(At our half day sit with Empty Moon Zen today, our guiding teacher Roshi Edward Sanshin Oberholtzer gave the dharma talk. He unveils the miracle promised in Dongshan’s Five Ranks, a promise which reconciles the absolute and relative, the essential and the contingent, form and emptiness. I asked if I could reprint it at my Monkey Mind blog and he graciously agreed. Well worth a read…)

In philosophy departments the pre-Socratics are often treated as precursors to the philosophical greats, Plato, Aristotle and on through a progression, from Hume to Kant, to Hegel, to Russell and others, culminating in the present day. But I prefer to see the Pre-Socratics as they are sometimes viewed in Classics departments, as shadowy representatives of a shamanistic past, the often irrational side of that Apollonian view of Greek civilization so treasured by our rational present. My favorite of these somewhat ghostly figures from a time at the dawn of letters, sages known only through scraps of quotes in later writers, my favorite is Heraclitus, who is remembered, if at all by the public and by Zen practitioners, for having prefigured Shunryu Suzuki’s famous one sentence summation of Buddhism “Everything changes”. Well over two and a half millennia before Suzuki, Heraclitus said “Panta Rei” – Everything flows.

But it’s not this seeming flirtation, accidental or otherwise, with a summation of the Dharma that interests me today. Rather it’s another of his statements, “hodos ano kato mia kai houtei” or, the road up down one and the same. I was reminded of this recently when going back to study again Dongshan’s Five Ranks. The Austrailian Zen teacher Ross Bolleter likes to group the Ranks together with the First and Second Ranks as a pair. We can easily see why that is so – the First Rank examining the particular within the essential, the second the essential within the particular; the road up, the road down, one and the same.

Dongshan’s poem for the first Rank runs:

Sho Chu Hen (J: the particular within the essential)

When the third watch begins, before the moon rises,

don’t think it strange to meet and not be conscious of meeting,

yet still somehow recall the beauty of ancient days.

The vast darkness of the night sky studded with twinkling stars, with the dust of planets, of asteroids, of meteors, with the occasional bat or owl flitting across the firmament overhead. The deep shadows of your house at midnight when, as you stumble out of bed, searching for the bathroom light, you stub your toe on that very particular, very solid coffee table lurking there in the darkness.

And our view, but only in our view and not in the road itself, our view of that upperward tending road now turns downwards as Dongshan himself turns from the particular within the essential to the essential within the particular, and to that sensation you have when, having stubbed your toe there in the dark, you find a whole world, a whole universe of sensation, of pain just there in what, up until a moment ago had been, perhaps, the most insignificant of body parts, your little toe, which now overwhelms you, which now consumes you in that vast all encompassing world of pain, the toe itself becoming a world which obliterates every other thought.

Dongshan’s illustrative poem, the poem that forms his second set of koanic points, goes:

2. Hen Chu Sho (J: the essential within the particular)

An old woman, oversleeping at daybreak, meets the ancient mirror,

so bright and clear, face to face, no special reality.

Stop searching for your head and don’t take shadows for reality.

Who among us hasn’t met that ancient mirror, perhaps at the end of stumbling through a darkened bedroom late at night after stubbing our toe on misplaced and mysterious furniture strewn there in the dark by some malefactor, probably you yourself. Or perhaps just at dawn like the old woman, standing before that mirror, cracked and dust ridden or fogged with the morning shower’s steam but still, revealing there through its particularity, through its very thusness, the absolute in all its bright clarity. You are not it, but in truth, it is you.

And Dongshan continues with an echo of that old Halloween tale of the headless horseman galloping along the roadways of the Hudson Valley in Washington Irving’s retelling, searching for his head in among the shadows of Sleepy Hollow. It’s enough, for us at least, to reach up our hands and grasp the head that was there all along, heeding Dongshan’s admonition to stop searching for your head and not take shadows for reality.

We might replace Dongshan’s poem with one a bit more current, if only a couple of centuries old. William Blake’s Auguries of Innocence begins, of course, with four lines that easily evoke the essential within the particular.

To see a World in a Grain of Sand

And a Heaven in a Wild Flower

Hold Infinity in the palm of your hand

And Eternity in an hour

But we needn’t turn to nature, to the sand stewn beaches or the flower bedecked meadows. Open your eyes and look into another’s face. There, in that single instance, in that one moment of the actual, you’ll find all of the Dharma, all of creation, a universe of pain, of joy, of wonder; heaven, yes; infinity, yes; eternity, yes; but also the simple, the mundane, the everyday, a universe of the everyday, an eternity of the simple. As we walk down the sidewalk, each person we meet, each person we nod to, each person we smile at, even, perhaps especially, each person we ignore and don’t see, each has a life as complex, as full, as astounding as our own. Each an instantiation of the particular, each blooming forth a whole world, there if we could just see it. Each the absolute within the particular.

As we travel down Dongshan’s road, we sense the intimacy that comes with this interplay of the essential and the contingent, the absolute and the particular. The Buddha stepping forth from beneath the Bodhi tree and announcing that “Today, I and all beings are awakened together”, is the same movement that sees the sadness in the face of the Virgin Mary holding her dead son in Michelangelo’s Pieta, the same recognition one sees in the grief of Emmit Till’s mother standing with his casket, refusing to let the world turn away from what it had done to her child, the same hope we find in a young family making it to the other shore of the Rio Grande, the same joy in the face of a friend finding a long lost friend. Today, you and I and all beings feel that sadness, that grief, that hope, that joy.

As we travel down Dongshan’s road the very pebbles, the puddles, the cracks and crevices blossom forth with potential, each containing the whole of creation, the vast mystery. A nineteenth century English clergyman walking the cliffs of Dover and finding, there in a fossilized crustacean just lying out there on the beach, a whole new world. A squirrel, rummaging through the grass in my backyard, finding a treasure of hidden acorns. A child gazing up at the night sky in wonder finds in that moon, in those stars, all of the universe, the great unknown. And we hear this in Eugene Field’s children’s poem, which I hope you’ll forgive a grandfather for reciting:

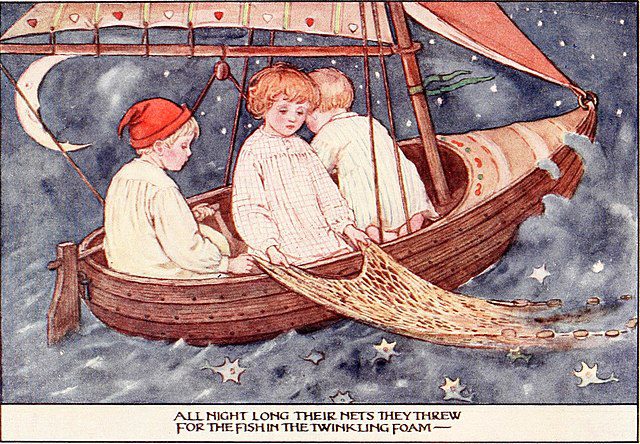

Wynken, Blynken, and Nod one night

sailed off in a wooden shoe —

Sailed on a river of crystal light,

into a sea of dew.

“Where are you going, and what do you wish?”

the old moon asked the three.

“We have come to fish for the herring fish

that live in this beautiful sea;

Nets of silver and gold have we!”

said Wynken, Blynken, and Nod.

I can’t help but call to mind the net of Indra, cast into that sea of dew, each cross link knotted and bejeweled with a crystal whose facets reflect all of the other jewels and all of the rest, the river of light, the sea of dew, the old moon, the herring swimming in that sea.

The old moon laughed and sang a song,

as they rocked in the wooden shoe,

And the wind that sped them all night long

ruffled the waves of dew.

The little stars were the herring fish

that lived in that beautiful sea —

“Now cast your nets wherever you wish —

never afraid are we”;

So cried the stars to the fishermen three:

Wynken, Blynken, and Nod.

That old moon, risen after the third watch now, for what child hasn’t woken up in the middle of the night, who among us has not stirred before or after the third watch, stumbling through the dark, fumbling for the light switch, encountering the particularity of that coffee table, perhaps even more acutely the particularity of that lego brick painfully and amusedly under foot. Just this, just this.

But the children are not yet done:

All night long their nets they threw

to the stars in the twinkling foam —

Then down from the skies came the wooden shoe,

bringing the fishermen home;

‘Twas all so pretty a sail, it seemed

as if it could not be,

And some folks thought ’twas a dream they’d dreamed

of sailing that beautiful sea —

But I shall name you the fishermen three:

Wynken, Blynken, and Nod.

And here, here is the particularity out of which the universal arises:

Wynken and Blynken are two little eyes,

and Nod is a little head,

And the wooden shoe that sailed the skies

is a wee one’s trundle-bed.

So shut your eyes while Mother sings

of wonderful sights that be,

And you shall see the beautiful things

as you rock in the misty sea,

Where the old shoe rocked the fishermen three:

Wynken, Blynken, and Nod.

But here’s the miracle promised in Dongshan’s Five Ranks, a promise which reconciles the absolute and relative, the essential and the contingent, form and emptiness. Deep within the particularity of those two little eyes, of that little head, lies that growing child, the Dharmic being given birth to on those misty seas. We have all been there. We all come from there. Whether the road we take goes up or down, this reconciliation is here, in each of us, in each of you, nothing special and yet so very precious.

As that old woman found,

“So bright and clear, face to face, no special reality.”