Last year I noticed that today, the 16th of September, 1885, was the birthday of the noted Neo-Freudian psychoanalyst Karen Horney. I riffed a bit on her and her connections to Zen Buddhism, and how significant it was. I looked and thought I’d like to tweak it slightly, and share that here.

Horney was one of a relatively small band of psychoanalysts and psychologists who would take their original inspiration and often direct instruction from Sigmund Freud and then push on. Horney is the founder of a feminist psychology that has been a critical corrective to the domination of psychological theory from a near solely masculine perspective.

And, then, there’s the Zen thing. For me noting her birthday triggers a cascade of thoughts about the meeting of Western psychology and Zen Buddhism.

A lot of this turns on D. T. Suzuki, the person who along with his popularizer, Alan Watts, first really brought the West’s attention to Zen. Over the years there has been a lot of criticism of Suzuki, his unacknowledged sectarian biases as well as his focus on an a-historical encounter with enlightenment, awakening, and in more recent times noting his alignment with Japanese nationalism during the Second world war. The critique of that focus on awakening divorced from most of the rest of Zen Buddhism’s teachings and practices continue with Alan Watts. On the other hand it was precisely his focus on enlightenment that made Zen so tantalizing for my generation and which opened the doors to Zen becoming a part of Western culture. So, a mixed bag.

As it relates to Horney, when she lived in Manhattan she met Suzuki and formed a friendship. While I can’t find any evidence she practiced Zen in the sense we might understand that term today, there is little doubt her interest in Zen was central to her developing ideas of a “real self.” As a small coda shortly before her untimely death from cancer she traveled with D. T. Suzuki to Japan and toured many Zen monasteries. Its hard not to indulge the great “what if,” what if she’d lived a few decades after this experience, and even, maybe, taken up the disciplines of Zen?

As Buddhism has traveled from one culture to another it has always engaged in a dialog with indigenous religions and culture. For me the most dramatic of these encounters was the move to China and out of that the birthing of Zen. And so, of course, there is today a rich encounter between Buddhism and Christianity, as well as lesser but important conversations between Buddhism and Judaism and Islam. But here in the modern West the encounter that has captured most imaginations has been between Buddhism and Zen and psychology. Perhaps not so surprising in a largely secular age with its interest in the person separated from the conventions of religion – and then encountering a religion with an ancient and sophisticated psychological model, really models.

Karen Horney is an important part of the beginnings of that conversation. A conversation that continues to broaden and deepen to this day, and we can see as we look around, is very much a continuing thing. The possible depths of this dialog nowhere near plummeted.

So, just a pause on that journey to acknowledge and celebrate one of its founders.

Thank you, Karen!

Endless bows.

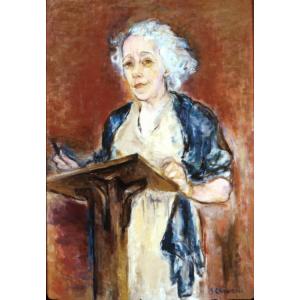

(The painting displayed here is by Suzanne Carvallo Schulein and hangs in the National Portrait Gallery at the Smithsonian Institution)