Keiji Nishitani died on the 24th of November, in 1990.

I mean to mark this day as it rolls around and take advantage of it to remind those who knew of his work, and to introduce him to those who were unfamiliar with this remarkable person and the “school” with which he is closely associated. I’m sorry I’ve not been quite as faithful to this intention as I could or should be. But, at least this year, I’ve caught the day as it has arrived.

I continue to edit, cut, and expand this small introduction.

If you have any interest in Zen and you’re unfamiliar with Professor Nishitani, this might be a real treat.

He was one of the principal figures in the establishment of the Kyoto School, which the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, tells us was “a group of 20th century Japanese thinkers who developed original philosophies by creatively drawing on the intellectual and spiritual traditions of East Asia, those of Mahāyāna Buddhism in particular, as well as on the methods and content of Western philosophy.”

I would add about the Kyoto School it is of particular importance to those of us concerned with Zen as a living spiritual tradition. As a child of the West who has found Zen to be central to my spiritual life, the school has been incredibly helpful for me in bridging the different approaches of east and west.

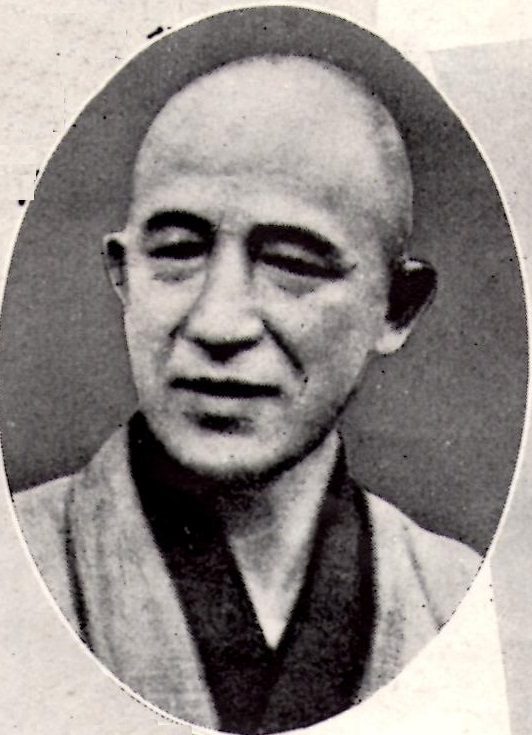

Nishitani was born in a small town on the Japan Sea on the 27th of February, 1900.

While brilliant he failed to win entrance to the prestigious Daiichi High School because of tuberculosis, the disease which killed his father when he was fourteen. At seventeen he retook the examinations, again proved to be brilliant, but also passed the physical examination.

In High School he became fascinated with Zen, principally through the writings of D.T. Suzuki. He also wandered from the established curriculum reading Dostoevsky, Nietzsche, Emerson, the Bible as well as a life of St Francis. Critically, he stumbled upon a book by Kitaro Nishida. Nishida was a professor at the Kyoto University, and the founder of the Kyoto School. When he graduated he entered Kyoto University in order to study with Nishida.

Upon graduation he became a professor at Otani University in Kyoto, and then later, at Kyoto University. He also began Zen studies as a householder with Gyodo Furukawa, master at Engakuji. He then continued with Taiko Yamazaki at Shokokuji. Nishitani would continue with his Zen teacher for twenty-four years. I’ve found it critical that while a working philosopher he remained constantly grounded in the actual disciplines of the Zen way.

Obtaining a fellowship he spent for two years at the University of Freiburg where he studied with Martin Heidegger. There Nishitani became fascinated with Germany’s mystical traditions, delving especially into Meister Eckhart’s work, as well as taking a deep dive into the writings of Friedrich Nietzsche.

After this he returned to Japan where he earned his doctorate.

During the war Nishitani and the Kyoto school writ large embraced a vision of Japanese imperialism. Most of what we know turns on a series of discussion sponsored by the journal Chūōkōron. In the The Cambridge History of Japan, Tetsuo Najita and H. D. Harootunian wrote of Nishitani and his fellow academics from Kyoto:

The group’s “central purpose was to construct what they called a “philosophy of world history” that could both account for Japan’s current position and disclose the course of future action. But a closer examination of this “philosophy of world history” reveals a thinly disguised justification, written in the language of Hegelian metaphysics, for Japanese aggression and continuing imperialism. In prewar Japan, no group helped defend the state more consistently and enthusiastically than did the philosophers of the Kyoto faction, and none came closer than they did to defining the philosophic contours of Japanese fascism.”

What all actually has been said and what it has meant has generated a great deal of ink in the postwar years.

And, largely as a consequence at the end of the war Nishitani was deemed “unsuitable” for teaching by the occupation forces. For me of additional interest is how during this time he intensified his Zen practice as well as turned to writing. It was also at this time he dove deeply into the questions of nihilism and a Zen response to it.

Five years later he was reinstated to his teaching post. At this time Nishitani’s magnum opus, published in 1983 in English as Religion and Nothingness was published. In his retirement he accepted the position of chief editor of the Eastern Buddhist, a periodical founded by D.T. Suzuki, which became a fountain of insight into aspects of Buddhism and Zen from a scholarly perspective.

In this fruitful post-war period Nishitani became the generally recognized successor to Kitaro Nishida as leader of the Kyoto School.

James Heisig writes of him, “As a person, Nishitani is remembered by those who knew him as magnanimous but possessed of an inner strength and an uncanny ability to strike at the heart of the matter in discussion. Ueda Shizuteru recalls after nearly forty-five years in his presence, ‘It was almost as if he were breathing a different air from those around him.’ Mutõ Kazuo, known as one of the major disciples of Tanabe, called him ‘the finest, most remarkable teacher I have ever encountered upon this earth.'”

The unsigned article about Nishitani at Wikipedia notes “In works such as Religion and Nothingness, Nishitani focuses on the Buddhist term Śūnyatā (emptiness/nothingness) and its relation to Western nihilism. To contrast with the Western idea of nihility as the absence of meaning Nishitani’s Śūnyatā relates to the acceptance of anatta, one of the three Right Understandings in the Noble Eightfold Path and the rejection of the ego in order to recognize the Pratītyasamutpāda, to be one with everything.

“Stating: ‘All things that are in the world are linked together, one way or the other. Not a single thing comes into being without some relationship to every other thing.’ However, Nishitani always wrote and understood himself as a philosopher akin in spirit to Nishida insofar as the teacher—always bent upon fundamental problems of ordinary life—sought to revive a path of life walked already by ancient predecessors, most notably in the Zen tradition.”

A complex figure. A profound intellectual. Tarnished and burnished.

And for me, a teacher of consequence.