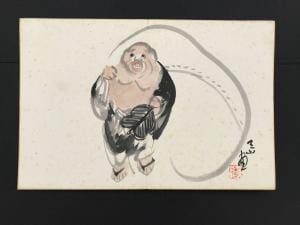

The Fat Man and the Ox

What do these two images have to do with anything? The answer: everything. They illustrate means and ends in a forceful way. Their source is the famous Zen parable of the Ten Ox-herding Pictures, which I consider the key to understanding just about everything I think I know about birth, life, death and what they actually may mean. The fat jolly man who appears at the end of the parable and takes the place of the little ox-herder in the first part of the story, is actually the fully realized little boy and ox transformed.

He is known in Chinese as Budai 布袋 (J. Hotei), who is both the Cloth Bag (as his name suggests) as well as the historical Buddha 佛 (C. Fo, J. Butsu or Hotoke); in other words, he is the Wise Man of the Shakya Clan in India, Shakyamuni, the 6th-century-B.C. founder of Buddhism. In either of these guises he is always shown laughing, whether seated in temples as the principle giant Buddha on the altar, or in restaurants near the cash register where customers are encouraged to rub his tummy for good luck. As Cloth Bag in the marketplace, he brings all beings into the laughter and joy of existence through a single profound teaching about truth.

“There are not two dharmas, or truths, only one,” he says. The ox the young boy controlled until it disappeared, leaving him seemingly alone, was merely a part of himself that he had not yet discovered. Once he woke up to the reality of things, he realized his error. Nothing was lost. Thinking he had lost that part of himself was as foolish as mistaking the animal traps and fishhooks that hunters and fishermen use for what they cannot get by themselves. Without the ox, no longer controlled by the ring in its nose and rope in the boy’s hand, none of the work he and the ox accomplished together, would get done.

While the means most certainly are not the end, they also are not separate from it. What takes us to an awakening is part of the awakening itself. In the seventh of the ten ox-herding pictures we see the young oxherd honoring the memory of something that provided what he needed to reach the true self. He seems to be welcoming the new day and waving best wishes to an absent ox. In short order, the self he presumed himself to be, will disappear as well. As the last ox-herding pictures show, we will see not a boy, or an ox, or anything in the world, other than a smiling old fat man in the marketplace, playing with children and sharing with them the stuff in his big cloth bag, a kind of Santa without a discriminating bone in his body.

This parable warns me that whatever I see as the ultimate goal in life – whether that is enlightenment, salvation, or nothing I can imagine –cannot be reached until I appreciate the people, circumstances, and practices that can get me there. I am literally not alone. Not even when I think I am. My ox, I see now, is everyone. That includes my parents, my teachers, students and friends, and above all, my wife and sons.

But it is also my enemies, or just people I think I have nothing in common with. My ox is also what I’ve learned and haven’t learned, what I believe and what I don’t. In equally personal terms, my ox is the practice of prayer, of meditation, and the indignant dismissal of all that stuff. And my ox most definitely is all the music and art that brings sounds and sights from the human heart —

It’s all in the bag the fat man carries everywhere.