventures is left open.

MacDonald opens a world of wonder. He engages imagination as the thread between our ordinary lives and the holy.

In Phantastes, MacDonald outlines the spiritual journey. He uses the Romantic spirit of his time, draws heavily on his Christian universalism, and as much on the traditions of fairy tales. I can both see why he isn’t so well known today, and why we would all be better off if he were.

For me one of the more intriguing elements McDonald introduces is the shadow. Despite being warned not to, Anodos opens a cabinet and a thing like a shadow but more than a physical shadow, or maybe less, it is a strange and unpleasant creature, appears and attaches itself to him. He struggles with it through a significant part of the story.

One of the more memorable images for me in the novel shows how Anodos and his shadow interact.

“Once, as I passed by a cottage, there came out a lovely fairy child, with two wondrous toys, one in each hand. The one was the tube through which the fairy-gifted poet looks when he beholds the same thing everywhere; the other that through which he looks when he combines into new forms of loveliness those images of beauty which his own choice has gathered from all regions wherein he has travelled. Round the child’s head was an aureole of emanating rays. As I looked at him in wonder and delight, round crept from behind me the something dark, and the child stood in my shadow. Straightway he was a commonplace boy, with a rough broad-brimmed straw hat, through which brim the sun shone from behind. The toys he carried were a multiplying-glass and a kaleidoscope. I sighed and departed.”

If unfolding wonder is the path that Anodos is following, his shadow is the opposite. The shadow is doubt, actually the worst sort of skepticism. It strangles wonder for a bare materialism. It stifles the imagination, the ways of wonder.

Robert Lee Wolff writes in his Golden Key how, “The shadow represents pessimistic and cynical disillusionment, the worldly wiseness that destroys beauty, childish and naïve pleasures, the delight of friendship and love; it is a foe of innocence, of openness, of optimism, of the imagination.”

I’ve not read the Golden Key (either MacDonald’s or Wolff’s), but in preparing for this reflection I’ve come across references and often criticisms of Robert Wolff’s apparent Freudian approach to Phantastes. I suspect people might be inclined to a Jungian or neo-Jungian read of MacDonald’s book. Me, I’m sympathetic. And we all read such texts through the eyes we have.

I’m kind of taken with the fact that MacDonald was born thirty-two years before Sigmund Freud and is in fact at exactly an age to be Freud’s father. And for that matter MacDonald was born fifty-one years before Jung, making him of an age to be Jung’s grandfather. MacDonald is solidly pre-psychoanalytic. And part of this is that in his spirituality shadow is something to be, if not suppressed, overcome, and then moved beyond.

For me at this point I mainly look at the world’s mystical writings, and I have little doubt that MacDonald is a mystic, that is he’s a pilgrim on the spiritual path seeking the deep wisdom, or probably in his language, God – hoping to find guidance on my own path. Challenges and invitations a bit more than judgments out of my perspective. When fortunate, quite a bit more.

I am at least latently also marked by a psychoanalytic, more Jungian than Freudian, sense. This perspective pervades our cultural assumptions. For me, for instance, the shadow is that which is hidden, and which needs to be met and integrated. For MacDonald, following an older tradition names the shadow as that part of a person which hinders one on the path, and which needs to be set aside, or overcome.

Me, of the many influences creating how I see the world, I am most informed by Zen. Here I find myself aware that through its history, Buddhism also finds doubt a great problem. Not unlike MacDonald’s shadow, which is a cruel skepticism, blinding one to wonder. In Zen, doubt is transformed. Baptized, if you will. It is no longer seen as an obstacle, but rather as a tool, or even a vehicle. Great doubt begats great faith which flowers as great awakening.

Of course, all of this needs to be met, and engaged.

What I find fascinating is the middle place between his ordinary ego-centric life and some form of ultimacy, which MacDonald calls Love. The arc of his journey is from selfish love to a transcendent Love. That middle place joing the two loves, the lesser and the greater, is found through imagination.

For me MacDonald’s imagination echoes my sense of Sambhogakaya in Mahayana Buddhism’s Trikaya. The Three bodies of Trikaya, Nirmanakaya, Dharmakaya, and Sambhogakaya invoke the wild and multidimensional quality of reality. This is not MacDonald’s world, but I find it maps nicely. And for me shows how the mystical of the world’s religions is rarely hard to reconcile.

Nirmanakaya being the world of history. In the novel represented by Anodos and the bookmarks of his life before and after the adventure. Dharmakaya in Buddhism is the vast openness, and for MacDonald, God. Or, Love.

In the Mahayana there’s also Sambogakaya, the realm of magic. I call it the third place. And, perhaps it’s MacDonald’s imagination. At least a variation on a theme. Another word for this place is wonder.

In my own life I’ve felt led more and more into this third place. The world of history is where we usually live. We are born, we age, and we die. In between lots and lots of things. Each of them appearing, engaging, and passing away. A great web of conditions and flow. All of it interconnected. And, behind, below, or, probably more precisely all the way through and at the same time, something. Or, in Zen, no thing. The wild open. The great empty. Perhaps in western terms at least some versions of God.

What caught me in this book was how he approaches the third place. In the novel McDonald showed the power of imagination. Magic. Dream. Wonder. Partially but by no means entirely in our hands. We have part of it, but mostly it is beyond our ken. We learn to play within it.

So. A lovely book. And a description of the way.

Check it out.

It might prove very helpful.