(Wikipedia)

There are people I try to remember on either their birthdays or the anniversaries of their deaths. People who have in some way touched the spiritual life. And out of that have brought some kind of healing to the world.

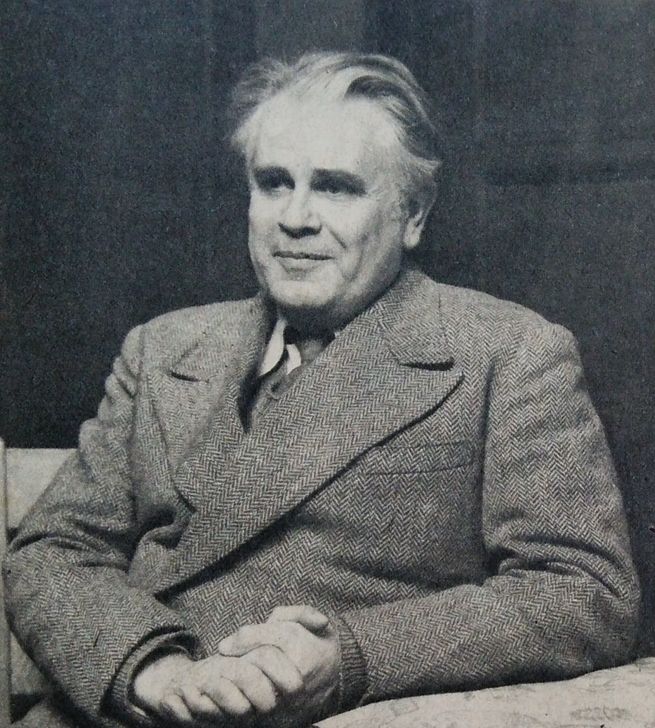

One such person is R H Blyth, who died on the 28th of October, in 1964.

Reginald Horace Blyth was born on the 3rd of December, in 1898. He was the only child of Henrietta and Horace Blyth, a railway clerk.

During the first world war Blyth was a pacifist and in 1916 he was sentenced to prison. When the war ended he attended the University of London, reading English and graduating with honors. While at university he met Anna Bercovitch and they married.

The young couple may or may not have lived for a time in India. But in 1925 he received an offer to teach at Keijo University, in Seoul, in Japanese occupied Korea. Already accomplished in several European languages, he immediately undertook the study of Chinese and Japanese. Blyth also began to study Zen under Zen master Hanayama Taigi at the Seoul branch of Myoshin-ji, a prominent Japanese Rinzai monastery. He also discovered D. T. Suzuki‘s Zen writings and devoured the literature.

He and Anna adopted a Korean child. And their marriage began to fall apart. They briefly returned to England together, but the marriage ended in divorce. He returned to Korea in 1936, and the next year he married a Japanese national, Kijima Tomiko.

The couple moved to Japan where Blyth began teaching at the Fourth Higher School, which later was renamed Kanazawa University. While he was seeking Japanese citizenship the war began and he was imprisoned as an enemy alien. During this time his first book, Zen in English Literature and Oriental Classics, was published.

The young Robert Aitken, who was also interred obtained a copy of this book from one of his guards and read it multiple times. He would later credit this as a critical step toward his becoming a Zen Buddhist. Later through prison transfers they spent part of the war in the same camp.

Aitken would later write of Zen in English Literature and Oriental Classics, “It was my ‘first book,’ the way Walden was the ‘first book’ for some of my friends, the way The Kingdom of God Is Within You was the ‘first book’ for Gandhi. Now when I look at it, even the type looks different, far smaller in size, and the references to Zen seem less profound. But it set my life on the course I still maintain, and I trace my orientation to culture – to literature, rhetoric, art, and music – to that single book.”

When the war ended Blyth worked in the transition, including co-authoring the Nigen Sengen, in which the emperor renounced claims to divinity.

In 1946 he was a professor at Gakushuin University as well as a private tutor for the crown prince Akihito.

His writings would be very influential on the first generation of Westerners who turned their hearts to Zen Buddhism. He was also very important in the introduction of haiku to English language readers. He published six book on haiku and two more on senryū. And seven books on Zen.

Blyth died on this day, the 28th of October, 1964. He was suffering from a brain tumor, but appears to have died from pneumonia.

Aitken Roshi wrote of him,

“Blyth Sensei often mentioned how as a boy he was inspired by Matthew Arnold’s ideal of developing one’s self to the fullest, to be one’s own best linguist, musician, artist, and scholar. Thus he learned Spanish in order to read Don Quixote, Italian to read Dante, German to read Goethe, and he made a valiant effort to learn Russian in order to read Dostoyevsky. And, of course, he was a deep student of Chinese, Korean, and Japanese.

“As a musician, he loved the oboe particularly but played virtually all the Western orchestral instruments. While he was at the Gakushuin, he constructed an organ, a remarkable feat of technical and musical skill. His words about Bach influenced my taste during the war and directed me on the path of music appreciation I still follow. And somehow just his passing words on Turner, Sesshu, and other artists established my understanding of art.

“There were flaws in this Renaissance man, however. He did not go far enough in his Zen practice to justify his confidence in commenting on the Mumonkan (The Gateless Barrier) and that book is probably the weakest of his works. He loved women and scorned them, his relations with those close to him were stormy, and his remarks about women, particularly in the essays he published after the war, infuriate readers and alienate them to this day.

“I accept these flaws as I accept the flaws in my own father. The one brought me into physical being and shaped my character, the other put me in touch with myself and with this rich, wonderful world. If we had not met, I might well have spent my life mundanely, saying and doing trivial things. His words rise in my mind as I speak to my own students, and his face still appears in my dreams.”

And so, thanks to our Western Zen ancestor, Reginald Horace Blyth, best known as R H Blyth.

Incense and bows…