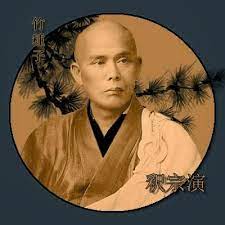

The Japanese Zen master Soyen Shaku died on this day, the 29th of October, in 1919.

I offer some incense. And thoughts follow like those bubbles on a stream…

Soyen Shaku was a prominent Rinzai master, of enormous importance to us who practice Zen in North America, and, really, the West writ large. I wrote about him in my study of Zen come to North America, Zen Master Who?

Our common ancestor in the foundation of Western and particularly American Zen is without a doubt Soyen Shaku.

He was born in 1856. He spent three years at Keio University, which was highly unusual for a Zen priest at that time. Also, the university had a fascinating connection to Western and especially Unitarian liberalisms, and I’m much taken with that intertwining of East and West at the beginning of Zen’s reach to us.

This was the first of his many experiences outside the norms of Japanese priesthood. An adventurous young man, he traveled to Ceylon to study Theravadan monasticism—possibly the first Japanese priest to do so.

In 1880, he was named a Dharma successor to Imagita Kosen, abbot of the prominent Rinzai training monastery Engakuji, in Kamakura, and became master of Engakuji when his teacher died.

When he received an invitation to speak at the World Parliament of Religions in Chicago in 1893, most of Soyen Roshi’s associates, priests, students, and prominent laypeople discouraged him from attending. America was, after all, uncivilized and unspeakably barbaric. They were dirty and violent people. But he was adventurous and asked one of his lay students who spoke English, D.T. Suzuki, to draft his letter of acceptance.

In Chicago he encountered Paul Carus, a compelling figure who, through his writings and publishing ventures, was important in developing a Buddhist presence among North Americans of European descent. Theirs proved to be a fruitful friendship. In 1905, Soyen Roshi returned to the United States at the invitation of Alexander Russell, staying in San Francisco for about nine months. This was the extent of Soyen Shaku’s direct connection to North America.

But over the next few years, several of his students came West. And they would help to shape Zen for Westerners seeking pointers and guidance on the intimate way.

Now, there were people of the Zen way who arrived in the United States before the World Parliament, but their names remain unknown. The Soto missionary Hosen Isobe, who is sometimes overlooked, but whose importance to the Zen project in the West, wouldn’t establish the first Zen temples in North America until three years after the Rinzai master’s death.

Soyen Shaku gave the first talk by a Zen master in the West that we have a record of. His talk at the Parliament avoided technical terminology. But, also, cut to the heart of much of the spiritual dilemma. It’s worth a read.

While at the conference he met the philosopher and student of world religions, Paul Carus. Carus was impressed with his talk, and asked that he stay to help provide translations and other writings regarding Zen Buddhism for Open Court Publishing. The Roshi declined, but he promised to send someone. Actually two of his disciples would end up in America. One was the itinerant Zen priest Nyogen Senzaki. The other was a lay disciple, the scholar D. T. Suzuki. Through Suzuki’s voluminous work and later through the popularizations of his writings by Alan Watts, Zen began to have a place in the Western imagination.

Also of note, Sokei-an Sasaki, a successor to one of his successors was one of the first Zen teachers to come to the West to stay. Commenting on this my friend the old dharma hand Stephen Slottow adds, “Gary Snyder pointed out that Soyen Shaku’s line had far more involvement in the West than any other Rinzai line, at least for a long time. His major heir was Sokatsu Shaku, the teacher of Sokei-an and Goto Zuigan, who were both teachers of Ruth Fuller Sasaki. Snyder went to Japan under the auspices of RF Sasaki’s Zen institute and studied with Sesso Oda, Goto Zuigan’s successor. Soko Morinaga (Daishuin West) was the heir of Sesso Oda. Other Rinzai lines have become important in the West more recently, but the history of Rinzai Zen in America is intimately bound up with Soyen Shaku’s line.”

Soyen Shaku also contributed to the early writings in English with his Sermons of a Buddhist Abbot, published by Open Court in 1906, and later issued as Zen for Americans.

Here is chapter 11, his “Reply to a Christian Critic.”

Endless bows…