For anyone familiar with the origin of the holiday, the fact that Guy Fawkes has become an anarchist meme is truly hilarious. For anyone who’s not, here’s the skinny.

The Gunpowder Plot

In 1605, England had been Protestant for a couple of generations, but with persistent (and, in some places, very prominent) Catholic minorities. Some people believed England could still be restored to communion with Rome by force of law, if a Catholic monarch could only be installed. The Act of Supremacy made the monarch head of the Church of England, after all.

Guy Fawkes became a Catholic some time in his youth, and served as a mercenary for Spain in the Eighty Years’ War. He joined a conspiracy that planned to blow up Parliament, assassinate King James I, and place his daughter Elizabeth (whom they would then rear as a Catholic) on the throne. They rented some rooms underneath the Houses of Parliament, filled them with barrels of gunpowder, and set Fawkes to stand guard.

However, some of those prominent Catholic minorities were in fact members of Parliament. Some member of the plot sent a letter to Lord Monteagle, a Catholic baron, warning him to avoid entering the House of Lords on the relevant day. Lord Monteagle showed the letter to the king, and from there, the plot unraveled on November 5th. The government executed Fawkes and several other conspirators, and November 5th became a national day of thanksgiving, marked by bonfires—thus known as either Bonfire Night or Guy Fawkes Day.

I Love the Smell of Napalm in the Morning

To us, this story is little more than fun historical lore. There’s no more risk of anyone trying to install a Catholic monarch in the US today than there is of a genuine anarchist revolution. But the definite right-wing turn of a lot of politics in both Europe and the Americas over the last decade or so does have ties to Catholicism, and this bears examination.

There are a few reasons for this, historically. Authoritarianism, especially fascism, clearly attracts a certain type of Catholic in every age. I don’t think this is inevitable, but it is natural; believing in angelic and clerical hierarchies makes it emotionally easy to believe in rigid civil hierarchies too, regardless of whether or not they actually have anything to do with each other logically. And even apart from any question of sincere (however emotionally-driven) belief, religion is a great excuse to be an officious busybody, a type which thrives in authoritarian systems and which those systems tend to reward.

Then there’s the æsthetic side of politics, something fascists have always been good at. That too blends very well with Catholic pageantry, especially since—while non-European traditions of Catholicism have always existed in Asia and Africa, and have come into existence among the indigenous peoples of North and South America—Catholicism is strongly associated with white1 Europeans in most people’s minds. The way the Church adopted the language and symbolism of Rome, up to and including their gods, again makes it easy to think of this as one romantic dynasty. Fascism plays that for all it’s worth to win the allegiance of Christians—not because they have any interest in Christianity, but because our religion is still big enough to form a locus of political, cultural, and economic power.

Playing With Matches

What, then, is the Catholic response here? Obviously there are as many answers to this as there are Catholics, but there are two I’m interested in: the integralist response, and one other.

Integralism is a school of Catholic political thought, currently associated with a handful of intellectuals such as Adrian Vermeule and Sohrab Ahmari. There are a few different versions of it; they tend to share a rejection of liberalism and a corresponding suspicion of values like autonomy and liberty. Many endorse a robust welfare state, and there are even left-wing forms of integralism. Most integralists advocate a strong, centralized, explicitly Catholic state—whether non-Catholics will enjoy freedom of worship in this state is a little less explicit, but they broadly agree that it is the state’s responsibility to promote Catholicism and to, let us say, incentivize conversion.

Many principal figures in the movement have, predictably, associated themselves with fascists abroad and with Trumpism here in the States. I personally doubt this has much to do with an actual enthusiasm for Trump, and is probably inspired by a desire to use that movement as a stepping-stone to power. The issue here—apart from the fact that a cynical alliance with fascists is, both spiritually and practically, just as bad as if not worse than a sincere alliance with fascists—is that it’s not going to work. What it is going to do is corrupt the faith and morals of a great many Catholics; and indeed, it has done already.

This is particularly noticeable with the issue of anti-Semitism, a persistent disease in Catholic circles and a key element in most forms of fascism. The discourse on Twitter dot gov had two nauseating eruptions in just the last week: one a renewed apologia for the disgusting conduct of Pope Pius IX in the Mortara affair, the other a placid reflection from an Austrian monk that placing the Jews in ghettoes was “mostly counterproductive” but apparently not wrong in principle.

I have said before, and I expect I will say again, that anyone who mistreats the Jewish people commits sacrilege against God and the Mother of God. And yes, things like kidnapping their children or segregating them from the rest of the community constitute mistreatment. It is a burning shame to the whole Catholic Church that we even need to have this conversation—and need to have it less than a century after the worst assault on the Jewish people in recorded history.

Smoke on the Mountain

Yet even this, while a disgrace, is not the root issue with integralism (though it may be integralism’s most poisonous flower). Partly as an ex-Protestant, I’m not really here for the doctrine of the perspicuity of Scripture; some parts of the Bible are very opaque, even if you have had a historical and literary education. But I would have thought that the moral lesson of this passage was unmistakable:

Again, the devil taketh him up into an exceeding high mountain, and sheweth him all the kingdoms of the world, and the glory of them; and saith unto him, “All these things will I give thee, if thou wilt fall down and worship me.” Then saith Jesus unto him, “Get thee hence, Satan: for it is written, Thou shalt worship the Lord thy God, and him only shalt thou serve.” —Matthew 4.8-10

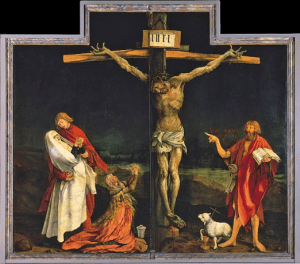

The response of Jesus is not like the integralist response. Christ did not come to assume terrestrial power; when he does do that, it’s the end of the world. That kind of power, like “riches and the cares of this world,” is a temptation. The parable of the wheat and the tares is precisely about Christ not assigning angels the duty of rooting evil out of the Church by angelic means—how much less, then, should the Church be trying to root evil out of the world by worldly means? This was not laid down for us by our Lord, either by precept or by example, with a few ambiguous exceptions like the cleansing of the Temple; and even that was about correcting an abuse enacted by religious people, not about compelling pagans to enter the Temple.

When I was a bitter, edgy teenager, I used to welcome the idea that there was a persecution against Christians on the horizon in this country. I no longer think any such persecution is remotely likely; but I’m coming back around to the idea that it might do us a great deal more good than harm. Trying to acquire, or to maintain, Catholic power and prestige has absolutely nothing to do with the Gospel. The Gospel is about going to the cross, and the resurrection that takes place afterwards comes from God, not Caesar, and still less ourselves.

1Or, at most, swarthy, when we come to Spain and southern Italy.